The humanitarian impact of de facto settlement expansion: The case of Elon Moreh

New research to improve humanitarian response and preparedness

The establishment and continuous expansion of settlements, in contravention of international law, is a key driver of humanitarian vulnerability.[19] It has resulted in Palestinians being deprived of their property and sources of livelihood, restricted access to services and has given rise to a range of protection threats that trigger demand for assistance from the humanitarian community.

Research and the monitoring of settlement expansion has focused on the construction of residential areas and has neglected other means of expansion such as road networks and the development of agricultural and tourist sites, mostly on privately owned Palestinian land without formal permits, but with the acquiescence of the Israeli authorities (hereafter de facto expansion). Additionally, while issues such as settler violence and access restrictions to protect settlements are regularly monitored, their relationship to the phenomenon of settlement expansion is often overlooked.

To enhance the humanitarian community’s understanding of these patterns and its ability to respond, OCHA has collected and analyzed data on several affected areas in the West Bank.[20] The following case study of Elon Moreh settlement in the Nablus governorate is the third in a series of Humanitarian Bulletin articles on the findings of this research.[21]

Background

Elon Moreh settlement (currently some 1,800 residents) was established in 1979 next to Rujeib village (Nablus), on privately-owned Palestinian land requisitioned by the army for citing military purposes. Following a petition by the landowners, the Israeli High Court of Justice (HCJ) ruled the requisition unlawful under international humanitarian law (IHL) and ordered the evacuation of the land and its return to the Palestinian owners.[22] A few months later, the settlement was relocated to a nearby site registered as “state land”, where it stands through the present.

Elon Moreh settlement (currently some 1,800 residents) was established in 1979 next to Rujeib village (Nablus), on privately-owned Palestinian land requisitioned by the army for citing military purposes. Following a petition by the landowners, the Israeli High Court of Justice (HCJ) ruled the requisition unlawful under international humanitarian law (IHL) and ordered the evacuation of the land and its return to the Palestinian owners.[22] A few months later, the settlement was relocated to a nearby site registered as “state land”, where it stands through the present.

While the relocation of the settlement was prompted by an IHL provision protecting private property during military occupation, Elon Moreh subsequently became an emblematic case of de facto expansion on private Palestinian land.

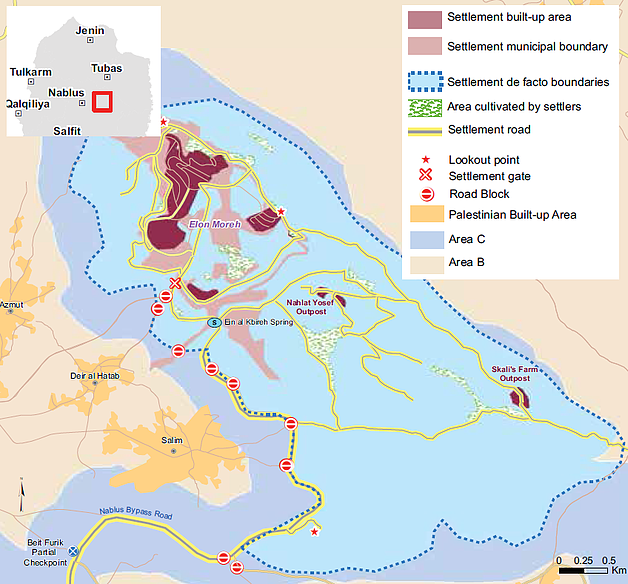

Although the official municipal boundaries of Elon Moreh are declared by the Israeli authorities to be 1,844 dunums,[23] OCHA’s research found that the area of land controlled by the settlement and where Palestinian access is severely restricted or impossible is more than eight times larger, i.e approximately 15,500 dunums.[24] According to official Israeli records, 63 per cent of the land within this area is privately-owned by Palestinians from three nearby Palestinian villages: Azmut, Deir al Hatab and Salem, with a combined population of 11,500. [25]

Elon Moreh settlement: official and de facto boundaries

Expanding a permanent settler presence

While the majority of the land within the settlement-controlled area remains undeveloped, Elon Moreh settlers have gradually expanded their presence on it. The first wave of de facto expansion took place during the 1990s and primarily entailed residential building. By 2000, the settlement’s built-up area was 40 per cent larger than its official boundaries. In the following years, two residential outposts (“Skali Farm” and “Nahlat Yosef”) were erected on strategic hilltops a few kilometers away from the settlement’s core. Although the latter was dismantled by the Israeli authorities in 2009, it was subsequently rebuilt and remains in situ today.

Additionally, at least 440 dunums of land have been taken over by settlers to grow vines, olives, almonds and field crops. With the exception of one 18-dunum plot, all this land is privately owned by Palestinians. In a few cases, complaints by landowners led to the Israeli authorities issuing evacuation orders against the settler squatters and uprooting seedlings planted by them. However, access restrictions and continuous settler intimidation (see below) severely limit the ability of Palestinian farmers to resume cultivation of their land.[26]

Elon Moreh settlers have also taken advantage of the impressive views from some hilltops to develop six tourist lookout points, with the financial support of official bodies.[27] An additional tourist site was developed around ‘Ein al Kbireh spring (renamed ‘Ein Kfir) which historically served as Deir al Hatab’s main water source.[28] Although the authorities demolished a settler-built pool and a memorial erected next to the spring for lack of a permit in 2010, settlers have reconstructed and expanded the site, which remains intact today.

Elon Moreh settlers have also developed a widespread internal grid of dirt roads extending over nearly 30 kilometres to connect the multiple sites across the de facto boundaries. As with the rest of the infrastructure, this network benefits from the lack of enforcement of planning regulations by the Israeli authorities.

Discouraging Palestinian access

In a series of group discussions conducted by OCHA, residents of the villages affected reported that the presence of armed settlers within the settlement-controlled area, primarily the settlement security coordinator and guards, has played a critical role in intimidating and discouraging them from accessing their land.[29] Soldiers stationed in a military base within the area are also responsible for patrolling the area and backing up the settlement’s security coordinator.

The intimidating effect of an armed settler presence has been compounded by sporadic attacks against farmers and their property. The group discussions suggested that the attacks were at their highest during the years of the second Intifada (2000-2005), although comprehensive documentation is not available for this period. Since OCHA began to document settler violence in 2006, 37 attacks resulting in Palestinian injuries (eight incidents) or property damage (29 incidents) have been recorded around Elon Moreh. This figure excludes prevention of access, trespass onto Palestinian property or the expulsion of farmers from their land through intimidation, all incidents that occur on a more frequent basis. Of at least ten complaints filed with the Israeli police and followed up by the Israeli human rights group Yesh Din, only two have led to the indictment of suspects and the rest were closed on the grounds of lack of evidence.

Palestinian access to the area has been also impeded by physical obstacles. In 1995, the construction by Israel of the Nablus bypass road connecting Elon Moreh to the south[30] separated the three villages from their farming land. Following the start of the second Intifada in 2000, Palestinians were prohibited by the army from using this road, although no written order had been issued to that effect. In practice, this road and the related ban serve to demarcate the western boundary of the area under de facto settlement control.

In recent years, the Israeli authorities have allowed Palestinians access to the Elon Moreh-controlled area twice a year, for a few days on each occasion, during the olive harvest and ploughing season, subject to prior coordination with the military. During these days, the entry of Israeli settlers to the specific areas is officially banned and Israeli soldiers are deployed on the ground to prevent confrontations. According to an official Israeli map, there are eight such sections encompassing approximately 2,500 dunums, or less than a quarter of the private Palestinian land within this area. However, farmers reported that the designated areas immediately adjacent to the settlement’s built-up area have remained entirely inaccessible.

Many of these access restrictions by both the army and settlers followed acts of violence by Palestinians and have often been justified by settlers as a security response. In the focus group discussion, Palestinians alluded to the killing of a nine-year-old child from Elon Moreh in 1987, attributed to Palestinians, as the trigger for the first wave of restrictions.[31] Since, eight Israeli settlers have been killed in or next to Elon Moreh; the last incident occurred on 1 October 2015, when armed Palestinians shot and killed a settler couple en route to the settlement. In the wake of this incident, the military strengthened the ban on Palestinian use of the Nablus bypass road.

Ismael Anees, Deir al Hatab

"My family owns 224 dunums of land close to the settlement, which we can only access during the olive harvest for one or two days a year. We cannot plough the land or pick the olives properly. The few days we’re allowed are also nerve-racking because of army and settler presence. Sometimes, they [the settlers] pick the good olives before we are allowed to reach our land... One of the settlers set up a sheep farm on part of my land and fenced it around. To get to it I need his permission and need him to open the gate. He controls the land, which he ruined with his sheep.

"My family owns 224 dunums of land close to the settlement, which we can only access during the olive harvest for one or two days a year. We cannot plough the land or pick the olives properly. The few days we’re allowed are also nerve-racking because of army and settler presence. Sometimes, they [the settlers] pick the good olives before we are allowed to reach our land... One of the settlers set up a sheep farm on part of my land and fenced it around. To get to it I need his permission and need him to open the gate. He controls the land, which he ruined with his sheep.

"I’m not the only one who suffers. About 8,000 dunums that belong to Deir al Hatab are inaccessible to their owners because of the settlement, the close military zone, the bypass road, etc. I was born in this land and spent my childhood on it. The land is our life and we’ve been deprived of it."

Shrinking space and reduced livelihoods

Based on statistics about the scope of land cultivation outside of built-up areas in the Nablus governorate, it is estimated that there are over 12,000 dunums of cultivable land within Elon Moreh’s de facto boundaries. Assuming free access, cultivation of this area on the same model observed in the rest of the governorate (in terms of scope of irrigation and variety of crops), and assuming the same rates of return, would generate an output of approximately $3.3 million a year.[32] This is a conservative estimate based on the existing limited irrigation and excluding other significant income-generation activities such as herding. The severe constraints impeding Palestinian access to this area mean that only a negligible portion of this economic potential is being realized.

The three Palestinian communities affected by Elon Moreh’s de facto expansion face a fragile socio-economic situation:

- The unemployment rate in Deir al Hatab and Salem ranges between 25 and 30 per cent, while in Azmout it may have reached 50 per cent, according to estimates by village councils, compared with 17 percent in Nablus governorate as a whole;[33]

- 119 families (approx. 600 people) are classified as “hardship cases” thus receiving cash assistance from the Palestinian Ministry of Social Development (MoSD); [34]

- 139 households (approx. 700 individuals) not covered by the MoSD require food assistance (food rations or vouchers) provided by the UN’s World Food Programme (WFP).

The restoration of permanent access and security for Palestinians to their land in the settlement-controlled areas would not only increase respect for international humanitarian law and international human rights law, but would also generate much-needed livelihood and employment opportunities to alleviate the hardship of families affected by unemployment and food insecurity. The return of land to its Palestinian owners and its cultivation would also generate an economic spillover effect, with the additional income spent on local goods and services to multiply the impact of the initial growth.

[19] Since 1967, about 250 Israeli settlements and settlement outposts have been established across the occupied West Bank, including East Jerusalem. This violates Article 49 of the Fourth Geneva Convention, which prohibits the transfer by the occupying power of its own civilian population into the territory it occupies. This has been confirmed numerous times, among others by the International Court of Justice (Advisory Opinion on the Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory of 9 July 2004); the High Contracting Parties to the Fourth Geneva Convention (Declaration from 5 December 2001); and the United Nations Security Council (Resolutions 471 of 1980 and 2334 of 2016).

[20] Cases were selected to represent different geographical areas of the West Bank and the extent to which settlement activities in each of the cases has been addressed by humanitarian actors

[21] For additional information on the impact of the establishment and expansion of Elon Moreh on nearby villages, see B’Tselem, Expel and Exploit: The Israeli Practice of Taking over Rural Palestinian Land, December 2016

[22] HCJ 390/79, Azat Muhammad Mustafa Dweiqat and 16 Others v. Government of Israel et al. For further background, see B’Tselem, Under the Guise of Legality, February 2012, pp. 9-18

[23] Military Order 783 regarding the administration of Regional Councils (1979), Map of Elon Moreh, 21 January 1998

[24] This finding is based on a series of nine focus group discussions with residents of the three Palestinian communities affected, supplemented by dozens of visits and analysis of aerial pictures of the area since the late 1980s that show trends in cultivation, the development of built-up areas, appearance of new roads, etc.

[25] Calculation based on a GIS layer obtained from the Israeli Civil Administration (ICA) marking the status of land in the affected area as either privately owned or public (also known as “state”) land.

[26] The eviction order was issued on the 17 December 2007 and refers to 75 dunums of land. In January 2007 the military commander for the West Bank enacted a “stop disruptive use” order that allows settlers to be evicted from land they have taken over up to three years (subsequently extended to five years) after the takeover is discovered. In the following seven years, the ICA has issued 25 eviction orders, of which seven have actually been enforced.

[27] These include the Nature and Parks Authority, the Ministry of Tourism and the Shomron Regional Council.

[28] In 1982, the installation of a pipeline connecting the spring to the community directly supplied about two thirds of the village households. This pipeline was severely damaged during work to open the bypass road connecting Elon Moreh to the south in 1994. A few years later, the pipeline was disconnected entirely as the community was being supplied by the Israeli water company (Mekorot).

[29] The military orders also define the “guarding area” within which coordinators and guards are authorized to operate. In the case of Elon Moreh, this area includes slightly more than 2,000 dunums. However, this order appears to be of little practical relevance as the area of operation of Elon Moreh’s security coordinators and guards has extended over the entire de facto boundaries of the settlement. For further background on the issue, see Yesh Din, The Lawless Zone, June 2014

[30] Construction of this road was part of the redeployment of Israeli forces under the Interim Agreement between the PLO and Israel (also known as the Oslo II Agreement).

[31] Although the murderer was never found, Rami Haba was acknowledged after his death to have been a victim of terror activity, a status granted by a special committee of the Israeli MoD. This status provides some financial benefits to the families of victims. See here.

[32] Agricultural economic potential was estimated by FAO based on data provided by OCHA on the size of the affected areas and by PCBS (2007/8) on cultivation patterns in Nablus governorate.

[33] Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, Labour Force Survey, Annual Report 2015, p. 78. These rates are well above the 17 per cent average for Nablus governorate as a whole.

[34] Allocations range from NIS 750 to NIS 1,800 every three months depending on the severity of the case.