2015 Overview: Movement and access restrictions

In this section

-

OPT overview

-

Latest developments: January-April 2016

-

Main trends in the Gaza Strip

-

Main trends in the West Bank

OPT Overview

Israel restricts Palestinian movement within the OPT, including between the Gaza Strip and West Bank, through a combination of physical obstacles, bureaucratic constraints, and the designation of areas as restricted or closed. Combined, these restrictions impede access to services and resources, disrupt family and social life and undermine Palestinians’ enjoyment of their economic, social and cultural rights, undermine livelihoods and compound the fragmentation of the OPT.

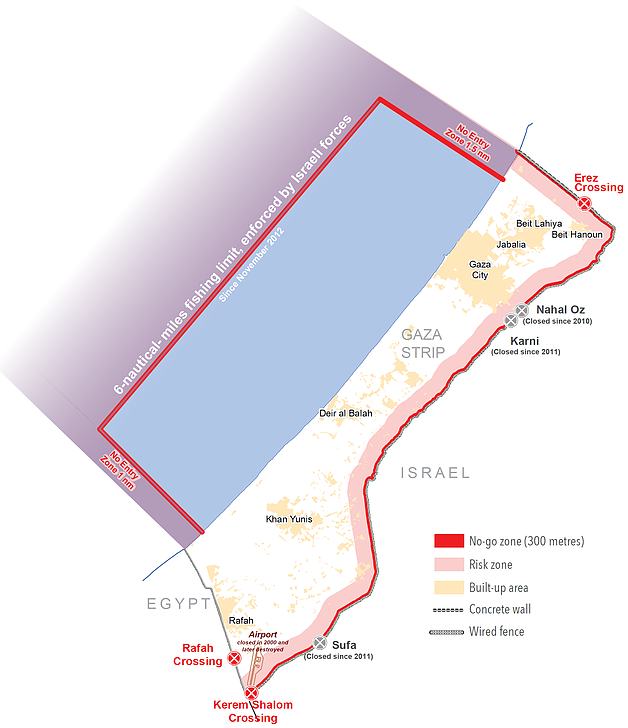

Fenced in on its land borders with Israel and Egypt, and with no control over its airspace or territorial waters, access from the Gaza Strip to the outside world is restricted to three land crossings, controlled by Israel (Erez and Kerem Shalom) and Egypt (Rafah). While the Israeli blockade remains a form of collective punishment of the civilian population,[1] 2015 witnessed a significant relaxation of restrictions by the Israeli authorities, as evidenced in an increase in the volume of Palestinians from Gaza, in particular businessmen and patients, permitted to leave through the Erez crossing: a limited passage of Muslims and Christians to the holy places in the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, also continued.[2] The easing of restrictions also resulted in a significant increase in the amount of goods allowed in and out of Gaza for commercial purposes through the Kerem Shalom crossing.

However, the other three Israeli-controlled crossings, Nahal Oz, Sufa and Karni, remained closed in 2015, while the vast majority of the smuggling tunnels under the border with Egypt remained inoperative. The Egyptian-controlled Rafah crossing also remained largely closed in 2015, including for humanitarian assistance.

Physical obstacles such as the Barrier and checkpoints, and administrative requirements, particularly permits, restrict Palestinian access and movement within the West Bank, including into East Jerusalem, areas isolated by the Barrier, ‘firing zones’, the Israeli-controlled area of Hebron city (H2), and land around or within Israeli settlements. In recent years, the Israeli authorities have eased some long-standing restrictions in the West Bank, improving Palestinian access to key urban hubs. This trend continued into 2015, with a lifting of permit requirements to enter East Jerusalem and Israel for all male West Bank ID holders above 55 years and women above 50 years. The wave of violence that spread throughout the West Bank in the latter part of the year resulted in increased restrictions on Palestinian movement throughout, with the Israeli authorities citing security concerns.

Latest developments: January-April 2016

- During the first few weeks of 2016, the Israeli authorities removed some checkpoints and roadblocks deployed in previous months throughout the West Bank, easing Palestinian access to services and livelihoods. This has been particularly evident across the Hebron governorate, except in the Israeli-controlled part of Hebron city (H2) where severe restrictions remained and in some cases intensified. On the other hand, since the beginning of 2016, following Palestinian attacks, the Israeli authorities have consolidated the practice of blocking some or all of the main routes to the villages where the suspected perpetrators lived, raising concerns about collective penalties.

- Between 3 April and 22 May, Israel suspended the entry of cement to the Gaza Strip for the private sector, following a diversion of cement from its legitimate beneficiaries, as well as the discovery of a tunnel running under Gaza to Israel. By contrast, also in April, the Israeli authorities expanded the fishing area, along the southern Gaza coast, from six to nine nautical miles, while retaining the current six-nautical-mile fishing limit along the northern coast.

- The Rafah crossing has been continuously closed since 24 October 2014, with exceptional partial openings on 42 days, as of the end of April 2016.

Main trends in forced displacement

Gaza Strip

2015 was marked by a continuation of the relaxations introduced by the Israeli authorities in the aftermath of the 2014 hostilities and resulted in a significant increase in the number of crossings of people via Erez and the volume of goods via Kerem Shalom. However, the remaining restrictions on external trade, including with the West Bank, and on access to agricultural land and fishing waters, are key factors discouraging investment and perpetuating high levels of unemployment, food insecurity and aid dependency. According to the Israeli authorities, the access restrictions they impose on the Gaza Strip are security measures addressing a range of threats, including the smuggling of weapons, the firing of rockets and the digging of offensive tunnels. The inability of the Government of National Consensus to assume control over of the Palestinian side of the crossings due to the ongoing internal divide has added additional challenges. The humanitarian impact of the blockade is also exacerbated by the almost-continued closure by Egypt of the Rafah passenger crossing since October 2014, leaving the vast majority of the 1.8 million Palestinians living in Gaza unable to leave.

Access restricted areas (ARA)

Citing security concerns, including rocket firing and digging of tunnels, Israeli forces continued to enforce a buffer zone by land and sea, the “Access Restricted Areas“ (ARA), including through the firing of live ammunition, land levelling, destruction of property, arrests, and the confiscation of equipment. By sea, since 2013, Israel has enforced a six-nautical-mile fishing limit along the entire Gaza coast; Israel and Egypt also impose a “no fishing zone” along their respective maritime boundaries with Gaza.

The exact extent where access is permissible by land remains unclear. Areas up to 300 metres from the perimeter fence are generally considered to be a “no-go” area and up to 1,000 meters “high risk”, which discourages farmers from cultivating these areas. In some cases in 2015, special coordination was granted to international organizations to implement projects up to 100 metres from the fence.

Rafah Crossing

Rafah has been largely closed, including for humanitarian assistance, since 24 October 2014: in 2015 there were 32 days of partial openings. Of a total of 1,670 patients referred by the Palestinian Ministry of Health to Egypt, 178 patients were able to cross to Egypt. Prior to the closure, a monthly average of 4,000 people crossed Rafah for health related reasons.[3] By year’s end, at least 30,000 Palestinians registered as humanitarian cases were waiting to cross Rafah and an unidentified number of Palestinians were stranded in Egypt waiting to return.

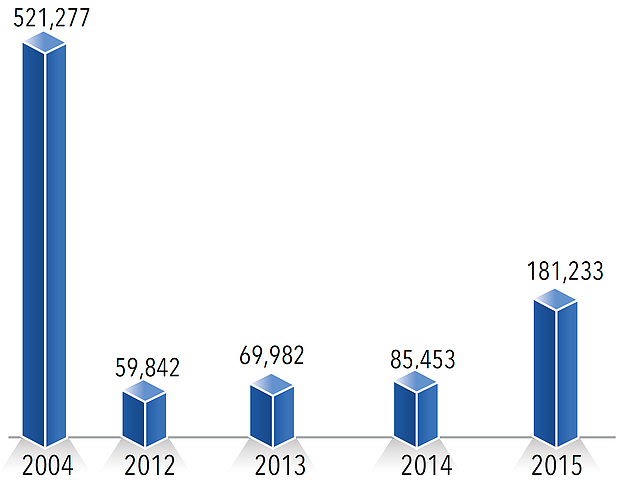

Kerem Shalom Crossing

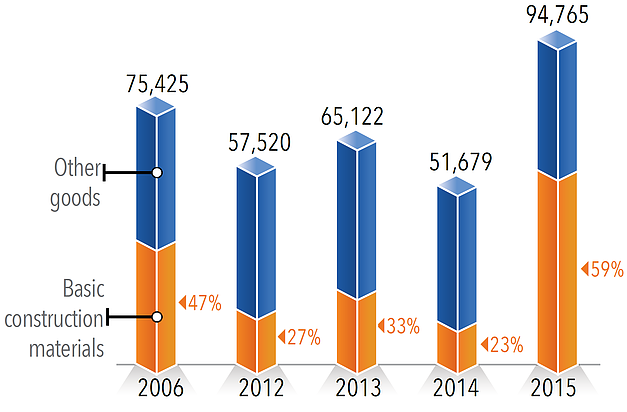

Imports: Israel expanded the Kerem Shalom crossing and allowed in 88 per cent more imports compared to the previous year, amounting to 64 per cent of the total imports prior to the imposition of the blockade. The “dual use” list of goods (items that could be used for military as well as civilian purposes) was revised three times during 2015, removing a longstanding restriction on the import of gravel, but banning previously-approved items, including wooden boards thicker than 1 cm.

Imports: Israel expanded the Kerem Shalom crossing and allowed in 88 per cent more imports compared to the previous year, amounting to 64 per cent of the total imports prior to the imposition of the blockade. The “dual use” list of goods (items that could be used for military as well as civilian purposes) was revised three times during 2015, removing a longstanding restriction on the import of gravel, but banning previously-approved items, including wooden boards thicker than 1 cm.

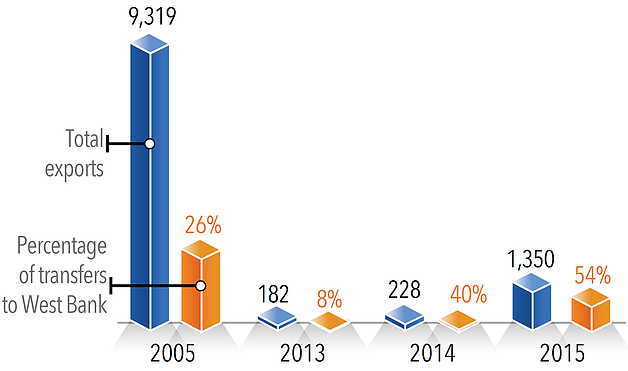

Exports: For the first time since the imposition of the blockade in 2007, Israel allowed the export of goods to Israel. In 2015, there was six-fold increase in exports and transfers from Gaza compared to 2014. Total exits are still 14.5 per cent of a wider range of exports that left Gaza for Israel, the West Bank and the external world in 2005, prior to the imposition of various restrictions ending in a full blockade in 2007.

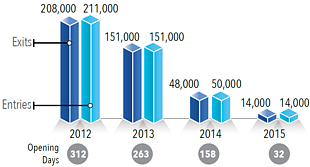

Erez Crossing

The number of Palestinians permitted by Israel to cross through Erez more than doubled in 2015 compared to 2014, with businessmen and patients and their companions accounting for the highest category. Israel raised the monthly quota of merchant-permits from 3,000 to 5,000, and daily exits of merchant permit-holders from 400 to up to 800. During the year, there was an increase in the absolute number of medical permits issued, along with a decline in approval rates which, by the end of December, was the lowest (67 per cent) since May 2009. Restrictions were also placed on patient companions, including raising the minimum age to 55.

Entries into Israel

Exports/transfers from Gaza (truckloads)

Imports/transfers to Gaza (truckloads)*

West Bank, including East Jerusalem

The trend of recent years of easing some of the restrictions on Palestinian movement continued into 2015, including during the Ramadan period, which saw some Gaza pilgrims granted permits to visit Al Aqsa Mosque for the first time since 2000. However, the escalation of violence in the latter part of the year witnessed a re-imposition of some of physical and administrative measures by the Israeli authorities, citing security needs. These disrupted access to services, including educational and health facilities, places of work, and holy sites, forcing people to take longer and more costly routes.[4]

East Jerusalem

Heightened tensions during September, in conjunction with an increase in the entry of Israelis to the Al Haram Al Sharif / Temple Mount, led to a select list of Palestinians prohibited from entering the compound. An increase in attacks and violence in October led to the deployment of about 40 new checkpoints and roadblocks, systematically restricting the movement of Palestinian residents of East Jerusalem, and affecting 138,000 people in nine neighbourhoods. The majority of these obstacles were gradually removed, with eight obstacles still in place by the end of the year.

The Barrier

The Barrier

The Israeli authorities resumed construction of a section of the Barrier in the Cremisan valley extending from Beit Jala to the village of Walaja in the Bethlehem governorate. While this construction was approved by the Israeli Supreme Court, it contravenes the International Court of Justice’s Advisory Opinion of 2004. In total, 56 km of the Barrier’s route are located within Bethlehem governorate. If completed as planned, 58 Palestinian farming families will be separated from approximately 3,000 dunams of land.

Northern West Bank

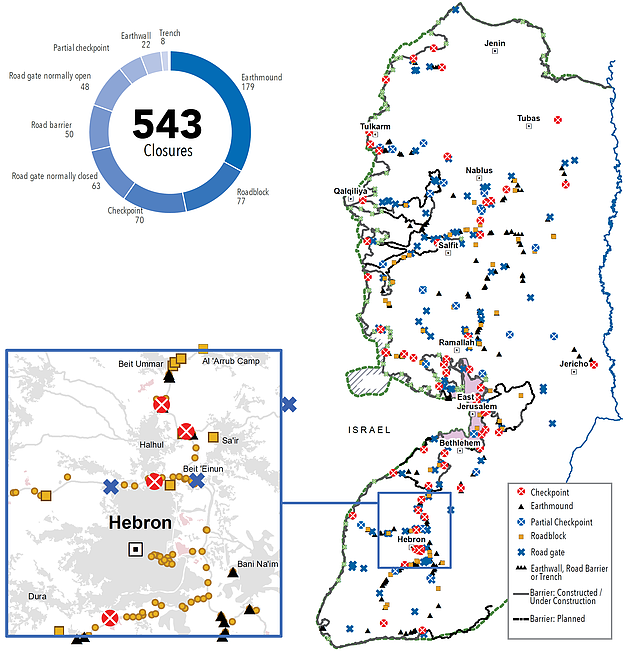

During October, Israeli forces intensified movement restrictions following the killing of an Israeli couple in the Nablus governorate: as of 31 December, there were 18 new obstacles, in addition to 167 pre-existing obstacles. These include two checkpoints (Huwwara and Za'tara) which were intermittently closed without prior notice, and the turning of a road (Nablus eastern bypass) into an Israeli-only road, diverting Palestinian traffic into a longer and more congested detour.

Hebron governorate

Following a series of attacks and alleged attacks in the governorate, movement restrictions in Hebron peaked in November, with 53 obstacles deployed, in addition to 109 pre-existing obstacles,[5] blocking or restricting all routes, including dirt roads, leading to Hebron city. Palestinian access to the settlement area within the Israeli-controlled part of Hebron City (H2) was further restricted.[6] Most restrictions remained in place as of the end of 2015, and resulted in long delays and disruptions to services and livelihoods, including access to hospitals and schools.

Following a series of attacks and alleged attacks in the governorate, movement restrictions in Hebron peaked in November, with 53 obstacles deployed, in addition to 109 pre-existing obstacles,[5] blocking or restricting all routes, including dirt roads, leading to Hebron city. Palestinian access to the settlement area within the Israeli-controlled part of Hebron City (H2) was further restricted.[6] Most restrictions remained in place as of the end of 2015, and resulted in long delays and disruptions to services and livelihoods, including access to hospitals and schools.

- Over 4,000 children go to 15 schools located in the H2 area, who were affected by access restrictions.

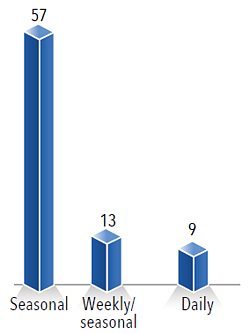

Closure obstacles as of 31 December 2015

Endnotes

[2] Since November 2014, Israel has allowed a weekly average of 200 Muslims to visit Al Aqsa Mosque and continued to grant Christian Palestinians permits to visit holy sites in the West Bank twice a year, with a total of 996 exits recorded in 2015 compared to 945 in 2014. Israel also granted 161 permits to students to travel via Erez to reach academic institutions abroad.

[3] http://www.emro.who.int/images/stories/palestine/documents/WHO_monthly_Gaza_access_report-December_2015-final.pdf?ua=1

[4] Two Palestinians died on their way to hospitals after being delayed at newly-established checkpoints: the elderly, ill, disabled and women were disproportionately affected groups.

[5] These include around 95 obstacles and permanently staffed checkpoints, in the over 20% of Hebron City, known as H2, where Israel continues to exercise full control. This area is home to over 6,000 Palestinians.

[6] This included a sweeping ban on the crossing of Palestinian males aged between 15 and 25 through certain checkpoints, as well as the requirement from residents of these areas to register with the Israeli authorities in order to be allowed through other checkpoints.