Concern over conditions and violence against Palestinian children in detention

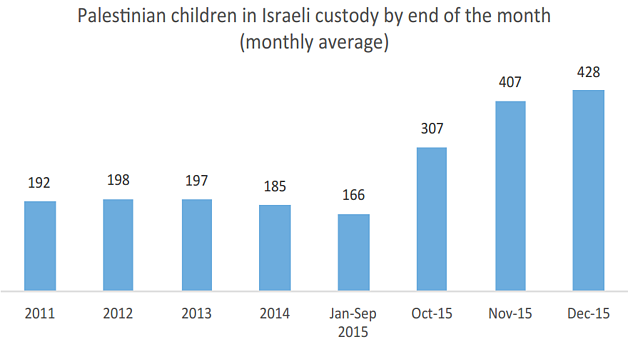

Amid heightened violence in late 2015, the number of Palestinian children detained by the Israeli authorities spiked to the highest figure since March 2009: at the end of December, 428 Palestinian children were in the Israeli prison system. Some 80 per cent of these children were in pre-trial detention, the majority of them facing charges of throwing stones.

According to information collected by OCHA, between 1 October 2015 and 31 January 2016 there were 32 stabbing attacks and alleged attacks by Palestinian children, which resulted in the death of two Israelis and the injury of another four; 25 of the Palestinian children involved in these incidents were shot and killed on the spot, and another seven were injured and/or arrested.

In response to the rising number of child detainees, the Israel Prison Services used a section of Givon Prison, inside Israel, to house the overflow of Palestinian minors. Conditions at the prison were inadequate and failed to meet minimum standards, according to information gathered by Defense for Children International-Palestine (DCIP): cells were crowded, the building lacked proper heating and shower facilities, and children complained of poor quality and inadequate amounts of food. This prison section was reportedly closed down at the end of December.

Of particular concern is the detention of six Palestinian teenagers under administrative detention, which is imprisonment without charge or trial. This is the first time the measure has been used against Palestinian minors in nearly four years.

Harsher legislation

Over the past few months, Israeli authorities took legislative measures establishing harsher sentencing guidelines and fines for children in Jerusalem. These amendments include a 10-year prison sentence for throwing stones or other objects at moving vehicles with the possibility of endangering passengers or causing damage, and 20 years for throwing stones with the purpose of harming others. The amendments reduced judicial discretion, instituting a mandatory minimum sentence of no less than one-fifth of the potential maximum sentence, and restricting suspended sentences to special circumstances only.

One of the latest bills proposes custodial sentences for children as young as 12 convicted of “nationalistic-motivated” violent offences. The actual serving of the sentences would be deferred until children reach the age of 14. In the remainder of the West Bank, where military law applies to the Palestinian population only, children can be imprisoned from the age of 12.

According to the explanatory introduction to the bill: “The seriousness that we attach to terror and acts of terror that cause bodily injury and property damage, and the fact that these acts of terror are being carried out by minors, demands a more aggressive approach, including towards minors who are convicted of offenses, particularly serious offenses.”

Treatment during detention and interrogation

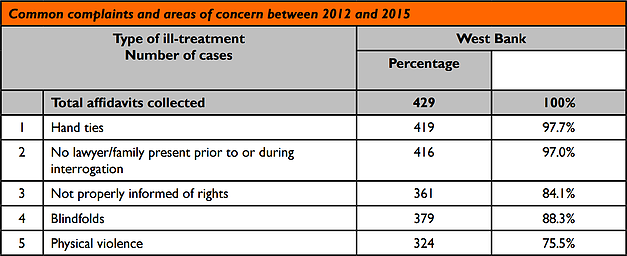

The treatment of children during detention and interrogation is a concern. Affidavits collected by DCI from 429 Palestinian children in the West Bank detained by Israeli forces between 2012 and 2015 indicate that three-quarters of the children endured some form of physical violence following arrest. In 97 per cent of these cases, the Israeli authorities deprived children of legal counsel prior to an interrogation and did not allow their parents to be present during questioning.

Under house arrest[1]

Malek Shqeir is the second child in a family of seven children from Jabal al Mukabbir, East Jerusalem. On 19 November 2015, a month before his 16th birthday, Israeli forces arrested him on suspicion of throwing stones. On 14 December, pending a sentence on this case and after paying a bail of NIS7,500 ($1,920), Malek was released and placed under open-ended house arrest in Abu Ghosh, a town inside Israel, 30 minutes away from East Jerusalem. According to the family, the Israeli attorney refused to allow Malek to be placed under house arrest at his home or nearby.

Malek Shqeir is the second child in a family of seven children from Jabal al Mukabbir, East Jerusalem. On 19 November 2015, a month before his 16th birthday, Israeli forces arrested him on suspicion of throwing stones. On 14 December, pending a sentence on this case and after paying a bail of NIS7,500 ($1,920), Malek was released and placed under open-ended house arrest in Abu Ghosh, a town inside Israel, 30 minutes away from East Jerusalem. According to the family, the Israeli attorney refused to allow Malek to be placed under house arrest at his home or nearby.

To abide by the court conditions, the family had to rent a house in Abu Ghosh and arrange for a guardian, including his two grandfathers, to stay with Malek 24 hours a day. His father is a bus driver and is the family’s sole breadwinner: “We have to pay NIS2,900 to rent the house, NIS2,000 for transportation between Jabal al Mukabbir and Abu Ghosh, and NIS4,000 for monthly expenses. This has forced us to borrow money from relatives,” said his father. Malek concluded: “Once this comes to an end, I want to continue my schooling and study law at Al Quds University, just like my elder brother.”

According to the Committee for the Parents of Prisoners in East Jerusalem, there are currently around 50 Palestinian children under house arrest, some of whom are staying in houses other than their homes, including outside East Jerusalem. Although it offers certain advantages over imprisonment, the practice of placing children under house arrest can have an impact on family relations as a result of the home becoming a prison and can affect the psychological well-being of these children, especially if they are also denied the right to go to school in cases of full house arrest.

UNICEF-Israel dialogue on child detention

Since March 2013, UNICEF has engaged in dialogue with the Israeli authorities on children’s rights while in military detention and on specific actions that can be undertaken to improve the protection of these children. The dialogue focuses on what a child experiences when arrested and detained for alleged security offences in the West Bank and during contact with various Israeli authorities. UNICEF advocates for the universal principle that all children in contact with law enforcement and justice institutions (whether juvenile justice systems or military systems) have the right to be treated with dignity and respect at all times and to be afforded special protection. In the context of this dialogue, Israeli forces began in February 2014 to replace the practice of night arrests of children suspected of security offences with a summons procedure. This pilot, which is still ongoing, tackles some of the protection concerns , that occur during the first 48 hours of arrest, transfer and detention of children. Sample data collected by UNICEF since 2013 has indicated a moderate decline in the percentage of night arrests.

* This article was contributed by Defense for Children International-Palestine (DCIP), a member of the UNICEF-led Working Group on Grave Violations against Children, which reports to the Protection Cluster and the Humanitarian Country Team for the OPT.

[1] This case study was compiled by OCHA.