Exports from Gaza undermined by the blockade

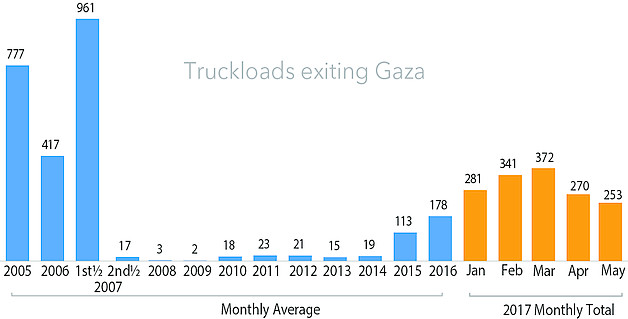

As part of the blockade imposed in 2007 following the takeover of the Gaza Strip by Hamas, Israel completely banned exports. This resulted in a dramatic decline in manufacturing activities and a rise in unemployment. In 2010, the export ban was eased slightly to allow the exit of minimal quantities of goods, primarily cut flowers and strawberries to overseas markets only. Following the 2014 conflict, commercial transfers from Gaza to the West Bank resumed, first for agricultural produce and later for textiles and furniture; after March 2015, limited exports were also permitted from Gaza to Israel.

Despite significant progress, a range of other constraints, including restrictions on imports of certain raw materials considered by Israel to have a dual military-civilian use, have resulted in the volume of goods exiting Gaza in 2016 falling by less than 20 per cent from those in the first half of 2007, prior to the imposition of the blockade.

Mujahed Al Sousy from Jabalia, Gaza

March 2015: “We are shocked that Israel is banning the entry of wooden planks”

Mujahed Al Sousy is the general manager of the Sousy Furniture Company in Jabalia. Before the 2007 blockade, the company employed between 150 and 200 skilled workers and exported between 20-25 truckloads each month: 80 per cent went to Israeli markets, 19 per cent to the West Bank and one per cent was sold in the local market in Gaza. With the imposition of the blockade in 2007, the exit of goods was banned and production was limited to the Gaza market, which has a very limited purchasing power. The number of workers the company could employ was radically reduced.

In November 2014, Israel allowed the resumption of furniture transfers to the West Bank for the first time since 2007. However, the hopes of furniture producers were short lived: in February 2015, Israel included wooden planks thicker than 2.5 centimetres in the list of items considered to have a dual military-civilian use and banned their import into Gaza. This undermined any significant reactivation of the sector.

“We face other challenges in transferring furniture out of Gaza. Our shipments must be palletized to only one metre in height and there are steep logistical costs because of the loading and offloading for security … Now we are shocked that Israel is banning the entry of wooden planks thicker than 2.5 centimetres. How can I compete in West Bank markets with all these additional costs and problems?”

Published in March 2015 Humanitarian Bulletin

June 2016: “I have been paying out of my own pocket to keep the business going”

“The situation is slightly better, if still challenging,” said Mujahed when revisited in June 2017. ”Since 2016, the Israeli authorities have allowed exports of furniture to Israel and have increased the height of pallets from 1 to 1.2 metres.

We now export one truckload to Israel each month and employ about 50 workers. This is a marginal improvement but better than nothing. We were major exporters of solid wood dining tables and chairs. The variety of our products has shrunk and is limited by the type of wood, mostly plywood, that we are allowed to import from Israel.

Our ability to compete is severely challenged by many factors: the ban on the entry of raw materials essential for our main products, dining tables and chairs; the longer power cuts and the increasing price of fuel to operate backup generators; and the high transportation costs for both exports and imports. Prior to the blockade, all shipments took place via the Karni crossing, which is geographically closer to our factory than Kerem Shalom. Loading a truck via Kerem Shalom costs NIS 3,500 to NIS 5,000, while in Karni we used to pay NIS 800 to NIS 1,200.

With the renewal of exports to Israel, I feel like a newborn who is learning about life afresh. We have to start all over again and find new clients in Israel as some of our original clients went bankrupt after the blockade. I would not call what we do now production. We don’t generate a profit and can barely cover our costs. For years we’ve been running at a loss. I have been paying out of my own pocket to keep the business going in the hope that the blockade will be lifted and the political situation will get better.”