The Gaza Strip: The Long Term Impact of the 2014 Hostilities on Women and Girls | December 2015

Facts

Facts

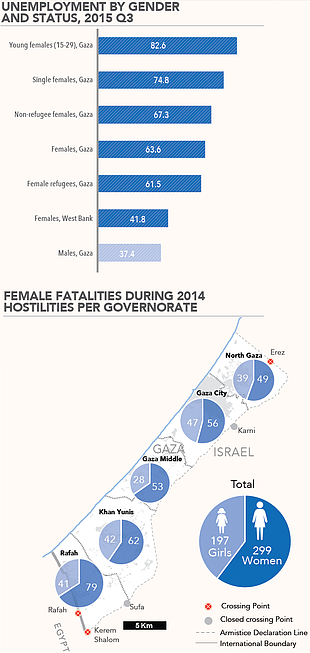

- 299 women, of whom at least 16 were pregnant, and 197 girls were killed over the course of the 2014 summer hostilities in the Gaza Strip, and more than 2,000 women and hundreds of girls were injured (Protection Cluster and MoH).

- At least 790 women were widowed as a result of the 2014 hostilities (Ministry of Women’s Affairs, 2015).

- During the second half of 2014 the number of registered cases of maternal and neonatal mortality doubled compared to the first half of the year (UNFPA and UNRWA).

- Approximately 24,300 girls and 22,900 women whose homes were destroyed or severely damaged during the hostilities, remain displaced in precarious conditions (IDP Registration Survey, Q4 2015).

- Over 8% of households in Gaza are headed by women (PCBS, 2015).

- 28.6% of females in Gaza up to 49 years of age were married before they reached 18, and 2.6% before they reached 15 (PCBS, 2014).

- More than 70% of households in Gaza receive 6-8 hours piped water once every two to four days, and the entire population suffers from scheduled electricity blackouts for 12-16 hours a day.

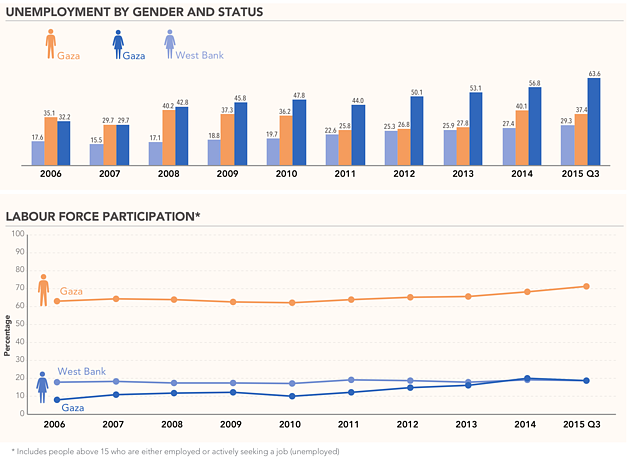

- Approximately 20% of working age females in Gaza participate in the labour force, one of the lowest such rates in the world (PCBS, 2015).

- The unemployment rate among females in Gaza in the third quarter of 2015 exceeded 63%, compared to 37% among males, and double the equivalent rate in 2007 (30%), prior to the imposition of the blockade (PCBS, 2015).

- Women and girls in the Gaza Strip have been disproportionately affected by the 2014 summer hostilities in multiple aspects of life. This has exacerbated pre-existing vulnerabilities stemming from the longstanding Israeli blockade and the discrimination against women within Palestinian society. Of particular concern is the situation of widows, internally displaced females, women and girls with disabilities, adolescent girls, and female farmers.

- The living conditions of displaced girls and women, currently accommodated with host families, in rented apartments, prefabricated units, tents and makeshift shelters, or in the rubble of their previous homes, raise a range of protection concerns. These include lack of privacy and increasing exposure to gender-based violence and harassment. The traditional retention of property rights by men, including rights over homes and land destroyed or damaged during the war, impedes the access of displaced women to legal and shelter-related assistance by humanitarian actors.

- The general decline in the access of people to basic services, especially water and electricity as a result of damage to infrastructure, has undermined the ability of women and girls to engage in income generating activities or allocate time to their own needs. This is directly linked to the customary division of labour in the Palestinian society, where women and girls bear the primary responsibility for the functioning and maintenance of households, which have became more time-consuming. It is also linked to the limited opportunities for females in the labour market. This division of labour continues to apply to married women with disabilities, who face as a result additional hardship.

- The extensive damage to agricultural and grazing land over the course of hostilities has had a significant impact on the employment opportunities available to women. This is due to the large percentage of working women that were employed in the agriculture sector, including informal employment in herding, food processing and vegetable gardening. Additionally, due to structural barriers, only a negligible percentage of women involved in agriculture have ownership over land, thus increasing the risk of exclusion from agriculture-related assistance.

- Precarious living conditions and overcrowding, particularly among IDPs, along with the loss of productive assets, often lead to the adoption of negative coping mechanisms, such as drop out of children from school and early marriage of girls. The latter practice reduces the economic burden on the girls’ families and is often perceived as a “protective measure” for the girls being married, but severely limits their opportunities for personal development.

- In order to properly respond to the needs of women and girls in the context of post-war Gaza, and contribute to the elimination of all forms of discrimination against women and a full respect to the rights of children, as required by international law, humanitarian actors must fully understand the specific threats and challenges affecting these groups. It is imperative that these actors address the structural barriers that limit the access of girls and women to assistance, among others, through ensuring equity in the delivery of humanitarian assistance, collecting sex and age disaggregated data, and consultations with affected community members.