High numbers of Demolitions: the ongoing threats of demolition for Palestinian residents of East Jerusalem

Many Palestinians in East Jerusalem are subject to a coercive environment with the risk of forcible transfer due to Israeli policies such as home demolitions, forced evictions and revocation of residency status. As is the case in Area C, a restrictive and discriminatory planning regime makes it virtually impossible for Palestinians to obtain the requisite Israeli building permits: only 13 per cent of East Jerusalem is zoned for Palestinian construction and much of this is already built-up. Palestinians who build without permits face the risk of home demolition and other penalties, including costly fines, the payment of which does not exempt the owner from the requirement to obtain a building permit.[1] At least a third of all Palestinian homes in East Jerusalem lack an Israeli-issued building permit, potentially placing over 100,000 residents at risk of displacement.

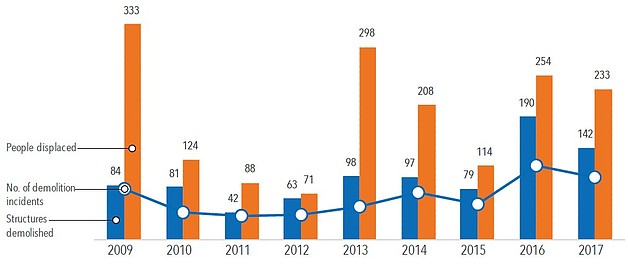

In 2017, the Israeli authorities demolished 142 structures in East Jerusalem for lack of a building permit. This is the second largest number of demolitions since 2000, although lower than 2016 when 190 demolitions were recorded. This year’s demolitions resulted in the displacement of 233 people, including 133 children, and otherwise affected another 631 people. The communities most heavily affected were Jabal Mukabbir, Beit Hanina, al Isawiya and Silwan which, combined, accounted for 72 per cent of demolition incidents and almost two-thirds of all structures demolished this year. Overall, East Jerusalem accounted for a third of all demolitions (142 out of 423) and more than a third of all people displaced (233 out of 664) in the West Bank in 2017. Around 23 per cent of the structures demolished in East Jerusalem were inhabited homes, while agricultural or livelihood-related structures accounted for some 35 per cent of all demolitions.

Structures targeted and people displaced in East Jerusalem by year

In contrast, in Area C of the West Bank, the number of Palestinian-owned structures demolished and people displaced was the lowest since 2010. The 270 structures targeted represented almost half the number documented annually over the last seven years, while the 398 people displaced represented a decline of 40 per cent versus the yearly average in the seven-year period.

The threat remains of further demolitions of homes and other structures in East Jerusalem. Two instances of multiple demolition orders were reported recently in two East Jerusalem localities affected by the Barrier.

The Barrier’s deviation from the Israeli-defined municipal boundary has physically separated some Palestinian localities in East Jerusalem from the urban centre.[2] Although residents retain their ‘permanent resident’ status and pay municipal taxes, these areas have been effectively abandoned by the municipality; basic facilities and services are either degraded or lacking entirely. There are multiple high-rise buildings, with structures springing up within metres of each other and no municipal oversight to ensure basic engineering and safety standards, including for earthquakes and other hazards. Such construction is primarily driven by the lack of municipal enforcement of regulations and penalties, alongside high demolition rates enforced on Palestinians in areas of Jerusalem ‘within’ the Barrier.

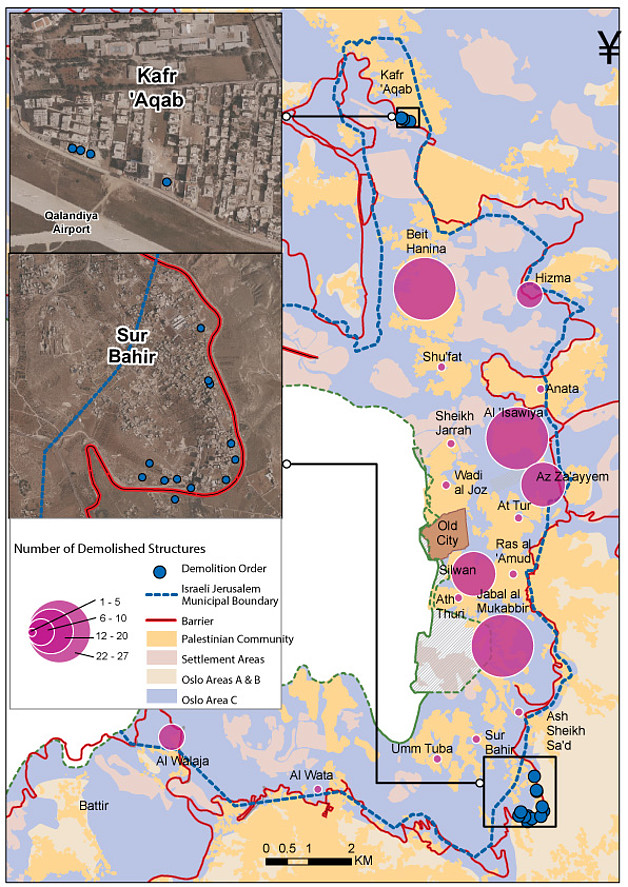

Demolished structures in east Jerusalem in 2017 including Kafr ‘Aqab and Sur Bahir

Demolition orders threaten high-rise buildings in Kafr ‘Aqab

In Kafr ‘Aqab, one of the East Jerusalem localities isolated from the city by the Barrier, no building permit has been issued since 2001.[3] According to the Israeli organization Ir Amim, it appears that no employees of the Building Inspection Division have entered the locality since 2005 and that, “as of 2012, the number of building starts in Kafr ‘Aqab accounted for 83 per cent of the total number of building starts in the entire city of Jerusalem.” [4]

The Jerusalem municipality is now planning to demolish four high-rise buildings in Kafr ‘Aqab following the rejection by a Jerusalem District Court in mid-October 2017 of the residents’ appeal against the demolition orders. The buildings targeted are located adjacent to the Barrier. The municipality plans to demolish them to build an eight-metre-wide public road proposed to alter traffic flows to and from Qalandiya checkpoint. Three of the buildings targeted contain over 60 apartments, which are still uninhabited. The fourth contains over twenty apartments, of which six are occupied. The demolitions would result in the displacement of 25 people, including 13 children. Dozens of families who have purchased apartments in these buildings would be affected, all of whom are Jerusalem ID holders. Most have reportedly invested their life savings to acquire the apartments and are still paying the owner in monthly instalments.

On 5 September, municipality staff, accompanied by Israeli forces, entered the neighbourhood and served residents with judicial demolition orders. Since the Jerusalem District Court ruling on 15 October 2017, the Israeli army and other forces have entered the buildings on multiple occasions, including in the early hours, to photograph the contents and residents, including sleeping children. Neighbours are concerned that demolition of the buildings with explosives will cause collateral damage to adjacent buildings and filed an appeal. In late November, the Jerusalem District Court issued an order halting the demolition and ordering the municipality to respond by the end of January. A discussion on the matter is scheduled for 28 February.

Demolition orders in the ‘buffer zone’ in Sur Bahir

Sur Bahir (population 25,000) is a Palestinian neighbourhood in the southern part of East Jerusalem. The majority of its land falls within the Israeli-defined municipal boundary but Sur Bahir also has land in Area A (187 dunums), Area B (21 dunums) and Area C (691 dunums). Unlike Kafr ‘Aqab, the entirety of the neighbourhood, including areas falling outside the Jerusalem municipal boundary, has been left on the ‘Jerusalem side’ of the Barrier.

Although all the residents hold Jerusalem IDs, the services and infrastructure available vary according to which jurisdiction they reside in. Historically, construction was concentrated in areas located within the Israeli-defined municipal boundary, but population growth and the inability to obtain building permits forced residents to expand into Areas A, B and C, where it is reportedly three times cheaper to buy an apartment than inside the municipal area.

Residents who build in Area A must obtain construction permits from the PA, as stipulated in the Oslo Accords, through Dar Salah village council, located in Bethlehem governorate on the West Bank side of the Barrier. However, according to local community sources, about 70 per cent of structures in Area A have been constructed without PA building permits.

Palestinian families were recently served demolition orders related to 12 buildings or house foundations in the Wadi al Humos area of Sur Bahir. Eleven people, including seven children, reside in two apartments in one building. According to the Israeli authorities, all the buildings are located in an area which has been designated as a Barrier ‘buffer zone’ since 2010 (see map). The area of the buffer zone covers some 160 dunums in areas A and B, and around 200 dunums in Area C, according to local community sources, and includes 200 to 250 buildings.

[1] Between 2000 and 2009, the Jerusalem Municipality collected an average of NIS 20.8 million per year (US$5.8 million) in these fines. Source: For 2004 - 2008, see ICAHD data sheet on East Jerusalem demolitions. Data for 2000 - 2003 and 2009 provided by Meir Margalit. For more details on fines and other penalties, see Margalit, No Place Like Home, pp. 10-12.

[2] The localities primarily affected are Kafr ‘Aqab; the Shufat ridge comprising Shufat camp, and part of Anata; Ras Khamis; Ras Shihadeh; Dahiyat as Salaam; Qalandiya village; part of Hizma; Ash Shayah of As Sawahira Ash Sharqiya; Bir Ona; and part of al Walaja in the Bethlehem area. Estimates of the population in these areas range from 55,000 to 120,000 -160,000 residents, although the ratio of East Jerusalem residents to West Bank ID holders is not known. See East Jerusalem Palestinian localities behind the Barrier, OCHA Humanitarian Bulletin, July 2016.

[3] Munir Zagheir, chairman of the Kafr ‘Aqab Residents Committee quoted in Nir Hasson, ‘In Rare Move, Israel to Demolish Five Palestinian Residential Buildings Behind Separation Barrier’ Ha’aretz, 28 October 2017.

[4] Ir Amim, “Displaced in their own city”, pp. 46, 44. As of the beginning of 2013, some 1,282 new apartments were nearing completion, all in high-rise buildings.