Home quarantine compounds the hardship of thousands of families in Gaza

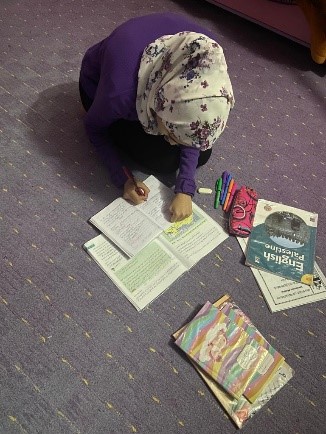

Rana, a 14 -year-old girl from Khan Younis, had to spend three weeks in quarantine at home, after being in contact with a relative who tested positive for COVID-19. She spent this period with her father and siblings, while her mother was outside the country. "I was very afraid of what might happen to us and wasn’t able to do my homework or anything else,” said Rana.

Since the detection of the first case of COVID-19 transmission within the community in the Gaza Strip in late August, the number of people who contracted the virus soared from around 150 to over 39,000 by end December 2020, and fatalities from three to some 350. As the number of cases surged, the local authorities had to adapt the modalities of isolation for those who tested positive or were in contact with them, as well as for those returning to Gaza, via Israel or Egypt.

Instead of being quarantined in a designated centre,[1] since early October, a growing number of people have been referred to home quarantine. While this was initially limited to the family members of infected people and asymptomatic cases, it was subsequently expanded to include people showing light or mild symptoms and returnees. Meanwhile, the ‘institutional option’ (including hospitals) has remained available for people suffering more severe symptoms, as well as those unable to undertake home quarantine.

As of 15 December, of the approximately 8,700 active cases registered in Gaza, 83 per cent (7,200 people) were in home isolation and 17 per cent (1,500 people) were isolated in the two designated hospitals and eight isolation facilities. Another 25,600 people who were in contact with confirmed cases were in home quarantine.[2] Dedicated police forces have been allocated to ensure abidance by the quarantine rules.

The home quarantine has generated additional challenges and hardship for many already vulnerable families, and resulted in gaps in certain services and assistance. To identify the emerging needs and better customize humanitarian responses, the Gaza Inter-Cluster Coordination Group (ICCG)[3] led by OCHA, carried out a rapid multi-sectoral assessment among affected households. Between 8 and 20 November, members of a representative sample of 244 households (HHs), who were in home quarantine during October, were interviewed over the phone using a structured questionnaire.[4]

The following are some key findings:

- Duration of the home quarantine: of those HHs who responded, 60 per cent reported that they stayed in quarantine for three weeks, 36 per cent for two weeks and four per cent for one week.[5]

- Insufficient isolation space: over 50 per cent of HHs where the member who tested positive was at home, reported that they lacked a separate bedroom or bathroom.[6]

- Shortages of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE): nearly 30 per cent indicated that they lack face masks and gloves.

- Psychological distress and related support: nearly 60 per cent reported that at least one family member showed symptoms of psychological distress, and over 80 per cent were unaware of where to receive psychosocial support, if needed.

- Constraints on distance learning: some 42 per cent of HHs with school-age children reported that children were unable, or faced difficulties, in participating in distance learning activities. The main difficulties mentioned included electricity cuts, shortage or lack of electronic devices, and limited or no internet connectivity.

- Gaps in access to drinkable water: some 16 per cent of HHs indicated that due to the quarantine they could not secure the minimum of two liters of potable water per day per person. Most piped water in Gaza is unfit for human consumption, requiring families to purchase purified or desalinated water.

- Information on COVID-19: some 95 per cent of HHs said they can access reliable information about the virus in person or via electronic social networks, TV and radio.

In the case of Rana, after a few days in quarantine, she was selected for a psychosocial support programme, and resumed regular contact with some of her teachers via WhatsApp. “One of my teachers taught me how to do deep breathing exercises, which made me feel much better,” she explained.

[1] For an interactive map of isolation and quarantine facilities in Gaza see OCHA’S Website

[2] Information provided by the Ministry of Social Development and the Ministry of Health.

[3] The Gaza ICCG provides a geographically-focused platform for clusters/sectors to work together to jointly deliver an effective and efficient humanitarian response. This is done by reaching a shared understanding of needs, informed by a robust protection and gender analysis, and agreeing on appropriate operational plans to meet those needs.

[4] The sample was selected from a dataset of HHs in home quarantine between 1-20 October provided by the MoSD, which included a total of 2,031 HH, with a margin of error of five per cent. The sampling methodology took into consideration proper representation to all geographical areas, as well as inclusion of male and female-headed HHs.

[5] The mandatory period of quarantine is 14 days after the initial contact with the positive case. The longer period reported by the majority of HHs is attributed to the fact that some family members tested positive after the beginning of the quarantine.

[6] In only 64 of the HHs the member who tested positive was isolated at home, while in the rest of the HHs (180 cases), the member who contracted the virus stayed in an institutional isolation centre and the rest of the family in home quarantine. From early November, after the conduct of the assessment, the relative distribution of positive cases between institutional and home isolation shifted sharply towards the latter.