The humanitarian impact of de facto settlement expansion: the case of Talmon-Nahliel bloc

New research to enhance the humanitarian response and preparedness

The establishment and continuous expansion of settlements, in contravention of international law, is a key driver of humanitarian vulnerability.[17] It has resulted in Palestinians being deprived of their property and sources of livelihood, restricted access to services and has given rise to a range of protection threats that trigger demand for assistance from the humanitarian community.[18]

Research and the monitoring of settlement expansion has focused on the construction of residential areas and has neglected other means of expansion such as road networks and the development of agricultural and tourist sites, mostly on privately-owned Palestinian land, without formal permits, but with the acquiescence of the Israeli authorities (hereafter: de facto expansion). Additionally, while issues such as settler violence and access restrictions to protect settlements are regularly monitored, their relationship to the phenomenon of settlement expansion is often overlooked.

To enhance the humanitarian community’s understanding of these patterns and its ability to respond, OCHA has collected and analysed data on several areas affected in the West Bank.[19] The following case study of Nahliel and Talmon settlements in Ramallah governorate is the second in a series of Humanitarian Bulletin articles on the findings of this research.

The case of Talmon-Nahliel bloc

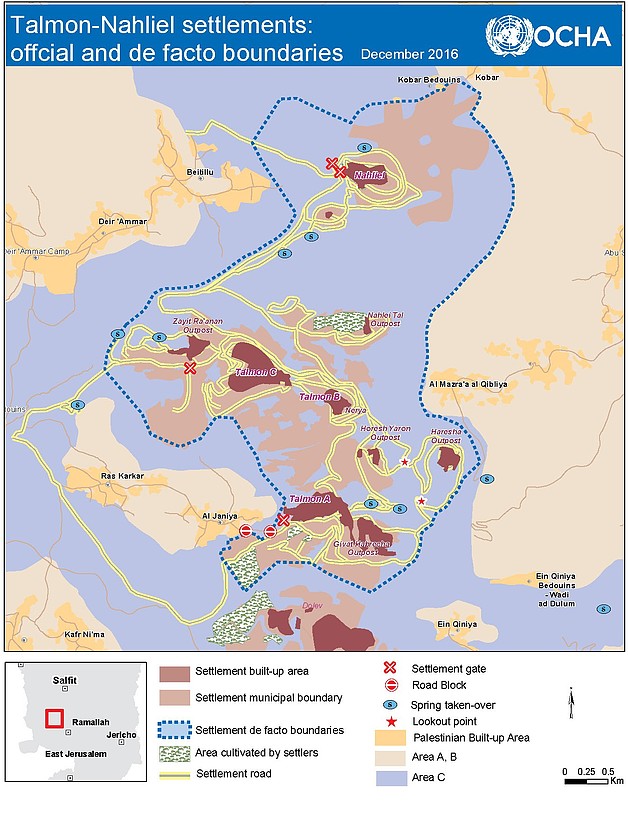

Nahliel and Talmon settlements were established in 1984 and 1989 respectively and have a population of about 4,400. While the official Israeli-designated municipal boundaries of these settlements cover some 6,200 dunums (combined), OCHA’s research found that the area controlled by the settlements and in which Palestinian access is severely restricted or impossible, is almost 2.5 times larger (15,100 dunums).[20] According to Israeli official records,[21] more than half of the land within these de facto boundaries is privately owned by Palestinians from six nearby villages: Beitillu, Ras Karkar, Al Janya, Deir Ammar, Mazra’a Al Qibliya and Kobar, where approximately 20,000 people live.[22]

Expanding a permanent settler presence

Between 1997 and 2002, six new residential settlements, labeled new neighborhoods or outposts, were established on the hilltops surrounding Talmon. All but one (Nerya) were established without a building permit or formal authorization.[23] Despite this, in recent years the Israeli authorities have initiated multiple planning processes to retroactively make these settlements legal under Israeli law. So far, this process has been completed for one of the outposts (Giv’at Habrecha). In the case of the Haresha outpost, the “legalization” process required that 800 dunums of land claimed by Palestinians as their private property be declared as “state land”.[24] In Nahlei Tal outpost, the construction of dozens of permanent housing units is underway even though the relevant planning scheme is yet to be approved and no building permits have been issued. Attempts to establish an additional outpost next to Nahliel settlement were blocked by the Israeli authorities, who dismantled a few temporary structures there. According to Israeli official data, since 2000 the Israeli Civil Administration has issued a total of 293 demolition orders against unauthorized construction in the Talmon-Nahliel controlled area, of which 40 (14 per cent) were executed.[25]

Eight water springs are located within the affected area. These were used in the past by Palestinian farmers and herders for irrigation and the watering of livestock, but have now become largely inaccessible. Five of these springs have been taken over by settlers and developed as tourist sites with the support of government bodies.[26] Similarly, a hilltop next to Haresha outpost, which until the late 1990s was a popular destination for Palestinian pilgrimage (“Sheikh Issa grave”) was also taken over and developed as a tourist lookout point (“Wineries Hill”).

Since 2008, settlers have occupied and begun cultivating, mainly as vineyards, nearly 140 dunums of land, mostly privately owned by Palestinians according to Israeli official records. Additionally, a group of settlers from Nahliel also own a few hundred sheep and goats, which they regularly graze in the valleys between the two settlements.

This de facto expansion has been accompanied and facilitated by the development of an extensive road network connecting the different residential, tourist and agricultural sites. The network extends over almost 60 kilometres and is largely banned for Palestinian use. It includes main roads paved by the Israeli authorities on private Palestinian land requisitioned for “military needs”,[27] as well as dirt roads opened by settlers without official authorization.

Impeding and discouraging Palestinian access

In a series of group discussions conducted by OCHA, residents reported that the regular presence of armed settlers across the affected area, primarily the security coordinators of the settlements and their guards, is intimidating and has discouraged them from accessing their land.[28] The area is also regularly patrolled by Israeli soldiers posted on a military base established next to Talmon in 2005.

The intimidating effect of Israeli armed presence is consolidated by systematic attacks by settlers against farmers and their property. Since 2006, OCHA has documented 14 incidents resulting in Palestinian casualties (one fatality and 23 injuries) and 74 incidents resulting in damage to property, 60 per cent of which entailed uprooting, setting on fire and vandalizing more than 2,200 olive trees. The remaining incidents include theft, damage and arson of agricultural property, and stoning of vehicles and houses. Almost 70 per cent of these incidents (61 incidents) occurred between 2010 and 2013, with a decline recorded in the next three years (19 incidents). These figures exclude the more frequent incidents of harassment, access prevention, and the expulsion of farmers and herders from their land.

Since 2006, there have been at least 11 incidents involving Palestinian attacks against settlers, nine of which involved stone-throwing at vehicles and resulted in seven injuries and damage to vehicles and other property. On 19 June 2015, an Israeli civilian was shot dead by Palestinians while visiting a water spring on Palestinian land adjacent to the Talmon-Nahliel controlled area.

In recent years, Palestinian access to the area controlled by the settlement has been allowed twice a year (during the harvest and ploughing seasons), for two to four days on each occasion and subject to prior coordination with the Israeli authorities. This arrangement applies to six separate areas identified by the Israeli authorities, encompassing some 700 dunums or five per cent of the settlement-controlled area.[29] According to some farmers, this access, albeit very limited, is more predictable than access to privately owned land within the affected area, which is not subject to any formal restriction but involves the threat of systematic intimidation and violence.

Irrespective of the prior coordination, the ability of Palestinian farmers to reach their land is also impeded by physical obstacles deployed by the army or settlers which force them to take long detours. For example, Palestinian access to the main road connecting the two settlements is blocked by a road gate installed in 2003, next to Nahliel main entrance. This gate has remained largely closed despite a commitment by the authorities to open it following a petition to the Israeli High Court of Justice.

Abed al Huda Shreiteh, Mazra’a Al Qibliya

I own 260 dunums of land near the Ein Harasha water spring. One plot of 60 dunums is planted with lemons and oranges and another plot of 200 dunums with olive trees. Since 1986 we have faced difficulties accessing the olive grove, which is adjacent to the settlement outpost of Harasha. We used to make 150 gallons of olive oil but now we make only 20 gallons. In addition, we face settler harassment almost daily. In 2011 a group of Israeli settlers set fire to a house we own on our farm and physically assaulted my son. We have submitted many complaints to the Israeli police and provided them with footage from a video camera provided by the B’Tselem human rights organization, but have not been informed of any outcome.[30]

I own 260 dunums of land near the Ein Harasha water spring. One plot of 60 dunums is planted with lemons and oranges and another plot of 200 dunums with olive trees. Since 1986 we have faced difficulties accessing the olive grove, which is adjacent to the settlement outpost of Harasha. We used to make 150 gallons of olive oil but now we make only 20 gallons. In addition, we face settler harassment almost daily. In 2011 a group of Israeli settlers set fire to a house we own on our farm and physically assaulted my son. We have submitted many complaints to the Israeli police and provided them with footage from a video camera provided by the B’Tselem human rights organization, but have not been informed of any outcome.[30]

Shrinking space, reduced livelihoods

Based on statistics about the scope of land cultivation outside of built up areas in the Ramallah governorate, it is estimated that there are nearly 11,000 dunums of cultivable land within the area controlled by Talmon-Nahliel. Assuming free access were possible, the cultivation of this area along the same models observed in the rest of the governorate (in terms of irrigation and variety of crops), and assuming the same rates of return, would generate an output of approximately $2.3 million a year.[31] This is a conservative estimate based on existing very limited irrigation and excluding other significant income-generating activities such as herding. However, given the severe constraints on Palestinian access to this area, only a tiny portion of this economic potential is being realized.

The six Palestinian communities affected by Talmon-Nahliel de facto expansion face a fragile socio-economic situation:

- The average unemployment rate is approximately 20 per cent, according to estimates by each of the village councils;

- There are 108 families (approx. 550 people) classified as hardship cases and entitled to cash assistance from the Palestinian Ministry of Social Development (MoSD);[32]

- 140 households (approx. 700 individuals) not covered by the MoSD are dependent on food assistance (food rations or vouchers) provided by the UN World Food Programme (WFP).

The restoration of permanent access and security for Palestinians to their land in the settlement-controlled areas would generate much needed livelihood and employment opportunities, and would alleviate the hardship of families affected by unemployment and food insecurity. The return of land to its Palestinian owners and its cultivation would also generate an economic “spillover effect”, with the additional income spent on local goods and services to multiply the impact of the initial growth.

Al Janiya village – coordination difficulties

Abbas Yousef (75), from Al Janiya village, owns 20 dunums of land located inside the fence of Talmon settlement. The land consists of two plots planted with 65 olive trees. According to him, the difficulties in gaining access to this land started in the early 1980s, immediately after the establishment of the settlement.

Until the beginning of the second Intifada in 2000, there was an informal understanding between Al Janiyya farmers and the Israeli authorities to allow Palestinians to access their land near the settlement for a few days a year. This arrangement was suspended completely between 2000 and 2006, during which time most of the trees in this area were reportedly vandalized or uprooted, including 15 of Yousef’s trees. Since 2011, farmers from Al Janiya have been allocated three to four days during the olive harvest season and one to two days during the ploughing season to access their land, following prior coordination with the Israeli authorities. The latter prevent some farmers from using tractors to plough their land, citing potential damage to the settlement’s sewage network.

In addition to the loss of 15 yielding trees, Yousef reports that the 50 olive trees that currently remain in this area yield an average of 10 gallons of olive oil per season, generating an income of approximately US$1,000, down from 30 gallons generating US$3,000 prior to 2000.

[17] Since 1967, about 250 Israeli settlements and settlement outposts have been established across the occupied West Bank, including East Jerusalem. This violates Article 49 of the Fourth Geneva Convention, which prohibits the transfer by the occupying power of its own civilian population into the territory it occupies. This has been confirmed numerous times, among others by the International Court of Justice (Advisory Opinion on the Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory of 9 July 2004); the High Contracting Parties to the Fourth Geneva Convention (Declaration from 5 December 2001); the United Nations Security Council (Resolution 471); and the United Nations General Assembly (Resolutions 3092 (XXVIII), 47/172 and 66/225).

[18] For an overview of the humanitarian responses to settlement activities proposed by humanitarian agencies operating in the occupied Palestinian territory in 2016, see Humanitarian Country Team, Strategic Response Plan 2016.

[19] Cases were selected to represent different geographical areas of the West Bank, and the extent to which settlement activities in each of the selected cases has received attention from humanitarian actors.

[20] This finding is based on a series of focus group discussions with residents of affected neighbouring Palestinian communities, supplemented with dozens of visits and analysis of aerial pictures of the area since the late 1980s that reveal trends in cultivation, the development of built-up areas, appearance of new roads, etc.

[21] Calculation based on a GIS layer obtained from the Israeli Civil Administration (ICA) marking the status of the land in the affected area as either privately-owned or public (also known as “state”) land.

[22] Due to the unavailability of PCBS data for 2014, the population of three of the affected communities (Beitillu, Deir Ammar and Mazra’a Al Qibliya) was estimated based on 2007 data and updated by the rate of growth for Ramallah governorate as a whole.

[23] The settlement established with official authorization was called Nerya. The other five are: Horesh Yaron, Zait Ra’anan, Haresha, Nahlei Tal and Givat Habrecha. The latter outpost was “legalized” retroactively under Israeli law in 2011 after a petition filed by residents of Al Janyia to the Israeli High Court of Justice was rejected.

[24] A petition against this declaration was filed by the Palestinian owners with the Israeli High Court of Justice and is still pending.

[25] GIS layer provided by the ICA to the Israeli NGO, Bimkom, following an information request under the Freedom of Information Act. Demolition orders executed include structures removed by their owners.

[26] The Mate Binyamin Regional Council, to which both settlements belong, has a dedicated webpage (in Hebrew) promoting tourism in the area, including the five springs. See here.

[27] This is the case with the main road linking Nahliel and Talmon. This is one of the bypass roads planned in the IDF redeployment as part of the Oslo Interim Agreement and the handover of areas to the Palestinian Authority. Seizure order 28/95 issued on 17 September 1995.Another major route opened in 2002 and connects three of Talmon’s outposts to the main bypass road leading westwards into Israel (Road 463).

[28] Military orders define five separate ‘guarding areas’ covering nearly 2,800 dunums where security coordinators are authorized to operate. In practice, the area of operation of these armed settlers is defined by the de facto boundaries. The IDF is formally responsible for arming, training and supervising the work of security coordinators who are accountable to the municipal bodies of the settlement that appoint them and pay their salaries, often creating a conflict of interests. For further background on the issue, see Yesh Din, The Lawless Zone, June 2014.

[29] According to official maps issued by the Israeli Civil Administration in 2014.

[30] Testimonies collected in January 2014.

[31] Agricultural economic potential was estimated by FAO on the basis of data provided by OCHA on the size of the areas affected and by PCBS (2007/8) on cultivation patterns in Nablus governorate.

[32] Allocations range from NIS 750-1,800 every three months depending on the severity of the case.