The humanitarian impact of de facto settlement expansion: common features, conclusions and the way forward

New research to improve humanitarian responses and preparedness

The establishment and continuous expansion of settlements, in contravention of international law, is a key driver of humanitarian vulnerability.[1] Settlements have deprived Palestinians of their property and sources of livelihood, restricted their access to services and given rise to a range of threats that trigger demand for protection and assistance from the humanitarian community.

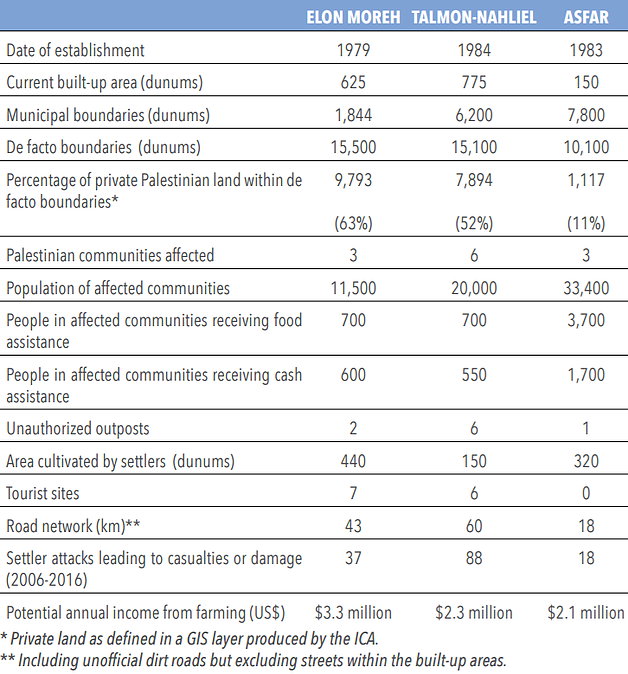

To enhance the humanitarian community’s understanding of patterns of settlement expansion which have been relatively neglected, and to improve the ability to respond, OCHA has collected and analyzed data on the de facto expansion of three settlement areas: Asfar in Hebron governorate; Talmon and Nahliel in Ramallah governorate; and Elon Moreh in Nablus governorate.[2] The past three Humanitarian Bulletins have focused on these cases. The following article, which is the fourth and last in this series, presents some common features, conclusions and recommendations.

The three cases highlighted in this study describe the ongoing efforts by Israeli settlers to increase their spatial control over surrounding areas and natural resources through the development of new infrastructure and activities, alongside attempts to remove a Palestinian presence (see key indicators table).[3]

Modalities of expansion

The main modalities used by settler groups to consolidate their presence across the affected areas, typically with the support of the settlements’ municipal authorities, include the erection of residential outposts; the development of tourist sites (primarily lookout points and water springs used as recreational sites); and the cultivation of de facto annexed land.[4] Settler groups and local bodies enhance this process by creating an extensive road network connecting such sites to the settlement’s residential core. Other roads serve to demarcate key sections of the de facto boundaries.

The bulk of these activities lack official authorization from the Israeli authorities. In most cases this is due to the status of the lands in question, which are mainly classified as private Palestinian property. Despite the absence of official approval, much of this expansion has taken place with the acquiescence, and at times the active support, of the Israeli authorities. This is reflected in planning and building policies where violations of the relevant laws and regulations are either ignored or only enforced to a limited extent. Instances of active support include the direct funding of unauthorized activities by state institutions such as regional councils and the Settlement Division of the World Zionist Organization. Consistent state support to settlements established on private Palestinian land was explicitly acknowledged in the explanatory notes to the “Regularization Law” adopted by the Israeli parliament in January 2017. [5]

Discouraging Palestinian access

The consolidation of a settler presence across these areas is enabled and facilitated by practices implemented concurrently by both settlers and Israeli forces to impede and discourage Palestinian access. These include various types of access restriction: the deployment of roadblocks and checkpoints; prohibition on the use of roads by Palestinian vehicles; the designation of areas as closed for military purposes or as “nature reserves”; the fencing off of privately-owned Palestinian land; and making Palestinian access to farming land subject to a “prior coordination” system.

Other practices involve intimidation by regular patrolling of the affected area by soldiers and armed settlers. The former are often stationed in military bases located within the settlement’s residential area with the stated goal of securing the area, while the latter primarily comprise the security coordinators and guards of the settlements, usually settlement residents who hold policing powers enshrined in military legislation.

Access restrictions often followed violent attacks by Palestinians, including the killing of Israeli settlers, and have been justified by settlers and/or the Israeli authorities as security measures to prevent the recurrence of attacks.

There are also direct attacks by settlers, which typically include physical assault, stone throwing, uprooting of trees, and setting fire to crops and equipment. While the frequency and location of attacks varies, the fear generated is often long-lasting. Law enforcement against violent settlers has been lax and the vast majority of attacks go unpunished.[6] Since 2014 the number of settler attacks has declined, possibly due to preventive measures adopted by the Israeli authorities, including increased deployment of forces in sensitive areas.

The temporal and geographical proximity between these violent attacks and takeover of new areas suggests that settler violence against Palestinians is not random but is often a calculated step towards settlement expansion.

Settler violence and intimidation have triggered protection-related interventions by humanitarian and human rights organizations, including a protective presence, primarily during the olive harvest season; the documentation of cases and pursuit of accountability; and the provision of psychosocial support to victims.

These powerful “push factors” are counter-balanced to a certain extent by “pull factors”: the strong attachment of Palestinian farmers to their land, and legal recourse against denial of access and dispossession. Supported by human rights and humanitarian organizations, some farmers have maintained or regained limited access to farming land absorbed within the settlements’ de facto boundaries. However, access is only permitted twice a year during the ploughing and harvest seasons, for two to three days each time, and only following prior coordination with the Israeli authorities.

Impact on livelihoods

The humanitarian impact on the Palestinian population needs to be assessed holistically and over a significant period of time. The immediate impact of settler attacks may be limited (e.g. cutting branches of olive trees), but when combined with other factors (e.g. movement restrictions by Israeli forces, loss of access to water sources and systematic intimidation by armed settlers) may trigger a halt in cultivation that can have a long-term impact on a family’s living conditions.

Farming and grazing are traditional sources of livelihood for all the communities covered in this study. Loss of access to land due to de facto settlement expansion has had a major impact on the living conditions and food security of affected families; some have reported a change in diet because food items previously self-produced need to be purchased at market prices. Additional impacts may include the loss of access to water springs, previously used for irrigation and watering of livestock, as well as spaces that served for leisure and recreation.

This situation has prompted various humanitarian interventions, including cash assistance by the Palestinian Ministry of Social Development to families newly identified as “hardship cases”; food assistance (in-kind or vouchers) by UN agencies to food insecure households; and agricultural support by local and international and national NGOs in the form of land reclamation and water harvesting projects.

Key indicators of three case studies

The way forward

Humanitarian and human rights organizations can improve their support to Palestinian communities affected by de facto settlement expansion and mitigate the humanitarian impact of this phenomenon by:

- Developing early warning systems of humanitarian vulnerability to identify areas at risk of takeover by Israeli settlers.

- Expanding legal support to farmers facing access restrictions or denied access to their land.

- Providing technical support and/or financial subsidies to resume land cultivation.

- Deploying observers/companions as a protective presence for farmers accessing their land within settlement affected areas.

- Increasing engagement with the Israeli authorities to prevent the takeover of additional areas and to secure Palestinian access to areas affected by settler violence.

[1] Since 1967, about 250 Israeli settlements and settlement outposts have been established across the occupied West Bank, including East Jerusalem. This violates Article 49 of the Fourth Geneva Convention, which prohibits the transfer by the occupying power of its own civilian population into the territory it occupies. This has been confirmed numerous times, among others by the International Court of Justice (Advisory Opinion on the Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory of 9 July 2004); the High Contracting Parties to the Fourth Geneva Convention (Declaration from 5 December 2001); and the United Nations Security Council (Resolutions 471 of 1980 and 2334 of 2016).

[2] Cases were selected to represent different geographical areas of the West Bank and the extent to which settlement activities in each of the cases has been addressed by humanitarian actors.

[3] While the facts and figures presented in this report refer only to the three cases examined, during the preliminary stage of this research (case selection), OCHA has collected evidence suggesting that the phenomenon of informal settlement expansion is widespread. Similar patterns to those documented in these three case studies were identified in another eight settlement areas: Eli-Shilo bloc (Nablus); Kochav Hashachar (Ramallah); Ma’ale Michmash (Ramallah); Bracha (Nablus); Ofra (Ramallah); Bat Ayin (Bethlehem); Teqoa-Noqedim bloc (Bethlehem); and Susiya (Hebron). The specific distribution of these cases suggests that the geographical focus of this phenomenon is the central West Bank mountain ridge, rather than the western strip close to the Green Line or the Jordan Valley.

[4] These residential and tourist sites are usually located on high elevation points to allow for an overview of the surrounding areas.

[5] This law allows the expropriation of land taken over with the support of the state. This phenomenon was previously documented by a fact-finding committee on the question of settlement outposts appointed by the Government of Israel (also known as the Sasson Committee after its chair Talia Sasson), which published its conclusion in 2005. See: Opinion Concerning Unauthorized Outposts.

[6] For a comprehensive review of this phenomenon see: Yesh Din, A Semblance of Law, June 2006; Yesh Din, Data Sheet, October 2015.