Large area in Bethlehem declared ‘State Land’

Based on past experience, the area is expected to be allocated for settlement development

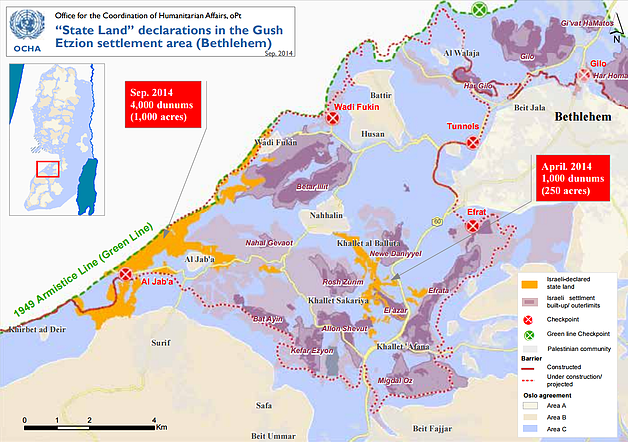

On 25 August, the Israeli Civil Administration (ICA) announced the declaration of 3,799 dunums of land (1 dunum = 1000 m2) in Bethlehem governorate as ‘state land’. This follows a case earlier this year, on 6 April 2014, in which the ICA had declared 1,000 dunums of land in Area C, also in Bethlehem governorate, to be ‘state land’.[1] According to the Israeli media, this measure was approved by the Israeli cabinet in response to the kidnapping and killing of three Israeli youths in June.

The affected areas are adjacent to the Green Line and lie within the boundaries of Surif, Nahhalin, Husan, Al Jab’a and Wadi Fukin villages. People claiming private ownership of the land were given 45 days to submit an appeal before a military committee.

Once the process is complete, the area is expected to be officially incorporated within the boundaries of the Gush Etzion Regional Council. The head of the Council told the Israeli media that the recent declaration paves the way for the development of a new city in Gush Etzion, to be called Geva’ot.[2]

While this procedure served in the past as the main tool for the seizure of land for the establishment of settlements, its use has been largely discontinued since the early 1990s. Hence, the resumption of this practice and the large size of the area affected may indicate a broader policy change.

The UN Secretary-General has called previously on Israel to cease the allocation of state land for the establishment and expansion of settlements.[3] On 1 September, the spokesman for the UN Secretary-General stated that: “The seizure of such large swathes of land risks paving the way for further settlement activity, which- as the United Nations has reiterated on many occasions- is illegal under international law and runs totally counter to the pursuit of a two-state solution.”

Following a landmark ruling by the Israeli Supreme Court in 1979 (the Elon Moreh case) forbidding the allocation of land requisitioned for military purposes for the establishment of settlements, the Israeli authorities developed a new policy based on an interpretation of the Ottoman Land Code of 1858.[4] Despite many amendments introduced since, the Code has remained in force as the main source of rules regulating land rights in the West Bank.

The new policy builds on a provision in the Code stipulating that the state may take possession of land that is not cultivated for three consecutive years and declare it to be ‘state land’. The policy includes a new and restrictive interpretation of what constitutes ‘cultivation’ for the purposes of the Code, as well as a range of bureaucratic and legal hurdles undermining the ability of Palestinians to effectively challenge such land seizures.

According to Israeli official data, over 99 percent of all state land in Area C has been included within the jurisdictional boundaries of Israeli settlements (local and regional councils) and subsequently allocated for settlement development, military training or nature reserves.[5]

Under international humanitarian law (IHL), public property in an occupied territory should be administered primarily for the benefit of the local population. The allocation of land for settlement building and future expansion runs contrary to this principle and has resulted in the shrinking of space available for Palestinians to develop adequate housing, basic infrastructure and services, and to sustain their livelihoods.

The Barrier: 10th Anniversary of the International Court of Justice’s Advisory Opinion

9 July 2014 marked the 10th anniversary of the International Court of Justice’s (ICJ) Advisory opinion on the Legal Consequences of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory. The Advisory Opinion called on Israel to cease construction of the Barrier ‘including in and around East Jerusalem’; dismantle the sections already completed; and ‘repeal or render ineffective forthwith all legislative and regulatory acts relating thereto.’ Israel is also under an obligation to make reparation for all damage caused by the construction of the wall. All States are under an obligation not to recognize the illegal situation resulting from the construction of the wall and not to render aid or assistance in maintaining the situation created by such construction

9 July 2014 marked the 10th anniversary of the International Court of Justice’s (ICJ) Advisory opinion on the Legal Consequences of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory. The Advisory Opinion called on Israel to cease construction of the Barrier ‘including in and around East Jerusalem’; dismantle the sections already completed; and ‘repeal or render ineffective forthwith all legislative and regulatory acts relating thereto.’ Israel is also under an obligation to make reparation for all damage caused by the construction of the wall. All States are under an obligation not to recognize the illegal situation resulting from the construction of the wall and not to render aid or assistance in maintaining the situation created by such construction

To mark the occasion, on 8 July, a Humanitarian Country Team event led by UNRWA took place in Al-Walaja village, including a field visit for donors, diplomats and media, presentations by the Humanitarian Coordinator, UNRWA and OCHA, as well as an iftar (Ramadan) meal with community members. On the same day, OCHA released an expanded infographic, ‘In the Spotlight: 10 years since the ICJ Advisory Opinion’ featuring comprehensive information on the Barrier and its humanitarian impact in the West Bank. Click here to access.

[1] OCHA, Humanitarian Bulletin, April 2014.

[2] H. Levinson, Ha’aretz, 30 September 2014.

[3] See A/68/513, para. 56. Also see A/69/150.

[4] For further details see, B’Tselem, Under the Guise of Legality - Declarations on State Land in the West Bank, March 2012, A/68/513, para. 17 to 22.

[5] Data provided by the ICA to Bimkom, Planners for Planning Rights, in the context of an information request under the Freedom of Information Act.