Longstanding access restrictions continue to undermine the living conditions of West Bank Palestinians

To contain the spread of COVID-19, governments around the world have imposed sweeping restrictions on the freedom of movement of people, severely disrupting their lives. While the occupied Palestinian territory (OPT) is no exception, with measures being imposed by both Israeli and Palestinian authorities, these have served to exacerbate longstanding access restrictions that are imposed by the Israeli authorities.

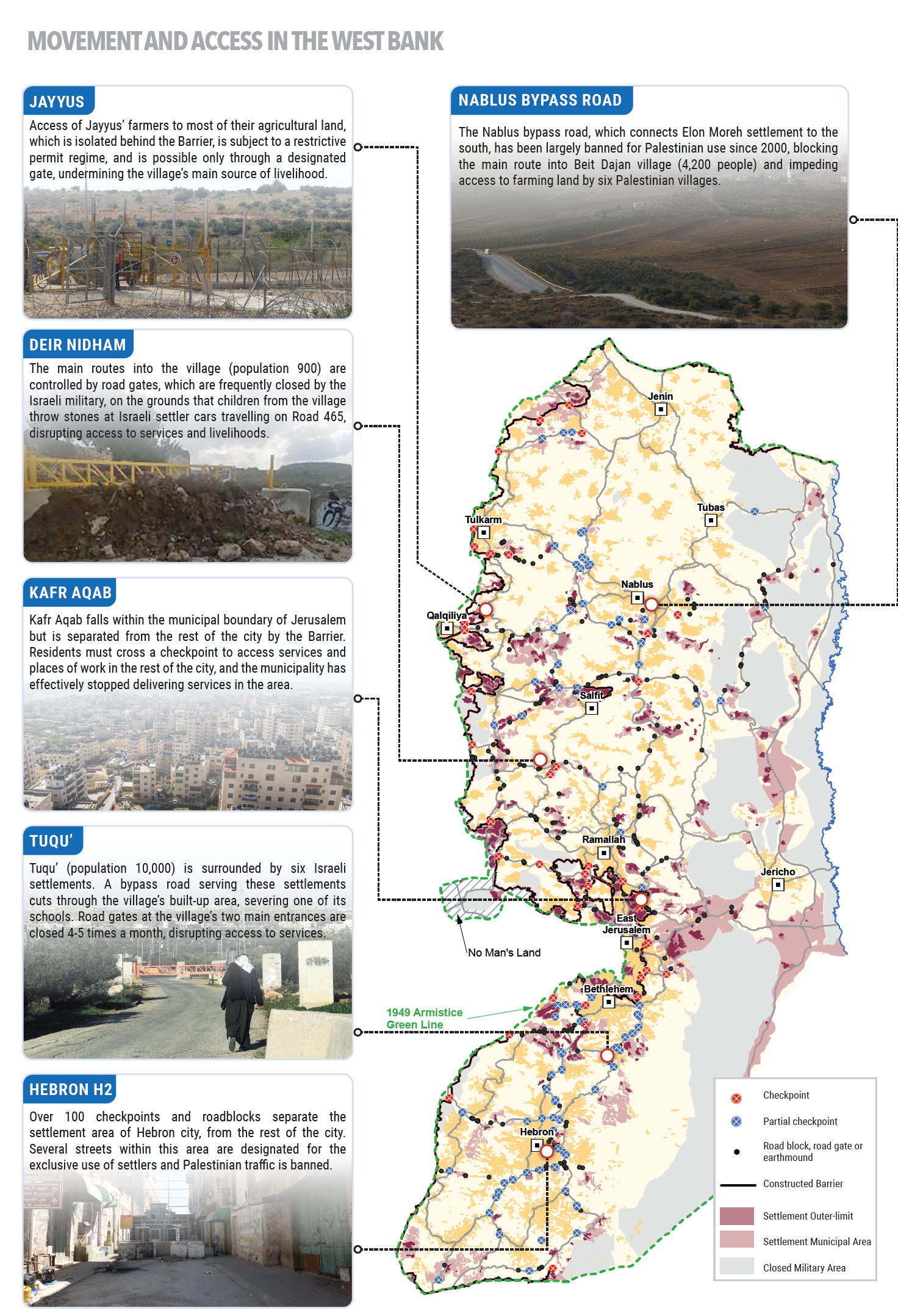

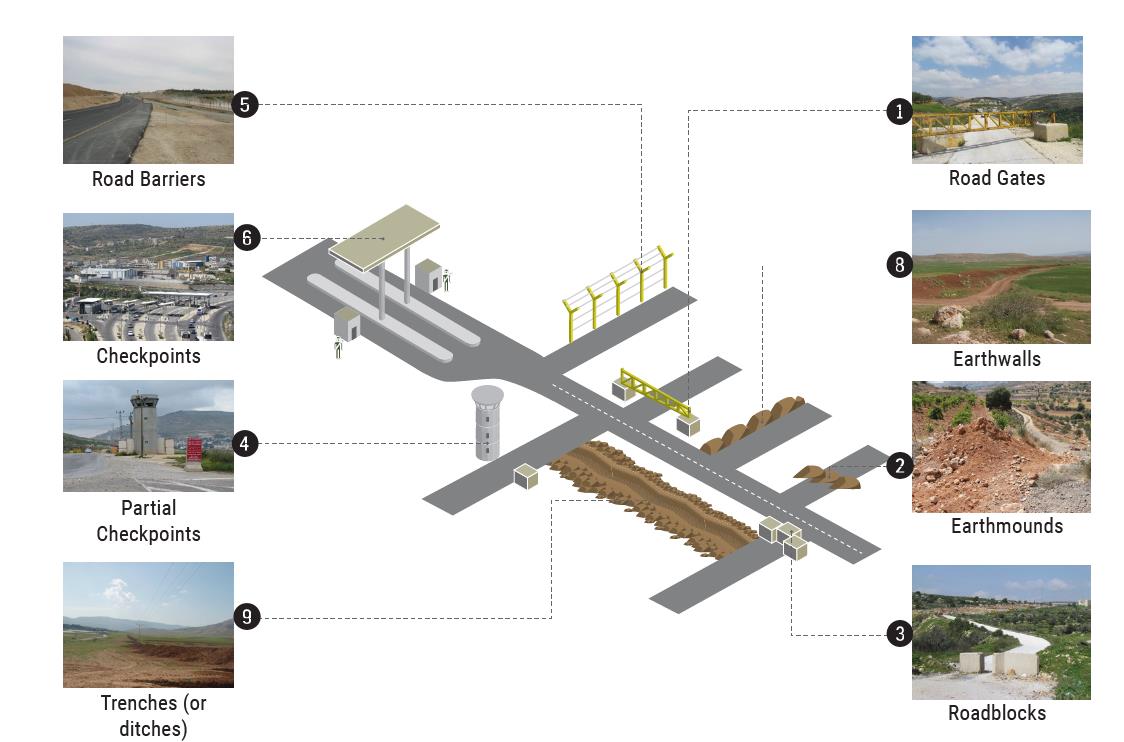

Within the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, Palestinian movement is restricted by a multi-layered system of physical and administrative measures. These comprise physical obstacles, including checkpoints; bureaucratic and administrative requirements, such as permits; and the designation of areas as restricted or closed, including “firing zones.” To varying degrees, these movement restrictions impede access to services and resources; disrupt family and social life; undermine livelihoods; and hinder the ability of humanitarian organizations to deliver assistance.

Many of these restrictions have been justified by the Israeli authorities as means to address security concerns, which often include the protection of settlements established across the West Bank, in contravention of international law.

Over the past two decades, the Israeli authorities have developed a secondary road network serving Palestinians, including some 50 tunnels and underpasses, which have re-connected Palestinian localities severed by obstacles, and eased the impact of some of the movement restrictions. However, the development of this network has required the expropriation of private and public Palestinian property and constrained spatial planning, while contributing to the fragmentation of the West Bank.

This article presents the findings of the latest movement obstacle survey and highlights the impact of access restrictions on a Palestinian community in western Ramallah, and on farmers owning land cut off the West Bank Barrier. It is the first in a series of articles focussing on the humanitarian impact of access restrictions in the West Bank.

Sixteen per cent decrease in movement obstacles

For the past 15 years, OCHA has been regularly mapping the physical obstacles affecting Palestinian movement within the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, with the purpose of identifying their humanitarian consequences and facilitating a coordinated response to them.

The latest comprehensive survey was conducted in January-February 2020. The findings showed a 16 per cent decrease in the overall number of fixed permanent obstacles (checkpoints, earthmounds, road gates, etc) compared with the previous survey in July 2018: from 705 to 593 obstacles.

Details about these obstacles, including a brief description and a photo of each, are available on an interactive mapping platform in OCHA’s website.

About 70 per cent of the decrease since the previous survey (79 out of 112) was due to OCHA’s removal from the list of obstacles identified as having a ‘negligible impact’ on people’s movement, following a comprehensive review of the data collected. These include, mostly, obstacles blocking routes for which an alternative route of similar length was opened; or earth-mounds that have been flattened, allowing for the passage of vehicles over them.

The survey confirmed the trend observed in recent years, of replacing fixed obstacles, such as roadblocks and earth-mounds, with ‘flexible’ ones, such as partial checkpoints and road gates that for the most part remain open, but can be closed at any time. Partial checkpoints are only occasionally staffed or have security personnel located in a tower, rather than on the ground. The survey identified a total of 108 such checkpoints, an increase from 73 from the previous survey. Over the course of the past year (April 2019- March 2020), OCHA documented 1,064 occasions in which partial checkpoints were staffed and personnel carried out checks on the ground.[1] Additionally, a total of 154 road gates were identified in the survey, which can be opened and closed at any time based on criteria established by military commanders. Combined, partial checkpoints and road gates accounted for about half of all the obstacles mapped.

This trend of using more ‘flexible’ obstacles is also consistent with the frequent deployment of temporary, ad-hoc ‘flying’ checkpoints (not included in the count) on key routes for several hours each time. Over the same 12-month period, Israeli forces deployed over 1,500 such checkpoints.[2]

The shift has resulted in a less disruptive impact on the daily life of Palestinians. These obstacles form part of a system of control, which allows a relatively smooth movement of persons and vehicles, while still retaining the capacity to rapidly lock down a given area, based upon the decision of a military commander (see case study on Deir Nidham village).

There are significant exceptions to this trend, however. In East Jerusalem and in those parts of the West Bank, where Palestinian land is cut off by the Barrier, access is still controlled by means of permanently-staffed checkpoints and by long-standing permit requirements.

Permanently-staffed obstacles also predominate in most of the Israeli-controlled area of Hebron city (H2), which is separated from the rest of the city by 101 obstacles (or 17 per cent of all obstacles), including 32 checkpoints. Palestinian vehicular movement within H2 is severely restricted; in certain areas, pedestrian access also is restricted only to residents.[3] Over the past year, however, the Israeli authorities have eased some of these restrictions, including occasionally opening some road gates, and also granting special permits so that some few dozen families can now access their homes by car.

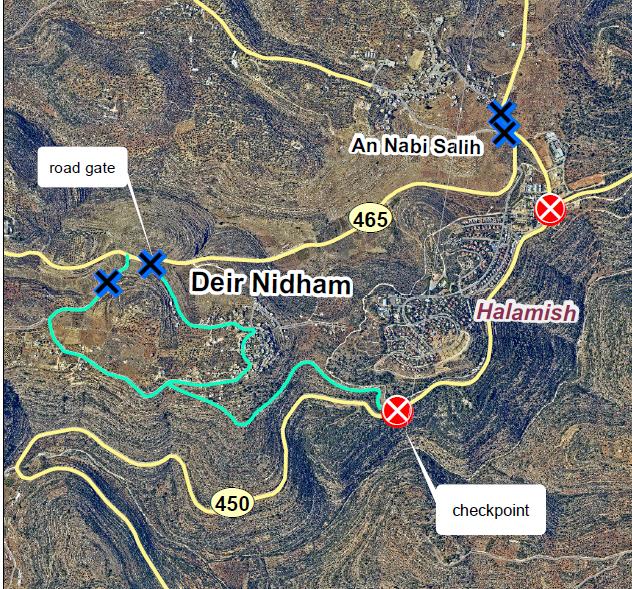

Closure of village entrances: The case of Deir Nidham

One of the purposes of deploying ‘flexible’ obstacles is to block one or more of the main entries to communities where the perpetrators, or alleged perpetrators, of attacks against Israelis reside, or from where stone or Molotov cocktails are regularly thrown at Israeli vehicles. These occurrences vary in their severity (from a total closure to strict checks on vehicles) and may last from a few days to a number of weeks, with residents forced to cross obstacles on foot, or to resort to detours.

Deir Nidham (population 900) is one of 11 villages in the western Ramallah governorate and is adjacent to the Israeli settlement of Halamish. There are three routes into the village: one of them, via Road 450, runs along the settlement, and necessitates crossing a checkpoint, while the other two entail passing through a road gate (see Map). These gates are frequently closed by the Israeli military, on the grounds that children from the village throw stones at Israeli settler cars travelling on Road 465. Deir Nidham has also experienced in a high rate of search-and-arrest operations, with Israeli forces conducting 24 operations in 2019, arresting 39 Palestinians, more than half children.

Muneer Hasan Tamimi, a father of four, is a resident of the nearby An Nabi Saleh village. “My eldest son, Mohammed, who’s 16, attends high school in Deir Nidham, which is a few kilometers south of An Nabi Saleh. He goes there every morning, accompanied by a teacher from our village who teaches at the school. Even when the gates on the road leading to the village are open, access is unpredictable, since they’re often staffed by soldiers, who question and search my son. This leads to long delays, where Mohammed misses class. He usually walks the four kilometers back home, when no one is available to give him a lift: I worry about him, walking along the road and having to pass through the gate on his own.’’

Search-and-arrest operations also intensified in the first two months of 2020, with 14 incidents recorded, more than of half of the total in 2019.

“Since the beginning of this year, Mohammed has stayed home for almost a month because Deir Nidham has been completely closed off. I’ve tried to arrange for private tutors, but I cannot afford that”, Muneer Tamimi added.

In addition to the students and teachers who commute on a daily basis from neighboring villages, the closure of the gates also disrupts the access of the residents of Deir Nidham to health services and livelihoods, with a disproportionate impact on children, the elderly and disabled people. Shops and businesses that are the main source of income for the community, are affected by the diversion of Palestinian traffic away from the village in general. Family life has also been affected by the unpredictable nature of the closures, discouraging visitors from visiting the community.

The Barrier remains the main physical obstacle to Palestinian movement in the West Bank

The physical obstacle survey undertaken by OCHA does not include the restrictions associated with the Barrier, which remains the main obstacle to Palestinian movement within the West Bank, including East Jerusalem. Most Palestinian farmers must obtain special permits from the Israeli authorities to access their farmland in the the area between the Barrier and the Green Line, or “Seam Zone”; this requirement also applies to family members and to agricultural workers.[4] Recent years have witnessed a significant decline in the allocation of these permits, while new standing regulations, issued in September 2019, set a limit on the number of days that farmers can access their land over the course of a year, based on the size of the plot and the nature of the crop.[5]

If permits are granted, access is channelled through designated gates. During the 2019 olive harvest, OCHA recorded 74 gates and five checkpoints which were designated for agricultural access. Of these, only 11 open daily, ten open for some day(s) of the week and during the olive season, and the majority, 53, only open during the olive season.

Recently, as a result of new measures introduced in the context of the COVID-19 emergency, Palestinian access to land behind the Barrier has been further restricted. Field reports indicate that the Israeli authorities have suspended most existing permits in the Jenin, Tulkarm, Qalqiliya and Salfit governorates. These districts account for most Palestinian agricultural output in the ‘Seam Zone’, because of the cultivation of crops and cereals in addition to with olive trees, and the especially intrusive nature of the Barrier in the area. On 4 May, the Israeli human rights organization, HaMoked sent an urgent letter to the head of the Civil Administration, demanding that the military disclose its official policy on access to the ‘Seam Zone’ during the COVID-19 crisis; the immediate reinstatement of permits, should they be frozen; as well as the reopening of all gates that have been arbitrarily closed.[6]

Since early May, Palestinian farmers who own land in the ‘Seam Zone’ in the Qalqiliya area have been permitted to regain access to this land. However, access remains restricted in the Jenin, Tulkarm and Salfit governorates, due to the continuing revocation of permits and the non-opening of agricultural gates.

Personal Story: “I couldn’t harvest my tobacco crop because I didn’t get permits for my workers”

According to Tayseer, “even though I was the only lucky person from Akkaba to be granted a permit for that whole month, I wasn’t able to harvest my tobacco crop because I didn’t manage to get a permit for my workers. The situation is particularly frustrating, because Palestinian labourers in Israel are sneaking back and forth through holes cut in the Barrier; there are at least five of these holes around Akkaba. At the same time, we can’t get permits for ourselves, our families, or workers just to get to our land in the West Bank! Even before the new restrictions, there were many farmers in Akkaba who didn’t manage to get their permits renewed this year, since they started linking permits to the size of the plot of land and then limiting the number of entries per permit.”

Eventually, I hired new workers and pay them double the normal wage. That’s the only way I was able to save some of my tobacco crop. Others weren’t so lucky. I know four famers who didn’t get permits because of the new restrictions and they lost their onions harvest, which is worth about 2,000 NIS per dunum.”

The way forward

Under international humanitarian and human rights law, Israel must ensure the free movement of Palestinians within the OPT, including East Jerusalem, and enable them to exercise the full range of human rights dependent on such movement, particularly the right to health, to education and to an adequate standard of living. Exceptions to this obligation are allowed only for imperative security or public health reasons, such as the current pandemic; additionally, they must not entail discrimination on prohibited grounds, disproportionately harm other human rights or constitute collective punishment.[7]

As recorded in OCHA’s survey, over the past year, the Israeli authorities have eased some restrictions on the freedom of movement of Palestinians, including by removing certain physical obstacles and the replacement of “rigid” obstacles with more “flexible” ones, which can be kept open. However, the Israeli authorities must do more to ensure that existing obstacles, which do not meet international law requirements, are either removed or opened.

In particular, the authorities must avoid the closure of entire Palestinian villages following attacks against Israelis, unless imperatively demanded for security reasons; as highlighted by the UN Secretary General in 2017, this measure “may amount to collective punishment,” which is absolutely prohibited under international law.[8]

Finally, as stated by the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in its 2004 Advisory Opinion, Israel must dismantle those sections of the Barrier which run inside the West Bank, including East Jerusalem. In the meantime, the associated gate and permit regime must be revoked, to allow Palestinians free access to their land in the ‘Seam Zone’.

[1] Although this figure is based on information provided by a wide network of key informants, it is believed to be an underestimate.

[2] Ibid.

[3] For an overview of the situation in the H2 area see, OCHA, Dignity denied: Life in the settlement area of Hebron city, The Humanitarian Bulletin, January-February 2020.

[4] In certain areas, Palestinians can access the closed area by means of prior approval from the Israeli authorities, referred to as ‘prior coordination’.

[5] According to official data obtained by the Israeli organization HaMoked, the approval rate for permits for landowners fell from 76 per cent of applications in 2014 to 28 per cent in 2018 (up to 25 November). Permits issued to agricultural workers declined from 70 per cent to 50 per cent of applications in the same period.

[6] HaMoked to the military: permit holders must be allowed to enter and exit the Seam Zone unless under legal restrictions.

[7] The right to freedom of movement within a territory where a person is lawfully staying, is enshrined in a number of human rights treaties to which Israel is a signatory, and apply in the OPT, including Article 12 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

[8] Report by the Secretary General, Human rights situation in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including East Jerusalem, A/HRC/34/38, April 2017, para. 32-33,

[9] OCHA, Record yield reported from 2019 olive harvest, The Humanitarian Bulletin, January-February 2020.