Movement restrictions on West Bank roads tightened

OCHA survey: 20 per cent increase in closure obstacles

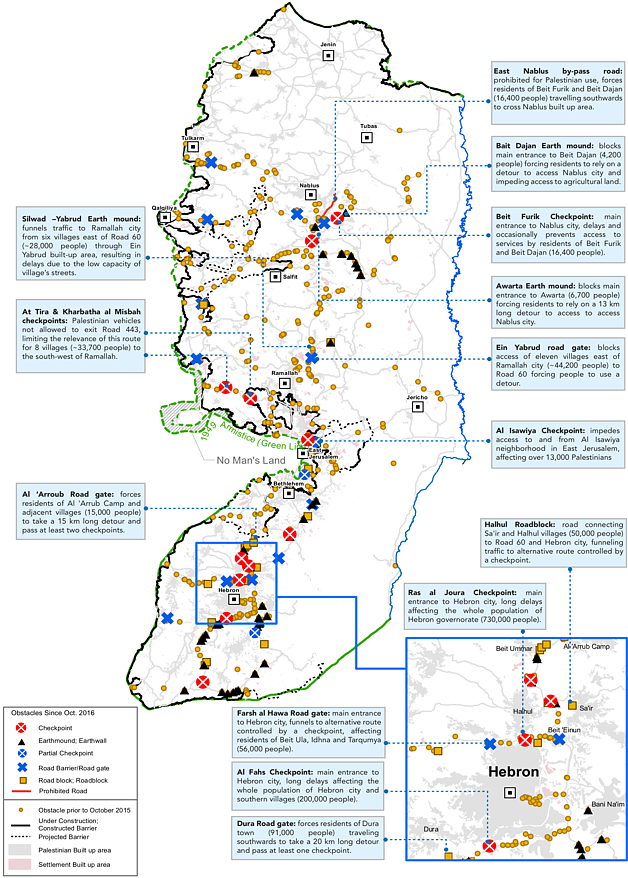

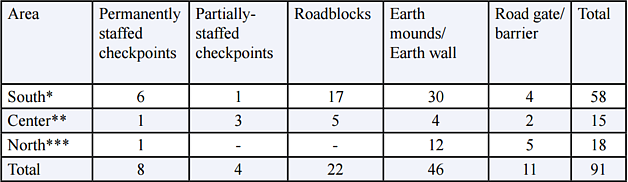

A rapid survey carried out by OCHA during the last week of 2015 found that since the escalation in violence in October 2015, Israeli security forces have deployed 91 new obstacles (checkpoints, roadblocks, earth mounds, etc.) on West Bank roads to restrict Palestinian vehicular movement. This figure includes only those obstacles involving some kind of fixed infrastructure on the ground, thus excluding ad-hoc “flying” checkpoints (see table and map below). These obstacles are in addition to 452 pre-existing obstacles, representing a 20 per cent increase in their overall number.

The majority of the new obstacles are not staffed (roadblocks, earth mounds and road gates) and are located on secondary routes connecting Palestinian communities to main roads used by Israelis, primarily settlers. These obstacles funnel Palestinian traffic into a limited number of junctions, usually controlled by checkpoints staffed by Israeli forces. Depending on the level of tension in a particular area, the latter stop Palestinian vehicles, and in some cases pedestrians, to carry out checks and searches.

The detours required to reach accessible junctions and the prolonged delays (up to several hours in some cases) at checkpoints have impeded the access of people to services and undermined economic activity. The new closures directly impact, to various degrees, at least 850,000 Palestinians, the vast majority in Hebron governorate.

The new checkpoints further increase friction between Palestinians and Israeli forces. Some of these locations have repeatedly been targets of attack (mostly stabbing) or alleged attacks against soldiers, usually concluding in the killing of the Palestinian perpetrator or suspected perpetrator. The Beit Einoun checkpoint in Hebron governorate, for example, witnessed seven such attacks and alleged attacks, resulting in six Palestinian fatalities and five Israeli injuries.

New physical obstacles on West Bank roads since Oct. 2015 (up to end of 2015)

Although the situation has remained volatile, restrictions were eased slightly during January 2016, including throughout Hebron governorate. This is seen in the partial staffing of the some of the new checkpoints and fewer checks and searches at others, thereby reducing delays and travelling times. In East Jerusalem, the majority of obstacles deployed following the escalation in violence were removed over the course of November and December 2015, prior to the OCHA survey, and only nine (out of 42) remain in place.

Movement obstacles as of 31 December 2015 selected impacts

Hebron: the most affected governorate

Approximately 57 per cent of the obstacles installed since October 2015 are in the Hebron governorate, making it the most affected area. A large part of the negative impact of the new closures stemmed from the reduced connectivity between Hebron city, which functions as a regional hub for services and economic activity, and the towns and villages across the governorate. As of the end of January 2016, however, the situation at most of the main entrances to the city went back to normal, with new checkpoints being only occasionally staffed. By contrast, there has been no relaxation of restrictions on Palestinian access to and within the Israeli controlled part of the city (see November Humanitarian Bulletin).

Delays in transferring urgent medical cases to hospitals in Hebron city is a concern, particularly for patients travelling in private vehicles. In the last three months of 2015, the Palestinian Red Crescent Society (PRCS) documented 12 incidents of serious delays undergone by ambulances at Hebron checkpoints. The restrictions have also disrupted the delivery of regular medical services to hospitals and clinics: the Ministry of Health clinics in Ad Dahiriya, As Samu, Arihiyah, Beit Awwa, and Deir Samit were particularly affected.

The Hebron Chamber of Commerce and Industry estimate losses of over NIS2.5 billion (approximately $633 million) as a result of the decline in economic activity in October and November alone. The rise in tensions and violence and restrictions on access are the main drivers of this decline, which is manifested in a sharp drop in sales, primarily to customers from Israel (85 per cent decline) and the rest of the West Bank (70 per cent decline); reduced access to agricultural lands and quarries; over 90 per cent decline in the access of workers without permits to the Israeli labor market (around 20,000 before October), and 35 per cent decline for those with permits (around 22,000); and reluctance by wholesalers and importers to accept deferred payments.

“Despite the occupation and the closures, I still love life”, says Khadra, a 60 year-old woman from al Fawwar camp (Hebron)

Al Fawwar refugee camp, to the south of Hebron and home to over 8,300 people, was severely hit by access restrictions following the installation of a gate closing the main route leading to Hebron city. This junction was the scene of a number of stabbing and ramming attacks or alleged attacks.

Al Fawwar refugee camp, to the south of Hebron and home to over 8,300 people, was severely hit by access restrictions following the installation of a gate closing the main route leading to Hebron city. This junction was the scene of a number of stabbing and ramming attacks or alleged attacks.

Khadra, a mother of seven from al Fawwar, suffers from kidney failure which impairs her mobility. The closure restricted her ability to attend Hebron hospital, where she receives dialysis three times a week. She now has to travel via Yatta, which takes about one hour longer than the regular route, in a special taxi that costs about NIS 240 ($60) per day. The precarious state of the alternative route is a concern: “on one of the trips back from a dialysis session, I began bleeding due to bumps in the road and had to be treated at the camp clinic,” Khadra recalls. However, she pointed out that “despite the occupation and the closures, I still love life.”

The gate on the main entrance to al Fawwar camp has now been opened and movement to and from Hebron city has returned to normal.