Olive harvest 2023: hindered access afflicts Palestinian farmers in the West Bank

The 2023 olive harvest season was particularly difficult for Palestinian farmers in the West Bank. Taking place around September-November, it coincided with the 7 October attack on Israel and the escalation of hostilities in the Gaza Strip. During that time, Palestinians across the West Bank faced a spike in movement restrictions and violence by Israeli forces and Israeli settlers.

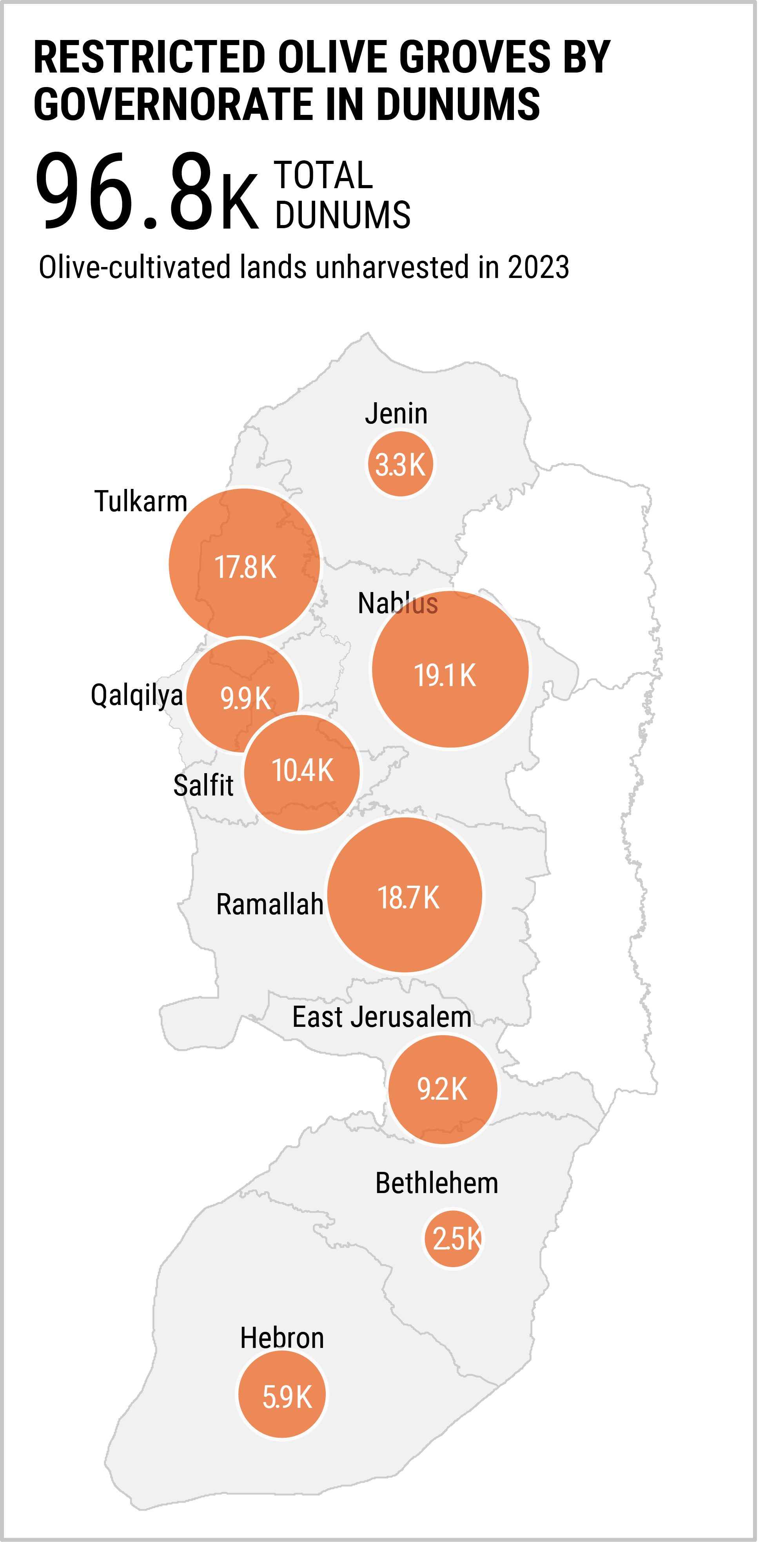

For Palestinian olive harvesters, this resulted in immense hardships as they often could not access their olives. More than 96.000 dunums of olive-cultivated lands across the West Bank remained unharvested following the 2023 season, due to Israeli restrictions on Palestinian access. They include cultivated olives in four types of locations:

- Behind the West Bank Barrier, in the so-called “Seam Zone”

- Bordering the Barrier, within 150 metres on the “West Bank” side

- Near settlements, where scheduled military permissions (referred to as “prior coordination”) have traditionally been required

- In other areas adjacent to settlements

In previous years, the Israeli authorities would require a so called “prior coordination,” in fact a scheduled Israeli military permission, farmers to access their lands in certain areas. However, in the 2023 season, the Israeli authorities cancelled almost all of these approvals, effectively preventing farmers from accessing their lands. Agricultural gates along the West Bank Barrier remained overwhelmingly closed.

According to the Food Security Sector, a partnership of dozens of humanitarian organizations, Palestinian farmers suffered an estimated total loss of more than 1,200 metric tons of olive oil in the 2023 season, resulting in a direct financial setback of US$10 million. The impact was particularly harsh in the northern governorates of Tulkarm, Qalqiliya and Nablus.

The olive harvest is a key economic, social and cultural event for Palestinians. As the Occupying Power, Israel should ensure that Palestinians are able to participate in, and fully benefit from, this activity. This includes ensuring that farmers can access their olive trees throughout the year, and that their trees and agricultural property are protected from damage and theft.

The olive harvest is a key economic, social and cultural event for Palestinians. As the Occupying Power, Israel should ensure that Palestinians are able to participate in, and fully benefit from, this activity. This includes ensuring that farmers can access their olive trees throughout the year, and that their trees and agricultural property are protected from damage and theft.

Additionally, during September-November, OCHA documented 113 harvest-related cases where Israeli settlers attacked Palestinians, damaged their trees or stole crops and harvesting tools. Of these, ten incidents resulted in casualties and property damage, another ten resulted in casualties but not property damage, and 93 incidents resulted in damage but not casualties. Over 2,000 trees were vandalized during these incidents. The highest numbers of incidents were recorded in the governorates of Nablus (40) and Ramallah (31). OCHA estimates that, overall in 2023, over 10,000 Palestinian-owned olive trees were vandalized presumably by settlers across the West Bank.

On 28 October, a 29-year-old Palestinian, a father of four children, was shot and killed by an Israeli settler while harvesting olive in As Sawiya village, south of Nablus. Bullet holes were observed in his chest and left forearm.

On at least 38 occasions, Palestinian farmers or other eyewitnesses reported that Israeli forces had accompanied the attackers or that the latter had been wearing military uniforms while expelling Palestinians from farmlands or taking over olives and tools.

Map by OCHA and the Palestine Food Security Sector. For a PDF version click here.

Hindered access to trees isolated by the West Bank Barrier

Palestinians in about 150 Palestinian communities across the West Bank have olive farmlands in the area between the Green Line and the West Bank Barrier. Through litigation, farmers have long ago managed to increase the number of gates erected by the Israeli authorities along the Barrier. While 69 such gates have been designated for farming purposes, year-round access is not allowed through most of them. Instead, most agricultural gates would only open during the olive harvest season, for limited time every day. That said, in the aftermath of 7 October, the Israeli authorities decided to keep all of them closed. Gates only opened for the 2023 harvest on an exceptional basis, between 24 and 30 November, while a humanitarian pause was implemented in Gaza and Israel.

Additionally, Palestinian farmers report that Israeli forces prevented them from accessing olive-cultivated lands that are not isolated by the Barrier but are within about 150 meters of it, on the “West Bank” side.

OCHA’s monitoring in the northern West Bank shows that the 2023 olive yield in the area isolated by the Barrier was 93 per cent lower compared with the yield in accessible areas. On average, reduction was of 74 per cent between 2011 and 2022, and 60 per cent between 2010 and 2022.

Impact on Olive productivity in Akkaba (Tulkarm)

In the 2023 season, due to the Israeli authorities’ closure of all agricultural gates along the Barrier, some eighty families in Akkaba village, in the northern governorate of Tulkarm, were unable to harvest their olives. Some 80 per cent of this village’s lands, or 2,500 dunums, are behind the West Bank Barrier, and most of them are planted with olives.

In the 2023 season, due to the Israeli authorities’ closure of all agricultural gates along the Barrier, some eighty families in Akkaba village, in the northern governorate of Tulkarm, were unable to harvest their olives. Some 80 per cent of this village’s lands, or 2,500 dunums, are behind the West Bank Barrier, and most of them are planted with olives.

Taysir Amarneh, is a farmer from this community, with olive trees on either side of the Barrier. As the agricultural gate allocated for the village only opened on 28-30 November, and even then, no more than twice per day, Amarneh only managed to harvest some 10 per cent of his crops. This resulted in a 78 per cent reduction in yield, compared with that of his trees on the accessible side of the Barrier.

“Alongside this season’s reduction in yield, the repercussions will continue into the next season if the gates stay closed and we lose the plowing and pruning schedule,” Amarneh said. He also explained that considering the reduction in his olive yield, the continuous closure of the Barrier gates, and the limitation on humanitarian space and funds, he watched helplessly as his land and trees remain with no plowing or pruning services.

Hindered access to land taken over by Israeli settlements

The access of Palestinians to olive-cultivated lands is also restricted by the presence of Israeli settlements and practices associated with them.

Palestinians in at least 110 communities across the West Bank own land within or near 56 Israeli settlements. Much of this land has long ago been declared by the Israeli authorities a “closed military zone” and may only be accessed by Palestinian farmers through special authorization by the Israeli authorities, which could be granted for limited days during the harvest and plowing seasons.

Almost half of the lands that required scheduled military permissions are in Nablus governorate, followed by Salfit and Qalqiliya, while the remainder are distributed between Ramallah, Hebron, and Bethlehem governorates. However, in the 2023 season, the Israeli authorities did not authorize such access in most locations that typically required scheduled authorization.

In addition, Palestinian farmers were denied access to their olive trees in Area C of the West Bank where these lands had previously been accessible without any kind of restrictions. These new restrictions were marked by earth mounds, closed road gates, and cement blocks. Furthermore, denial of access was also reported in Area B of the West Bank; for instance, farmers were denied access to about 700 dunums in Qaryut village (Nablus), and 1,900 dunums in Turmus’ayya (Ramallah).

Impact on productivity in Turmus’ayya (Ramallah)

According to people in the village of Turmus’ayya, over 180 Palestinian farmers had said they could not access their land that are located near the Israeli settlement of Shilo or its “outposts” (unofficial settlement areas) during the 2023 season. Consequently, about 2,500 dunums, including 1,000 dunums in areas typically requiring scheduled military approvals to access and 1,500 dunums in other parts of Area C or Area B, remained unharvested.

According to people in the village of Turmus’ayya, over 180 Palestinian farmers had said they could not access their land that are located near the Israeli settlement of Shilo or its “outposts” (unofficial settlement areas) during the 2023 season. Consequently, about 2,500 dunums, including 1,000 dunums in areas typically requiring scheduled military approvals to access and 1,500 dunums in other parts of Area C or Area B, remained unharvested.

The Abu Awwad family from Turmusa’yya is profoundly affected by the Israeli settlement of Shilo and its “outposts,” built in close proximity to where they live. The family has olive trees in Area C that require scheduled military approvals. During the 2023 season, family members managed to harvest olives only on Fridays for three weeks without scheduled military approvals. However, while harvesting, they were attacked by armed Israeli settlers protected by Israeli forces. Abdullah, a family member, was physically assaulted, and the olives he collected, along with harvesting equipment, were damaged.

Additionally, after 7 October, Israeli forces positioned themselves between the settlement and the family’s house, blocking the main entrance with an earth mound that restricted the family's movement.

"Not only did we experience 70 per cent loss in this season's production, but we also witnessed our olive fruits in the adjacent inaccessible groves falling to the ground, as we were unable to harvest them. On top of that, we grapple daily with challenges to meet our basic needs, all while having to ‘coordinate’ every movement with the Israeli forces stationed near my house," said Abdullah.