Over 700 road obstacles control Palestinian movement within the West Bank

In July 2018, OCHA completed a comprehensive ‘closure survey’ that recorded 705 permanent obstacles across the West Bank restricting or controlling Palestinian vehicular, and in some cases pedestrian, movement. This figure is three per cent higher than in December 2016, the date of the previous survey. These obstacles are deployed by Israeli forces citing security concerns. The deployment of obstacles has become more flexible and, combined with the relatively low level of violence since the completion of the previous survey, has a less disruptive impact on the daily life of Palestinians travelling between Palestinian localities (excluding East Jerusalem and the H2 area of Hebron city) than previously.

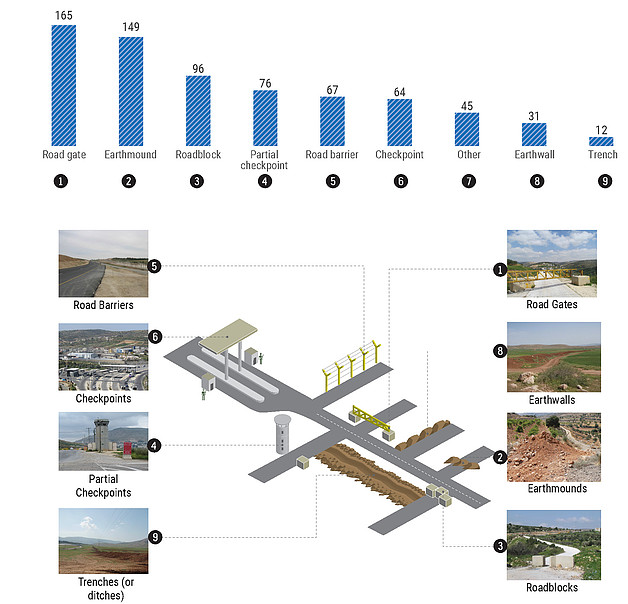

West Bank obstacle types

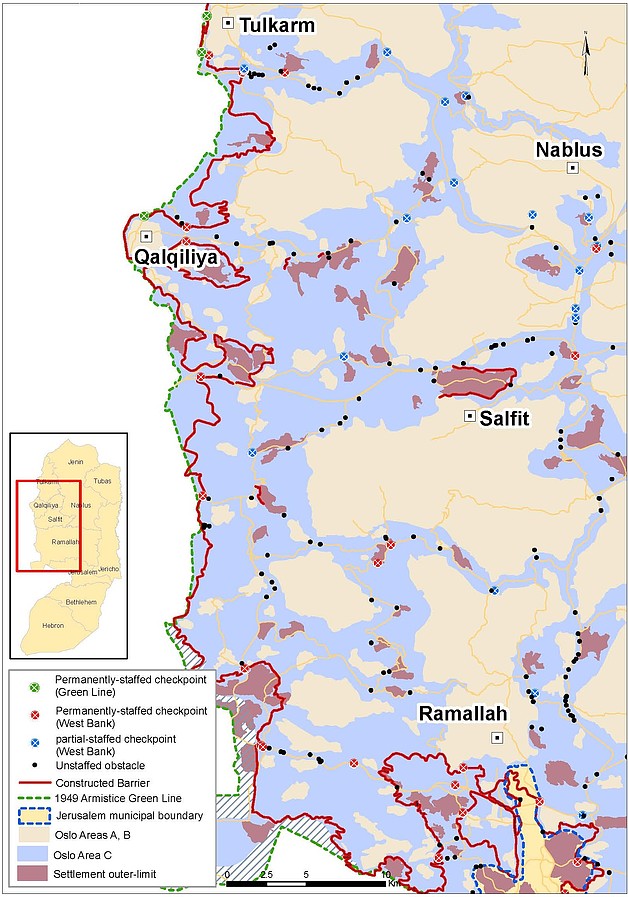

Obstacles include 140 fully or occasionally-staffed checkpoints, 165 unstaffed road gates (of which nearly half are normally closed), 149 earth mounds and 251 other unstaffed obstacles (roadblocks, trenches, earth walls, etc). The most significant difference observed since the last survey in terms of the category of obstacle are the addition of 36 road gates and the removal of 31 earth mounds. The largest net increase was recorded in Ramallah governorate with a total of 15 additional obstacles.

West Bank obstacles: central and northern areas

All the 140 checkpoints include permanent infrastructure but only 64 of them are permanently staffed with security forces, including 32 located along the Barrier or on roads leading to Israel, 20 in the Israeli-controlled area of Hebron city (H2), and the other 12 elsewhere in the West Bank. The other 76 (partial) checkpoints are either occasionally staffed or have security personnel located in a tower rather than on the ground. Excluded from these figures are eight checkpoints located on the Green (1949 Armistice) Line.

Between January 2017 and the end of July 2018, Israeli forces employed an additional 4,924 ad-hoc “flying” checkpoints, or nearly 60 a week. These involve the deployment of Israeli forces for several hours on a given road for the purpose of stopping and checking Palestinian drivers and vehicles, but without any permanent physical infrastructure on the ground.

An adaptable system of control

In recent years, the system of road obstacles has increasingly allowed Israeli forces to quickly close or open any given area depending on the level of tension. The majority of obstacles (some 80 per cent) are not staffed and are used to funnel Palestinian traffic towards a restricted number of junctions controlled by checkpoints. During times of calm, these checkpoints are mostly unstaffed or security personnel carry out occasional checks on vehicles. By contrast, when tensions arise, checkpoints are mostly staffed and vehicles are stopped more frequently, generating delays. This occurred on a wide scale during the last quarter of 2015 following an escalation in Palestinian attacks and mass demonstrations, and had a significant humanitarian and economic impact, particularly across Hebron governorate.[1]

At checkpoints located along the Barrier or on roads leading to occupied East Jerusalem or Israel, strict checks are carried out at all times and only Palestinian pedestrians holding special permits are allowed to pass. These checkpoints prohibit the vast majority of the Palestinian population from accessing areas behind the Barrier (the “Seam Zone”) and East Jerusalem, while controlling access by those holding special permits to these areas or to workplaces in Israel.

Expansion of the more flexible system can be seen in the higher number of road gates, which can be opened and closed depending on the circumstances, versus a decline in fixed earth mounds. Given the relatively calm conditions prevailing during the reporting period, more than half of road gates were classified as “mostly open”. This trend is also consistent with the frequent deployment of flying checkpoints, which are the most mobile type of obstacle.

Closure of entrances to villages

In recent years, the Israeli military has blocked vehicle access to the main entrances of Palestinian localities from which stones have been thrown at Israeli vehicles or where the homes are located of the perpetrators or suspected perpetrators of attacks against Israelis. Since January 2017, OCHA has documented 93 such incidents affecting a total of 30 communities.[2]

In a 2017 report to the Human Rights Council, the UN Secretary General stated that measures such as the closure of Palestinian towns and villages following attacks against Israelis “may amount to collective punishment”.[3]

In most cases, Israeli military officers communicate to the Palestinian District Coordination Offices or heads of village councils that the closures are connected to incidents like those described above. In most cases, the closure does not directly prevent Palestinian youths from reaching main roads on foot to throw stones at Israeli vehicles. Similarly, closures following stabbing or shooting attacks are implemented in the home town of perpetrators, irrespective of the actual location where the attack took place.

The closures vary in their severity (from total closure to strict checks on vehicles) and may last for a few days to a number of weeks. Residents are forced to cross a roadblock or checkpoint on foot to reach public transportation on the other side, or to resort to longer detours. This disrupts access to services and livelihoods, with a disproportionate impact on children, the elderly and disabled people.

Impact on humanitarian agencies

Checkpoints deployed across the West Bank, particularly those controlling access into East Jerusalem, Israel and the “Seam Zone”, also have a disruptive impact on the operations of humanitarian organizations. Staff at eleven checkpoints operated by private security companies systematically demand to search INGO vehicles, including those of UN agencies in violation of the UN’s privileges and immunity. As a result, UN staff are forced to avoid these checkpoints and take long detours. Access by national staff through another five checkpoints staffed by Israeli forces requires both ‘prior-coordination’ and a special permit.

During 2017, 341 access restriction incidents at West Bank checkpoints were reported by UN and INGOs, a significant increase from the previous year (131 cases). The number of working hours lost in relation to these incidents soared from 1,262 in 2016 to 10,473 in 2017. The majority of incidents involved demands to search UN buses and for staff to exit the buses during these searches. The largest number of incidents in 2017, 37 per cent, was recorded at al Walaja checkpoint, located on the Green Line, which controls access between the southern West Bank and Jerusalem. The number of such incidents has declined since the start of 2018 following instructions by the Israeli authorities to allow UN staff to remain on buses, and to conduct vehicle searches only if checkpoint personnel have a specific suspicion.

A broader system of access restrictions

Road obstacles are an integral component of a broader system of access restrictions, citing security reasons, that impedes the movement of Palestinians within the West Bank and contributes to geographical fragmentation. This system includes the Barrier, 85 per cent of which lies inside the West Bank. Palestinians must obtain special permits or engage in ‘prior coordination’ to reach their land or homes between the Barrier and the Green Line. The permit requirement applies to West Bank ID holders for entry into East Jerusalem (except for men aged over 55 and women over 50). There are prohibitions or restrictions on the use of 400 kilometres of roads serving Israeli settlers almost exclusively; access is closed to some 20 per cent of West Bank land on the grounds that these areas are designated as ‘firing zones’ for military training or a border buffer zone’; and the prohibition extends to over 10 per cent of West Bank land located within the municipal boundaries of Israeli settlements.

Under international law, Israel has an obligation to facilitate the free movement of Palestinians across the occupied Palestinian territory, including East Jerusalem. Exceptions to this obligation are recognized only for imperative reasons of security and only in response to specific security threats. In its 2004 Advisory Opinion, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) established that the sections of the Barrier which run inside the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, together with the associated gate and permit regime, violate Israel’s obligations under international law.

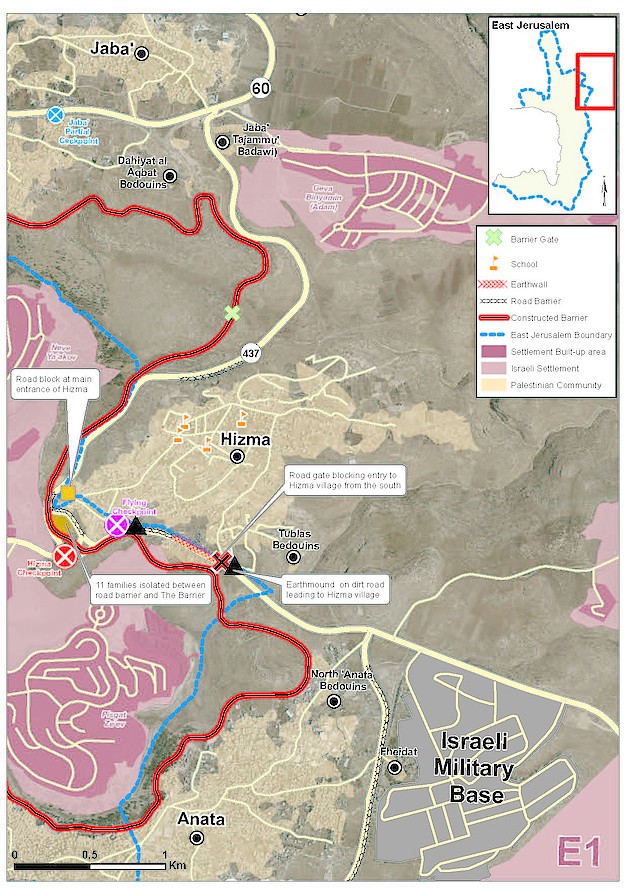

The case of Hizma village

Hizma is a Palestinian village of over 7,000 residents in Jerusalem governorate. The bulk of its built-up area is in Area B but small parts of the village lie in Area C or within the municipal boundaries of Jerusalem, although it is separated from the rest of the city by the Barrier. Between 28 January and the end of March 2018, the three access roads into the village were either totally or partially closed to Palestinian traffic. The Israeli army hung posters on village shops stating that the army “will continue its work so long as you [residents] continue to be disruptive”. Other posters showed broken windshields. Following communications with the Israeli military, the head of the village council reported that the posters justified the closures as a response to stone throwing by Palestinian youths at vehicles with Israeli number plates. In 2017 and the first two months of 2018, OCHA recorded 11 incidents of Palestinians throwing stones at Israeli vehicles near Hizma that resulted in Israeli injuries or damage to vehicles.

The closures disrupted access by Hizma’s residents to services and livelihoods. Traffic between the north and south of the West Bank that passed through the village was diverted, undermining the commercial life of the village. Service providers, including a third of the teachers in village schools who commute on a daily basis, faced delays reaching the village. Over 50 shops/businesses that are the main source of income for 150 households were affected by the diversion of Palestinian traffic away from the village. Family life was also affected by the unpredictable nature of the closures.

[1] See, OCHA, Humanitarian Bulletin, January 2016. Available at: https://www.ochaopt.org/content/movement-restrictions-west-bank-roads-t…

[2] The affected communities are: Ya’abad (Jenin); Osarin, Madama, al Lubban ash Sharqiya, Huwwara, Tell and Beita (Nablus); Azzun and Izbat at Tabib (Qalqiliya); Kafr ad Dik (Salfit); Husan, Beit Ta’mir and Jannatah (Bethlehem); Al Fawwar Camp and Marah Rabah (Hebron); Hizma, the Old City, Biddu, Beit Iksa, and Beit Surik (Jerusalem); Deir Abu Mash’al, Ein Yabrud, Kobar, Beitillu, al Jalazun camp, al Bireh, Deir Nidham, al Mughayyir and Sinjil (Ramallah).

[3] Report by the Secretary General, Human rights situation in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including East Jerusalem, A/HRC/34/38, April 2017, para. 32-33,