Plan progresses to transfer Bedouin communities in central West Bank

Ongoing demolitions in at-risk communities act as a “push factor”

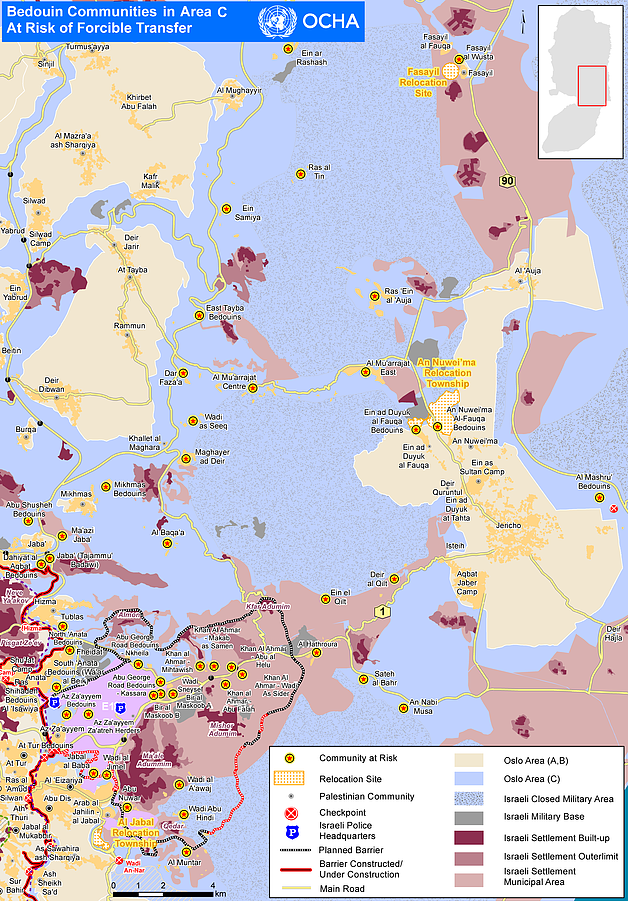

In December, another step was taken in the Israeli plan to “relocate” around 7,000 Palestinian Bedouin currently residing in 46 small residential areas in Area C in the central West Bank.[1] The time period allocated by the Israeli Civil Administration (ICA) for the filing of objections to outline plans for the establishment of a Bedouin town in An Nuwei’ma, next to Jericho city, the largest of the three relocation sites identified by the Israeli authorities, has now expired.

In a briefing provided to a Knesset sub-committee in April 2014, a senior Israeli Minister of Defense officer reportedly justified the relocation plan on the grounds that the residents lack title over the land on which they currently reside and that their relocation will improve their living conditions and access to services. The residents, the majority of whom are registered refugees, oppose the proposed relocation and insist on their right to remain at their current site or to return to their original homes and land in southern Israel, from which they were evicted in the early 1950s.

Following the deposition of the plans for An Nuwei’ma town for public review in August 2014, dozens of objections were submitted. Arguments highlighted the unsuitability of the proposed site to the pastoral lifestyle of these communities; the negative socio-economic impact of the relocation; the feasibility of services provision in their current locations; and the failure of the plan to conform to provisions in international humanitarian law (IHL). The UN Secretary-General has stated that the implementation of the proposed plan could amount to individual and mass forcible transfers and forced evictions, prohibited under IHL and human rights law.[2]

The ICA is currently reviewing the objections submitted; the timeframe for this is not specified. Once complete, the ICA should publish the reviewed plans again for a period of 45 days, during which petitions against them could be filed with the Israeli High Court of Justice (HCJ). After this period, the outline plans will enter into force, unless the HCJ orders otherwise.

Although the formal window of opportunity to appeal the outline plans before the Israeli HCJ has not begun, some of the affected communities filed two related petitions this month. One of them requested the court to oblige the ICA to disclose all relevant details of the relocation plan, including the names of communities and their planned destinations. The other petition requested an interim injunction freezing the planning process on the grounds of inadequate consultation with the affected communities.[3]

Israeli demolitions and confiscations continue

The advancement of the “relocation” plan is taking place alongside various Israeli practices that create a coercive environment and which function as a “push factor”. These practices include demolition orders against the majority of the existing structures in the affected communities on the grounds that they lack building permits, plus the demolition or seizure of donor-funded assistance, provided by the international community to support the residents in their current locations.

Although the ICA has committed not to implement orders that are the subject of a petition at the HCJ until a relocation site is made available to the people living in these structures, the demolition and requisition of structures against which no petitions have been filed has continued. In 2014, the ICA demolished, dismantled and seized approximately 70 residential and livelihood-related structures in at least ten of the communities at risk of forcible transfer.[4] Over a third of these structures were funded by international donors and provided as humanitarian assistance.

The majority of demolitions and seizures took place in communities located in the Jerusalem periphery. Much of this area has been allocated for the expansion of Israeli settlements, including the construction of thousands of settlement housing and commercial units between the Ma’ale Adumim settlement and Jerusalem as part of the E1 plan. This plan has been opposed consistently by the international community in the belief that it will undermine a two-state solution. Large areas of land are also at risk of being surrounded by the Barrier.

Responding to the needs of communities at risk of forcible transfer

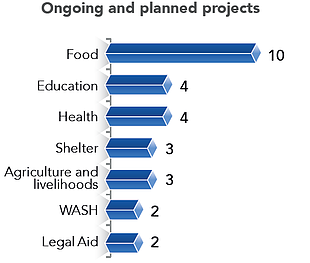

With the aim of identifying gaps and improving the quality of their response, humanitarian organizations conducted a joint mapping of interventions targeting the Bedouin communities at risk of forcible transfer. Initial findings indicated that at present there are a total of 28 projects under implementation or planned for 2015. These projects involve the delivery of material assistance, including food, emergency shelters, winterization kits, latrines and water tanks, and essential services, such as primary health care, psychosocial support, veterinary services, awareness raising on nutrition and hygiene issues, and legal support to prevent demolitions and displacement.

With the aim of identifying gaps and improving the quality of their response, humanitarian organizations conducted a joint mapping of interventions targeting the Bedouin communities at risk of forcible transfer. Initial findings indicated that at present there are a total of 28 projects under implementation or planned for 2015. These projects involve the delivery of material assistance, including food, emergency shelters, winterization kits, latrines and water tanks, and essential services, such as primary health care, psychosocial support, veterinary services, awareness raising on nutrition and hygiene issues, and legal support to prevent demolitions and displacement.

[1] OCHA Factsheet: Bedouin Communities at Risk of Forcible Transfer, September 2014.

[2] Report by the UN Secretary General to the UN General Assembly, A/69/348, pp. 6 and 7. See also A/67/372, 14 September 2012, para. 37.

[3] The petitioners were supported by members of the Protection Cluster. For further details, see Amira Hass, West Bank Bedouin fighting Israel’s plan for forcible relocation, Haaretz, 3 Dec 2014.

[4] OCHA Protection of Civilians Database.