Reconstruction of 15 per cent of homes destroyed or severely damaged during the 2014 hostilities

Funding still urgently needed for reconstruction and shelter assistance to over 90,000 people still displaced

At the end of 2015, more than 16,000 families (over 90,000 individuals) remained displaced as a result of the 2014 Gaza-Israel hostilities, which destroyed 11,000 homes and severely damaged or rendered uninhabitable an additional 6,800 homes. The living conditions of these families raise a range of protection concerns, including overcrowding, limited access to basic services, lack of privacy, tensions with host communities, risks due to unexploded ordnance and exposure to adverse weather.

Durable solutions

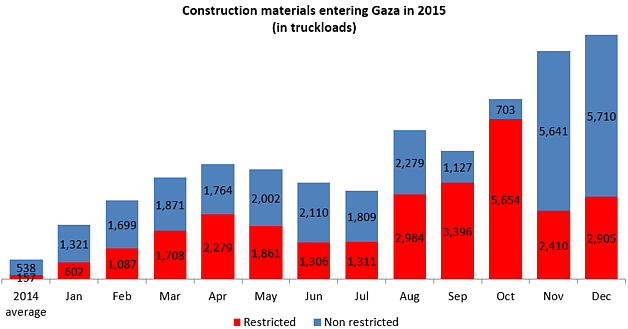

Progress in rebuilding and repairing these homes was initially slow in 2015. However, following an agreement between Israel and the State of Palestine in June 2015 on the import of restricted building materials (the “residential stream”), the volume of reconstruction gradually increased over the second half of 2015. This is clearly evidenced in the 78 per cent increase in the quantity of building materials entering Gaza during that period compared with the first half of the year, and the largest monthly average of such materials since the imposition of the blockade in June 2007. This trend was facilitated by the Israeli authorities’ expansion of the Kerem Shalom crossing and the removal of the restrictions on the import of aggregates.

By the end of January 2016, around 15 per cent of displaced families (2,703) were able to return to homes that had been repaired or reconstructed. The repair and reconstruction of an additional 2,000 homes, or 11 per cent of the caseload, is ongoing, with many of these homes nearing completion.

These homes were reconstructed or repaired by their owners after receiving cash assistance from UN agencies or other international support. Grants offer up to $50,000 per unit for reconstruction and an average of $12,000 for repairs. Some families have also started to carry out repairs using their own resources or by accessing loans or credit.

Despite this progress, one year and a half after the end of the hostilities, the reconstruction or repair of the homes of 74 per cent of displaced families is yet to start. Funding has been confirmed for some 4,200 families (24 per cent of the caseload) to repair or reconstruct their homes in 2016, leaving a funding gap for 8,900 families (or about half of the caseload) who have no end in sight to their displacement.

Temporary shelter assistance

Displaced families are assisted with various forms of temporary shelter pending a durable solution. In the initial period of displacement, during the war and its aftermath, thousands of families were sheltered in collective centres managed by UNRWA; the last such center closed in June 2015. Other forms of assistance have included: cash for rent, cash to finish buildings under construction, prefabricated caravans and longer term (2-5 years) temporary shelters.

Since the end of the hostilities and up to the end of 2015, over 17,000 displaced families had received cash assistance for rent payments of $200-$250 per household. However, as of January 2016, only $2.5 million of the $9.5 million required for 3,150 non-refugee families in 2016 had been secured, leaving a gap of $7 million (or 2,050 families). Meanwhile, UNWRA requires $24.3 million to support its refugee caseload in 2016 (9,000 families).

In addition, 68 families received assistance to complete the construction of unfinished buildings; 720 displaced families received prefabricated caravans; and another 433 received transitional wooden shelters. Most displaced families also received some type of emergency assistance which includes non-food items such as bedding, mattresses, kitchen and hygiene kits; winterization assistance or sealing-off kits such as tarpaulins, plastic sheeting and cash or construction materials; and a one-time cash reintegration grant provided to 22,176 displaced families for a total of $15.35 million.

The IDP Re-Registration and Vulnerability Profiling Exercise

At the height of the hostilities in July-August 2014, there were nearly 500,000 internally displaced persons (IDPs), constituting 28 per cent of the population. During the hostilities, UNRWA and the Ministry of Social Affairs in Gaza conducted an initial registration of IDPs, but these records became outdated following the ceasefire in August 2014, when the majority of IDPs abandoned shelters and host homes without an organized deregistration being conducted. Since then, the ability of humanitarian actors to respond to the needs of IDPs has been hampered by significant gaps in registration and profiling, which are critical to establishing the location of the IDPs and their living conditions, vulnerabilities and specific needs. To cover these gaps, the IDP Re-Registration and Vulnerability Profiling exercise, an inter-sectoral humanitarian initiative coordinated by OCHA, was conducted between August and December 2015, involving field visits to approximately 18,000 displaced families to document their living conditions. The main findings are expected to be released in March 2016.

At the height of the hostilities in July-August 2014, there were nearly 500,000 internally displaced persons (IDPs), constituting 28 per cent of the population. During the hostilities, UNRWA and the Ministry of Social Affairs in Gaza conducted an initial registration of IDPs, but these records became outdated following the ceasefire in August 2014, when the majority of IDPs abandoned shelters and host homes without an organized deregistration being conducted. Since then, the ability of humanitarian actors to respond to the needs of IDPs has been hampered by significant gaps in registration and profiling, which are critical to establishing the location of the IDPs and their living conditions, vulnerabilities and specific needs. To cover these gaps, the IDP Re-Registration and Vulnerability Profiling exercise, an inter-sectoral humanitarian initiative coordinated by OCHA, was conducted between August and December 2015, involving field visits to approximately 18,000 displaced families to document their living conditions. The main findings are expected to be released in March 2016.

“I’m tired and can’t continue living in these conditions” – Hind Hassna, internally displaced woman, Gaza city

Prior to the 2014 hostilities, Hind Hassna, 36, her three boys and two girls, her parents and sister lived with her brother’s family of eight in a small house in eastern Gaza city. Hind’s husband left the family 11 years ago and since then, she has been raising her children alone, as well as taking care of her disabled father.

In July 2014, the family house was completely destroyed by an Israeli airstrike in eastern Gaza city and the whole family was forced to move to an UNRWA shelter. Following the ceasefire, the family moved into a rented apartment, but were forced to vacate it shortly after due to their inability to pay rent.

“We had no choice but to move to my nephew’s house in Ash Shuja’iyeh neighbourhood, which consists of three rooms made of asbestos: my nephew and his wife live in one room, my brother’s family in another room, and the nine of us in the third one. We are 17 people relying on the same bathroom, which has no shower. Some of the windows are broken and are simply covered with plastic. These days it’s very cold.

I receive 930 shekels [approximately $235] every three months from the Ministry of Social Affairs, but this can barely cover our basic needs. I want to send my youngest son and daughter to some recreational activities at the family centre, but I cannot afford the transportation costs. I feel totally depressed. I’m tired and can’t continue living in these conditions.”

* This article is based on a contribution by the Shelter Cluster