West Bank demolitions and displacement continue at similar pace to 2017

Concern over 44 schools in Area C and East Jerusalem threatened with demolition

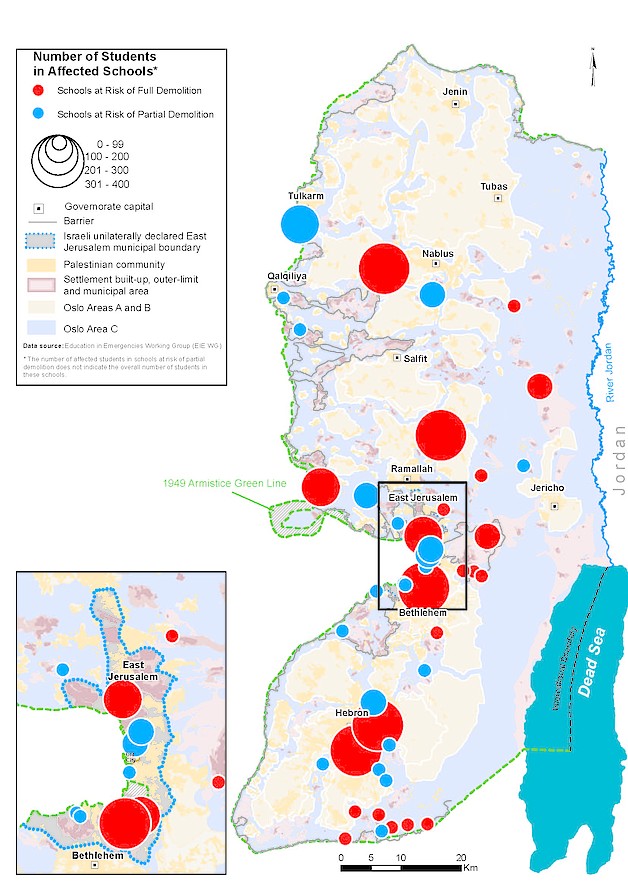

During the first two months of 2018, the Israeli authorities demolished or seized a total of 70 Palestinian-owned structures across the West Bank. On average, this is the same number of monthly demolitions recorded in 2017 (35), and around one-third of figures recorded in 2016 (91). Around 30 per cent of the structures targeted in 2018 were residential and 81 people were displaced. The remainder were livelihood-related or public structures, including two school classrooms. An assessment by humanitarian actors of the education sector indicates that 44 Palestinian schools in the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, are at risk of full or partial demolition or seizure due to the lack of an Israeli-issued building permit.

Monthly average of demolitions and displacement across the West Bank

East Jerusalem

Over half of the demolitions recorded during the reporting period (36 of 70) took place in East Jerusalem and were on the grounds of the lack of a building permit, which is very difficult to obtain. Unlike the general trend recorded for the West Bank, the monthly average for this period in East Jerusalem (18 structures) was higher than figures for both 2017 and 2016 (12 and 16 structures respectively), during which OCHA recorded the highest rates of demolition in East Jerusalem since 2000.

In one incident in Al ‘Isawiya (30 January), the Israeli authorities demolished twelve commercial and animal structures that were the source of livelihood for nine families. Al ‘Isawiya remains one of the East Jerusalem communities most affected by demolitions, followed by Beit Hanina and Jabal Al Mukkabir, both of which recorded the highest levels of demolitions in 2017.

In Bir Onah, a residential area in the southern part of the Jerusalem municipal area, physically severed from the city by the Barrier, the Israeli authorities demolished two multi-storey buildings under construction on 29 January. This is the first demolition recorded by OCHA in this area since 2009. In recent years, municipal areas behind the Barrier have seen ‘wildcat’ construction driven by the broader planning crisis in East Jerusalem and lack of an appropriate planning and zoning regime. The buildings targeted in Bir Onah were located next to the ‘tunnels road’ that connects the Etzion settlement bloc to Jerusalem; there are plans for this road to be upgraded and widened.

Area C

Over 40 per cent of the structures targeted in January and February (29 of 70) were in communities partially or entirely located in Area C; this is a major decline compared with the monthly average in 2017 (14 vs. 23).

Fourteen (14) of the demolished structures were funded by donors and had been provided as humanitarian assistance to five vulnerable Bedouin communities. In the Qurzaliya area of al Jiftlik in the central Jordan Valley, the Israeli authorities demolished two residential and four animal shelters worth about €7,700 that had been provided in response to an earlier demolition one year ago. A family residing in this community, designated by the Israeli authorities as a ‘firing zone’, was affected and the road leading to this area was damaged and blocked following the demolitions.

On 4 February, in the Palestinian Bedouin community of Abu Nuwar in Jerusalem governorate, the Israeli authorities demolished two newly built classrooms funded by donors and which served 26 third and fourth grade students. This is the sixth demolition or confiscation incident in Abu Nuwar school by the Israeli authorities since February 2016. The community is located in an area allocated and planned by the Israeli authorities for the expansion of Ma’ale Adumim settlement (the E1 plan). It is one of the 46 communities in the central West Bank at risk of forcible transfer due to the coercive environment exerted upon them, including the promotion of relocation plans.

The acting Humanitarian Coordinator for the OPT, Roberto Valent, raised concerns over the targeting of the school and called on the Israeli authorities “to fulfill their obligations under international humanitarian and human rights law and immediately cease all practices that are directly or indirectly generating a risk of forcible transfer for Palestinians in various parts of the West Bank, including the destruction of schools and related property”.

Area A

Another five structures demolished during the reporting period, including three homes and two livelihood structures, were located in Area A of the Jenin governorate; their demolition resulted in the displacement of 31 people, including eight children. The structures were destroyed, citing military needs, during two search and arrest operations to capture the suspected perpetrators of a shooting attack on 9 January 2018, in which an Israeli settler was killed. During one of the operations, four residential apartments sustained damage, temporarily displacing 15 people (not included in the totals). Clashes that erupted during the operations resulted in the killing of two Palestinian men, including one of the wanted persons, and the injury of another 33 people.

Schools at risk of demolition

Based on a series of field visits and interviews, partners working in the education sector (the Education in Emergency Working Group) identified 36 schools in Area C and eight in East Jerusalem that are at risk of full or partial demolition due to outstanding orders affecting all or part of their facilities. These schools currently serve about 5,000 children.

Some children living in Area C have no access to a primary school in their communities and must walk or travel long distances to reach a school. They are often exposed to settler harassment or searches at checkpoints. These constraints undermine the quality of education and increase the chances of early dropout.

A needs assessment carried out by OCHA in 2017 found that only six of the 46 Bedouin communities in the central West Bank at risk of forcible transfer have a primary school within the community, and all of the schools are at risk of demolition. The Palestinian Ministry of Education provides transportation to schools for children residing in 20 of the remaining communities, while children in the other 20 communities must walk or travel up to six kilometres to reach their schools.

In East Jerusalem, a chronic shortage of classrooms and substandard or unsuitable conditions of existing facilities has long been recognized as ‘the most pressing of the many serious problems in education in East Jerusalem’. According to the Association of Civil Rights in Israel, in addition to the shortage of around 2,000 classrooms in the municipal system, almost half of the 1,815 classrooms in the municipal system were considered sub-standard.

The case of Wadi as Seeq school

Wadi as Seeq is a Palestinian Bedouin community in northeastern Ramallah governorate, one of 46 communities in this area at risk of forcible transfer. It is home to some 150 people, 62 per cent of whom are children. Residents rely on grazing as their primary source of income. As the community is not connected to the water network, they rely on water tankers and report paying more than NIS20 per cubic meter, over four times the price of piped water.

On 30 September 2017, a primary school was established in the community with support from an international NGO and opened to serve 82 students from 1st through 6th grade from Wadi as Seeq and three nearby communities. It comprises three zinc structures cemented to the ground with tiling inside and includes six classrooms, a kitchen, a staffroom and the principal’s room. Community sources reported that up 20 of the children enrolled this year were over the age of seven and had never attended school previously due to the travel distances and transportation constraints.

A community representative approached by OCHA commented: “Our life changed dramatically following the establishment of the school...Children now love to go to school. They are very happy and their school performance has already improved. We are also relieved that they are nearby and safe, and this is enough for us.”

On 2 October, officials from the Israeli Civil Administration (ICA) arrived at the community, took photographs of the school, and informed the residents that the structures would be seized as they are considered as mobile and were installed without a permit. To prevent the seizure, the community requested that the ICA waive the need for a permit as per a provision in military legislation. This was rejected and the community filed a petition against the rejection to the Israeli Supreme Court; a ruling is pending.