Movement and Access in the West Bank | August 2023

Key Facts

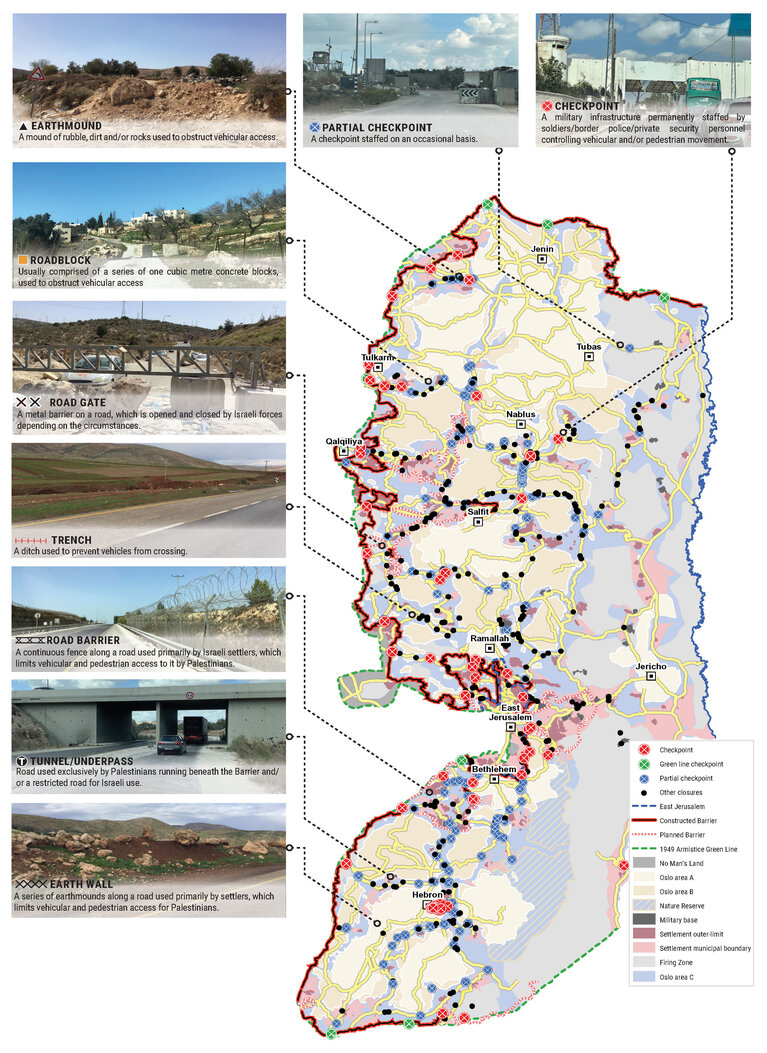

- In early 2023, OCHA documented 565 movement obstacles in the West Bank, including East Jerusalem and excluding H2. These include 49 checkpoints constantly staffed by Israeli forces or private security companies, 139 occasionally staffed checkpoints, 304 roadblocks, earth-mounds and road gates, and 73 earth walls, road barriers and trenches.

- Additionally, 80 obstacles, including 28 constantly staffed checkpoints, segregate part of the Israeli-controlled area of Hebron (H2) from the remainder of the city; many checkpoints are fortified with metal detectors, surveillance cameras and face recognition technology, and with facilities for detention and interrogation.

- Combined, there are 645 physical obstacles, an increase of about 8% compared with the 593 obstacles recorded in the previous OCHA closure survey in January-February 2020.

- Specifically, the number of occasionally staffed checkpoints has increased by 35% and that of road gates by 8%. While these remain open most of the time, they can be closed at any moment. In 2022 there were 1,032 instances (or 293 days) where nonpermanent checkpoints were staffed across the West Bank.

- Over half of the obstacles (339 out of 645) have been assessed by OCHA to have a severe impact on Palestinians by preventing or restricting access and movement to main roads, urban centres, services, and agricultural areas.

- In 2022, Israeli forces also deployed an average of four ad hoc ‘flying’ checkpoints each week along West Bank roads.

- In addition, the 712 kilometre-long Israeli Barrier (65% of which is built) runs mostly inside the West Bank. Most Palestinian farmers with land isolated by the Barrier can access their groves through 69 gates; however, most of the time, the Israeli authorities keep these gates shut.

- Palestinians holding West Bank IDs require permits from the Israeli authorities to enter East Jerusalem through three designated checkpoints, except for men over 55 and women over 50.

- In 2022, 15% of permit applications by West Bank patients seeking care in East Jerusalem or Israeli health facilities and 20% of permit applications for their companions were not approved by the time of the scheduled appointment. Also in 2022, 93% of ambulance transfers to East Jerusalem were delayed due to the ‘back-to-back’ procedure, where patients are transferred from a Palestinian to an Israeli-licensed ambulance at checkpoints due to restrictions imposed by Israeli authorities.

- Access to 20% of the West Bank is prohibited by Israeli military order on the grounds that the area is designated as a ‘firing zone’ for military training, or as a border buffer zone.

- Palestinians’ access to the about 10% of the West Bank lying within the municipal boundaries of Israeli settlements, is also prohibited by military order; many farmers can only reach their private land within or around settlements twice a year at most, subject to approval from Israeli authorities.1

- At the beginning of 2023, OCHA conducted a closure survey which revealed that there were 645 fixed movement obstacles deployed by Israeli forces, permanently or intermittently controlling, restricting and monitoring Palestinian movement in the West Bank, including East Jerusalem and the H2 area of Hebron. These physical obstacles form part of a range of restrictions that the Israeli authorities have imposed on Palestinians since 1967, including permit requirements and the designation of areas as restricted or closed. Combined, these restrictions impede access to services and resources, disrupt family and social life and undermine Palestinians’ enjoyment of their economic, social and cultural rights, undermine livelihoods and contribute to the fragmentation of the West Bank.

- The Israeli authorities continue to maintain direct control over the 20 per cent of Hebron, an area designated ‘H2’, which is home to some 39,000 Palestinians and a few hundred Israeli settlers.2 Access constraints include the deployment of 80 physical obstacles, a decline compared with the 101 obstacles recorded in the previous OCHA survey. This decline is mainly attributed to the amalgamation of existing obstacles and to some being judged to no longer constitute an obstacle. Additionally, 700 especially affected residents have been issued with special permits to access their homes through three designated checkpoints. This policy of movement restrictions has been guided by what the Israeli authorities have referred to as the ‘principle of separation.’ These restrictions have had a pervasive impact on Palestinians, who are limited in moving in and out of their homes, maintaining a family life and accessing livelihoods and services; alongside other occupation-related practices, they generate a coercive environment that places some of the affected families at risk of forcible transfer.

- The Barrier, in conjunction with its gate and permit regime, is the single largest obstacle to Palestinian movement within the West Bank. Where the Barrier is complete, most Palestinian farmers must obtain special permits or permission to reach the ‘Seam Zone,’ the land isolated between the Barrier and the Green Line. 69 gates have been designated for farmers’ access along the Barrier; however, they are mostly closed, with limited exceptions. Normally, the Israeli authorities only open them during the annual olive harvest, for short times each day. This has forced land owners to stop cultivation or to shift from labour-intensive to rain-fed and lower-value crops. About 11,000 Palestinians who live in the ‘Seam Zone’ and hold West Bank ID cards also depend on the granting of permits or special arrangements to continue living in their own homes and to maintain family and social relations with the remainder of the West Bank.

- The permit regime imposed since the early 1990s, and the construction of the Barrier in the 2000s, have progressively isolated East Jerusalem from the rest of the West Bank, transforming its geography, economy, and social life. These measures impede the access to East Jerusalem of Palestinians from any other part of the occupied Palestinian territory (OPT), including Gaza, whether they need to access services, including health care that is not available elsewhere, to visit holy sites, or to meet their relatives. The Barrier also severs densely populated Palestinian neighbourhoods within the municipal boundary of Jerusalem from the urban core, forcing their residents to take detours and cross checkpoints to access the rest of the city.

- Under international law, the Israeli authorities have the obligation to facilitate the free movement of Palestinians within the OPT, including East Jerusalem. Exceptions to this obligation are recognized only for imperative reasons of security and only in response to specific security threats. The sections of the Barrier running inside the West Bank, together with the associated gate and permit regime, are unlawful as concluded by the International Court of Justice.3

[1] https://www.emro.who.int/images/stories/palestine/WestBank_Health_Access_2022_infographic_final.pdf?ua=1

[2] https://ochaopt.org/content/humanitarian-situation-h2-area-hebron-city-findings-needs-assessment-april-2019

[3] International Court of Justice, Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, 9 July 2004.