The 2016 olive harvest: access challenges remain despite increase in permit approvals and reduced settler violence

The 2016 olive harvest season, which lasted from 15 October to the end of November, was reported to have proceeded relatively smoothly. However, sporadic incidents of settler violence and restrictions on access to olive groves behind the Barrier and near Israeli settlements continue to pose challenges for Palestinian farmers.

The 2016 olive harvest season, which lasted from 15 October to the end of November, was reported to have proceeded relatively smoothly. However, sporadic incidents of settler violence and restrictions on access to olive groves behind the Barrier and near Israeli settlements continue to pose challenges for Palestinian farmers.

The annual olive harvest is a key economic, social and cultural event for Palestinians. Approximately 183,000 hectares of land are cultivated for agriculture, nearly half of it for olive trees. Olive and olive oil production is concentrated in the north and northwest of the West Bank. Between 80,000 and 100,000 families are said to rely on olives and olive oil for primary or secondary sources of income, and the sector employs large numbers of unskilled labourers and approximately 15 per cent of working women. The entire olive sub-sector, including olive oil, table olives, pickles and soap, is worth between US$160 and $191 million in good years.[1] This year’s yield was poor and is projected to be 16,000-18,000 MT (metric tons) of oil, down from 21,000 MT in 2015 and 24,000 MT in 2014.

Decline in settler violence

Olive-based livelihoods in many areas of the West Bank are undermined by Israeli settlers uprooting and vandalizing olive trees, and by intimidation and the physical assault of farmers during the harvest season. Such incidents have declined in recent years, partly due to the enhanced deployment of Israeli military forces in sensitive areas around Israeli settlements. Nonetheless, a protective presence is still provided in some cases under the coordination of the Protection Cluster.

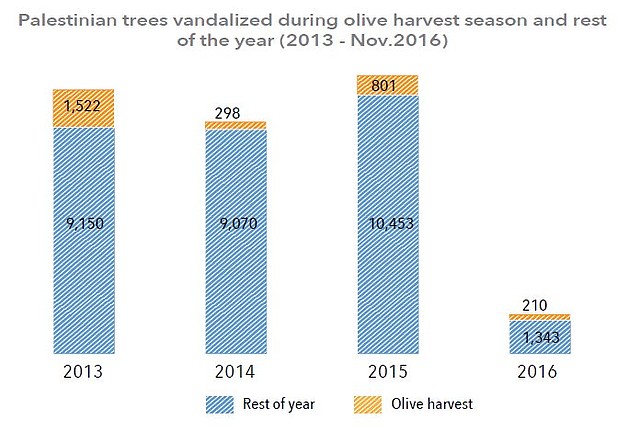

This olive season (October and November), OCHA recorded a total of 26 olive harvest-related incidents of settler violence resulting in property damage or injuries, down from 33 in 2015 and 29 in 2014. Some fifty per cent (13) of the incidents involved the vandalism of 210 olive trees (only during the olive harvest season). As in previous years, the majority of trees vandalized during 2016 were targeted outside of the olive harvest season when fewer Israeli forces are present. As illustrated in the chart, there was a major decline in the overall number of trees affected in 2016.

Preventive measures by international humanitarian organizations

For the fifth year in a row, the Protection Cluster, via the Core Group on Settler Violence chaired by the Office of the High Comissioner for Human Rights, coordinated the deployment of a protective presence to support Palestinian farmers and their families during the olive harvest. This year, 59 areas of friction were identified throughout the West Bank where settler violence has been recurrent. With the participation of 14 organizations, the Core Group on Settler Violence coordinated the monitoring and documentation of settler violence, developed and provided information and monitoring tools for volunteers, and ensured the referral of cases for protection (including legal and psycho-social) responses.

The Prior Coordination System

The presence of settlements restricts access to Palestinian land for cultivation purposes. Approximately 90 Palestinian communities own land within, or in the vicinity of, 56 Israeli settlements and settlement outposts. Farmers can only access their land through prior coordination with the Israeli authorities. Access is generally only permitted for a limited number of days during the harvest and ploughing seasons. This system was in force during this year’s olive harvest but, as in previous years, many Palestinian farmers complained that the period of time allocated was insufficient. In at least four cases this year, Israeli forces denied farmers access to their groves or prevented them from completing the harvesting of their olives. This resulted in farmers losing time from the already restricted schedule allocated.

In the Ramallah area, there were also reports that the Israeli army did not attend at the designated time and farmers felt insecure and vulnerable to attacks by settlers. In October, when farmers from Al Jaba’a and Beit Ummar accessed their 1,000 trees located within the Bat Ayin settlement security fence, they discovered that the majority of the trees had already been harvested.

Accountability for settler violence

The prevalence of Israeli settler violence, particularly the vandalism of olive trees, is closely linked to inadequate law enforcement by the Israeli authorities. During the 2013-2015 olive harvests, the Israeli organization Yesh Din documented a total of 53 harvest-related offenses: 10 related to crop theft, 25 to vandalism of trees and 18 to harvest disruption. Of these, 26 complaints were filed with the Israeli police, but only one resulted in an indictment. In 18 cases, the investigation was closed without an indictment, the majority (15) on the grounds of “offender unknown”.[2]

Increase in permits to access land behind the Barrier

The Barrier, the major obstacle to Palestinian movement within the West Bank, has a direct impact on olive-related livelihoods. Palestinian farmers need special permits or prior coordination to access farming land designated as a ‘closed area’ between the Barrier and the Green Line. If granted approval, farmers have to cross designated Barrier gates and checkpoints.

Most of the crossings along the Barrier are only open during the olive harvest period and only for a limited amount of time on those days, prohibiting year-round access. During this year’s olive harvest, 84 gates[3] were designated for agricultural access, of which only nine open daily, 10 open for some day(s) of the week and during the olive season; and the majority, 65, only open during the olive season. Of the 84 gates, 63 require access permits and 21 operate through prior coordination.

In the northern West Bank (Jenin, Tulkarm, Qalqiliya and Salfit governorates) where the majority of Barrier gates (44) are located and are the only crossings which open on a daily basis, the approval rate for permit applications increased from 46 per cent in 2015 to 58 per cent in 2016 to total 6,707 approvals. The number of applications also increased by 43 per cent from 8,024 to 11,498. However, over 4,700 applications by farmers for this olive harvest were rejected.

In Ramallah governorate where all 18 gates are seasonal, farmers complained of the lack of mid-day opening and of access at weekends when they could dedicate more time to harvesting the olives.[4] Most landowners reported that olive trees and land behind the Barrier were in very poor condition due to the lack of year-round access. The approval rate stood at 79 per cent, nearly the same as in 2015 and up from 67 per cent in 2014.[5]

In Jerusalem governorate, a total of 1,353 people applied for coordination to access their land behind the Barrier, up from 1,298 in 2015 and 887 in 2014. For the four gates that require permits, 129 people applied, of whom 75 received approval (58 per cent) and 54 were denied, primarily for security reasons.

In Bethlehem governorate, one of the three gates, Wad Dahshish/ Wadi Al Shami, did not open this olive harvest because farmers refused to provide ownership documents as a requirement to access their land behind the Barrier. In Hebron governorate, all seven gates require permits and were opened for three weeks from 26 October to 17 November. The vast majority of permit applications were approved.[6] However, a significant number of farmers owning land behind the Barrier who had been denied permits in the past refrained from re-applying this year.

Impact of access restrictions on olive productivity

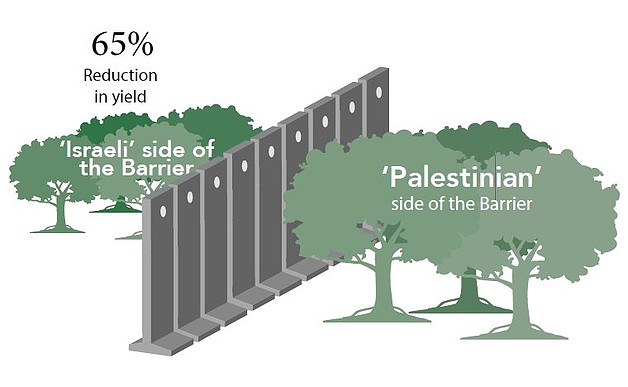

Access restrictions to land behind the Barrier and in the vicinity of settlements impede essential year-round agricultural activities such as ploughing, pruning, fertilizing, and pest and weed management. As a result, there is an adverse impact on olive productivity and value. Data collected by OCHA over the last three years in the northern West Bank show that the yield of olive trees in the area between the Barrier and the Green Line has reduced by approximately 65 per cent in comparison with equivalent trees in areas which can be accessed all year round.[7]

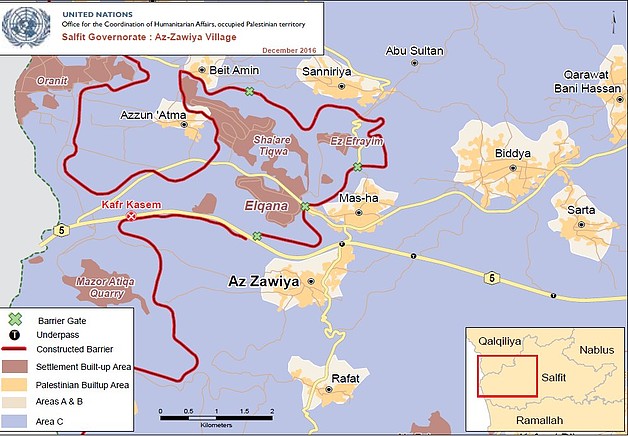

About 35 per cent of agricultural land in Az Zawiya village (Salfit) trapped between the Barrier and Elkana Israeli settlement

About 35 per cent (8,000 dunums) of the agricultural land of Az Zawiya (population 5,768), all planted with olive trees, is located in the seam zone behind the Barrier and within Elkana settlement boundaries.To access land in this area, Palestinian farmers must obtain a permit to cross the Barrier through the agricultural gate controlled by the Israeli army. They also need prior coordination to cross the fences surrounding the settlement.

About 35 per cent (8,000 dunums) of the agricultural land of Az Zawiya (population 5,768), all planted with olive trees, is located in the seam zone behind the Barrier and within Elkana settlement boundaries.To access land in this area, Palestinian farmers must obtain a permit to cross the Barrier through the agricultural gate controlled by the Israeli army. They also need prior coordination to cross the fences surrounding the settlement.

Khader Raddad and his family own six dunums of land (20 olive trees) behind the Barrier, and 15 dunums (250 olive trees) on the Palestinian side of the Barrier. In September 2013, at least 320 olive trees belonging to Az-Zawiya were completely burned in the seam zone. “The land is not ploughed and the grass is dry… throw a match and boom! All the trees are burnt,” said Khader.

OCHA has monitored the productivity of Khader’s olive trees for the past four years (see chart) by testing 10 trees on each side of the Barrier. This year, the 10 trees on the Palestinian side produced 150 kg of olives, while the ones on other side of the Barrier produced only 50 kg. Prior to the completion of the Barrier in 2004, Khader’s family was self-sufficient, but they now have to buy olive oil from the market to meet their needs

[1] PALTRADE, The State of Palestine National Export Strategy: Olive Oil, Sector Export Strategy 2014-2018, pp. 5-9. In a typical year, approximately 75 per cent of olive oil is absorbed by the domestic market, 14 percent is exported to Arab markets and eight per cent is exported to Israel.

[2] Five cases are still being investigated; two cases involved incidents documented by a different organization and Yesh Din has not been informed of their status. Yesh Din, Disruptions to the Olive Harvest in the West Bank, November 2016. According to Yesh Din, over 96 per cent of complaints filed with the Israeli police between 2005 and 2014 regarding deliberate damage to Palestinian-owned trees by Israeli settlers, and followed up by the organization, were closed without an indictment.

[3] This figure excludes the seven checkpoints not used to access agricultural land, but used by residents of the “Seam Zone” to reach workplaces and essential services in the rest of the West Bank.

[4] Gates opened between 13 and 25 October (nine days, excluding Fridays and Saturdays), twice a day, 07:30 and 17:00

[5] According to the Palestinian District Civil Liaison Office (DCL) and village councils, there were 1.047 applications in total in 2016.

[6] 520 out of 521 in the case of Idna and Khirbet Adair, and 284 out of 295 in the case of Deir Samet, Beit Awa and Deir Al Asal.

[7] For further details on the methodology used for data collection see Humanitarian Bulletin, February 2014, p 12.