Access to medical care outside Gaza

In June 2007, following the takeover of the Gaza Strip by Hamas and citing security concerns, Israel imposed a land, sea and air blockade on Gaza that intensified previous access restrictions. Along with the closure of the Rafah crossing by Egypt, the blockade ‘locked in’ nearly two million Palestinians in Gaza, unable to access the remainder of the OPT and the outside world. Exceptions are made for certain categories, including medical patients and their companions who must apply for a permit from the Israeli authorities to cross via the Erez crossing.

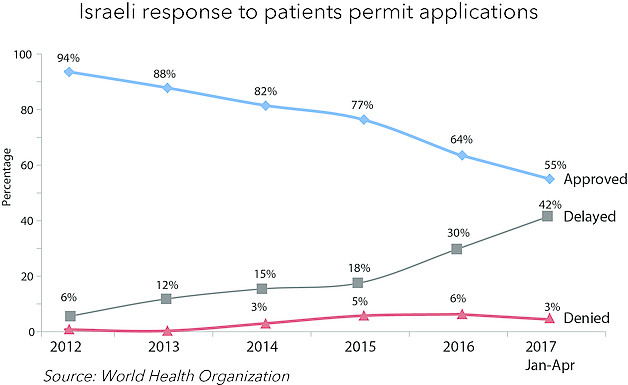

The number of exits via Erez started to rise after the 2014 hostilities and continued into 2016. However, numbers fell in the second half of the year, including a decline in the overall approval rate for medical patients to 64 per cent versus 77 per cent in 2015. The Israeli authorities have attributed the decline to concerns about the misuse of permits by Hamas.

The situation has been compounded by the ongoing internal Palestinian divide: since March 2017, the referral of over 2,000 patients for medical treatment outside Gaza has been disrupted following the apparent suspension of payments by the Ramallah-based Palestinian government. In April 2017, the World Health Organization reported that three patients from Gaza died while awaiting Israeli permits to access health care in hospitals in East Jerusalem.

The case of Siham al Tatari, Gaza City

January 2017: “The closure of Erez and Rafah crossings sentences cancer patients to death”

Siham,[1] a 53-year-old woman from Gaza and a mother of 10 children, was diagnosed with chronic lymphocytic leukemia in 2013. “This was the beginning of a long, painful and expensive journey,” Siham told OCHA in January 2017. Due to shortages in medical equipment in Gaza and because of difficulties in obtaining a permit for medical checks in East Jerusalem, Siham was referred to Egypt. There, she had to stay for three months, mostly at her own expense, as the Palestinian Authority covers the cost of medical treatment only. While in Egypt she contracted hepatitis C and only learned about it when she was back in Gaza a few months later.

“Last May (2016), I was put on chemotherapy as new cancerous tumors were found in my stomach and hips. The course of treatment ran for seven sessions that had to be completed without interruption every 21 days. I only managed two because the drugs were not sent from Ramallah to Gaza. I waited more than two months and then my doctor referred me to the Augusta Victoria hospital in East Jerusalem. Twice I missed my appointment because I lacked a permit. All I heard from the [Israeli] authorities was that the permit application was being processed. About five months after I first applied, and only after referring my case to human rights organizations and protesting, did I finally get a permit to leave Gaza. A day before coming to Jerusalem, I learned that the cancer has spread to the thyroid.

The repeated closure of Erez and Rafah sentences cancer patients to death. It’s a slow death. We are humanitarian cases. We demand our right to be treated.... We just want to be treated and go home. We are not dangerous or a threat to anyone’s security. We should have an open permit to avoid all the difficulties. The permit they give us is valid for one day only. If we encounter a checkpoint in Jerusalem, they send us back to Erez. A one-day permit is not enough.”

Published in January 2017 Humanitarian Bulletin

June 2017: “We want to receive treatment and be treated with dignity”

Five months later, the cancer had spread to Siham’s bone marrow. From January she returned to Augusta Victoria Hospital once and was put under a new course of four- to six chemotherapy sessions. She missed her 1 June appointment because she did not receive a permit and was still waiting to hear whether she would get one for her 11 June appointment.

“The permit application is still under consideration. I am worried I will miss my appointment again. My doctor told me I cannot have long interruptions between the sessions, and if I don’t make it for the next one I will have to restart the chemotherapy course all over again. I’m dreading it. If the bone marrow cancer spreads, it would necessitate a transplant. I don’t want to go down that road as it’s complicated and very risky. Timely treatment is important to try and stop or slow the cancer’s advancement. I just want to continue with the course without having to start all over again. The first session was exhausting. I felt so sick. On my way back home to Gaza, I fainted and lost consciousness while being searched at Erez. I need a companion but they need a permit, must be above a certain age and a first degree relative. The cost of having a companion with me in East Jerusalem is also unaffordable.

My doctor in Gaza says that having a positive outlook and high morale are important in dealing with cancer. How can I sustain morale when I’m struggling with the most basic of things such as having running water, being able to bake bread without electricity and finding the money to cover my medical treatment. Every time I have an appointment in Jerusalem my husband has to borrow money from his friends! How can I be positive when my university graduate children are unemployed and have no hope of finding a job? My house was damaged during the 2014 war and is yet to be fixed. I have nothing else to sell in the house to cover the transport costs. The recent PA salary cuts were the final straw: my salary has been cut by 40 per cent. I cannot repay the loans I have taken for my medical treatment or buy drugs for the other illnesses I have, let alone afford to buy the nutritious food that my doctor advised to me eat.

To be a cancer patient from Gaza is to be at the mercy of the occupation. It is being sentenced to a slow death by the permit regime, the harsh living conditions, the poverty, and the blockade. We just want to receive treatment and be treated with dignity. We want to live the little time left for us in dignity.”

[1] In the original case, Siham was referred to by the pseudonym Salma.