Closure of Barrier checkpoint triggers hardship and displacement in a Jerusalem community

The Barrier in the Jerusalem area has transformed the geography, economy and social life of East Jerusalem and its wider metropolitan area. In the areas where it follows the Israeli-defined municipal boundary, the Barrier physically separates Palestinian communities onto either side of what had previously been only a jurisdictional division. Thus, some Jerusalem suburbs that were once closely connected to the city are now walled out, with previously flourishing residential and commercial centres closing down, and families being forced to leave to areas with better access to services and livelihoods.

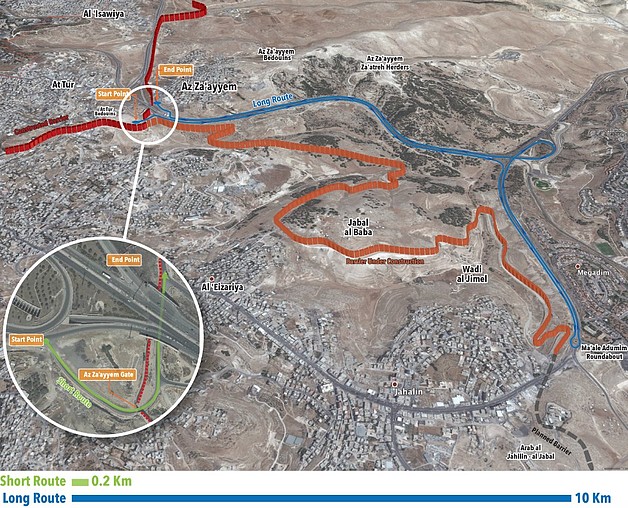

This is the case of Az Za’ayyem, a town located just outside Jerusalem’s municipal boundary.[i] It is estimated that over 80 per cent of its approximately 6,000 residents hold a Jerusalem ID card that, under Israeli law, entitles them to enter, work and receive services in Israel and East Jerusalem.[ii] Since September 2000, following the beginning of the Second Intifada, movement between Az Za’ayem and East Jerusalem has been gradually curtailed, culminating in 2005 with the completion of the Barrier in this area in the form of an eight metre-high wall. The resulting access restrictions were partially mitigated by a checkpoint installed on the intersection of the Barrier and the most direct route to the At Tur neighbourhood in East Jerusalem that allowed vehicular movement in one direction (from Jerusalem to Az Za’ayyem) around the clock.

In March 2015, the Israeli authorities replaced the checkpoint infrastructure with a metal gate. This was totally closed for the first two weeks and then started to open twice a day: for one hour in the morning and for three hours in the afternoon. Since October 2015, following a petition to the Israeli Supreme Court, the authorities added a third opening, increasing the cumulative opening time to eight hours a day.

Whenever the gate is closed, those returning from East Jerusalem must take a 10-km detour via the entrance to Ma’ale Adumim settlement. The detour extends the journey by 15 minutes for private vehicles and 30 minutes for trucks, with an additional 30-minute delay during rush hours, and increases transportation costs by up to NIS 750 a month per household.[iii]

Displacement

According to an assessment by the Az Za’ayyem village council, approximately 100 families, all Jerusalem ID holders, left the village in the year following the installation of the road gate and the new access restrictions to the main route into East Jerusalem. Overall, the net outflow from the village since the beginning of the access restrictions in 2000 is estimated at 240 families or 20 per cent of the existing population.[iv]

Commercial life

Depopulation resulted in an increase in the number of empty residential units and a related 30-35 percent drop in rental fees. Additionally, since April 2015, ten out of 60 shops in the village have reportedly closed down; those still operating have reported a sharp decline in revenues and an increase in transportation costs charged by their suppliers due to the long detour. The owner of a building materials workshop explained: “The closure of the gate paralyzed our commercial life. My sales dropped by 70 per cent.” The owner of a car repair facility added: “I had to lay off four workers, including one of my children, because my revenue has fallen significantly.”

Education

Around 400 children from Az Za’ayem who attend schools in the At Tur neighborhood in East Jerusalem now have now to take the detour when returning home outside of the opening hours of the Barrier gate. This requires them to cross a dangerous highway that has previously claimed the lives of a number of people. The closure also impedes access of children residing in At Tur and attending one of the four schools (three primary and one secondary) operating in Az Za’ayem.

Approaching the 12th anniversary of the ICJ advisory opinion

On 9 July 2004, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) issued an advisory opinion on the Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory. The ICJ recognized that Israel ‘has to face numerous indiscriminate and deadly acts of violence against its civilian population’ and that it ‘has the right, and indeed the duty, to respond in order to protect the life of its citizens. [However], the measures taken are bound nonetheless to remain in conformity with applicable international law.’

The ICJ stated that the sections of the Barrier route which ran inside the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, violated Israel’s obligations under international law. The ICJ called on Israel to cease construction of the Barrier ‘including in and around East Jerusalem’; dismantle the sections already completed; and ‘repeal or render ineffective forthwith all legislative and regulatory acts relating thereto’.

[i] Except for a small area located inside the municipal area.

[ii] These residents moved to the town from the 1970s onwards in search of accessible housing close to the city’s main employment, commercial and service areas.

[iii] Estimates submitted to the Israeli Supreme Court by petitioners against the closure.

[iv] This figure includes around 200 families who reportedly returned to the village between 2008 and 2015 to escape high rents in East Jerusalem.