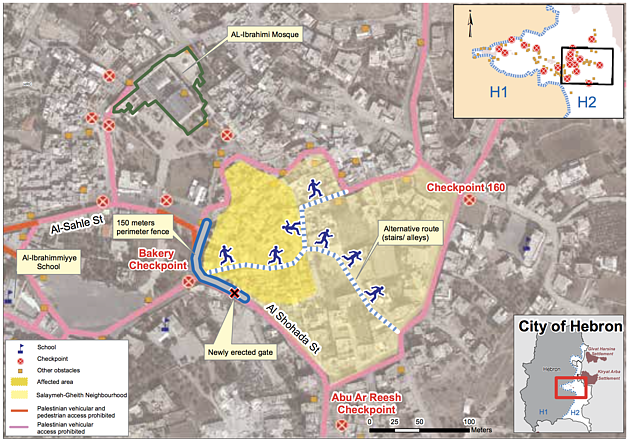

Further restrictions on Palestinian movement in the Israeli-controlled H2 area of Hebron city

A new fence installed by the Israeli authorities around two Palestinian neighbourhoods in the Israeli-controlled area of Hebron city (H2), As Salaymeh and Gheith, further separates up to 1,800 Palestinians from the rest of the city. This is in addition to the recent reinforcement (including the installment of turnstiles) of two pre-existing checkpoints controlling access to the area where the new fence was installed. These developments disrupt the livelihoods and family life of Palestinians living in the two neighbourhoods and limit access to basic services like health and education.

In May 2017, the Israeli authorities installed an approximately 50 meter-long and 1.5-meter-high metal bar fence on top of concrete slabs, with a gate, next to a metal fence initially installed in 2012 to surround As Salaymeh and Gheith. According to residents, Israeli Border Police manning the gate close it irregularly, without prior notice, leaving residents in a state of constant uncertainty. Israeli settlers are an additional source of friction and one resident reported people waiting at the gate being pepper sprayed by Israeli settlers driving by.

The additional section of the fence was reportedly installed in response to an incident on 4 May 2017, when a Palestinian reportedly attempted to stab Israeli soldiers near the adjacent “Bakery” checkpoint.

The fence and gate separate the residents from the main road connecting these neighbourhoods to the rest of the city and require additional walk to one of the nearby checkpoints out of the area (Abu Reesh or 160). Alternative exits from the fenced neighbourhoods involve longer paths, moving between houses or through narrow alleys and staircases. These routes are largely inaccessible to the elderly, people with disabilities and young children.

The main street behind the fence (referred to by Israeli settlers as ‘Prayers Road’) is used by Israeli settlers from Kiryat Arba settlement to access the Ibrahimi Mosque/Cave of the Patriarchs on foot or by car; Palestinian vehicular movement along this street is prohibited.

Some 600 children enrolled in schools outside the restricted area regularly use alternative routes between houses and alleys. This can add 1.5 kilometers to their journey and exposes them to friction with Israeli settlers and soldiers.

A student at the Ibrahimiyyeh Boys’ School, 13-year-old Farhat al Rajabi, explained: “My journey to school has become more difficult. I hate the gate. A few weeks ago I was arrested by the police after kicking the gate with my foot when the soldiers refused to open it for me.”

The new fence also impedes access to health facilities. The movement of ambulances in the restricted area needs to be coordinated through the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), who, in turn, coordinates with the Israeli authorities. Families from the two neighbourhoods need to cross the newly erected gate before reaching the ambulance. In one emergency case involving a woman bitten by a rodent, the gate was closed and the husband carried his wife through the alleys and between houses (involving stairs) to get her to a hospital.

The unpredictability of the closure discourages residents from leaving the area for social activities for fear of complications upon re-entering. This has exacerbated the sense of isolation, especially for women and children. Nuha al Rajabi, a 35-year-old mother of seven, explains:

“My house oversees the Ibrahimi Mosque and its compound. On many occasions, my rooftop was occupied by an Israeli army observation tower. They would enter my house without permission and in big numbers, creating fear and anxiety for me and my children. They recently vandalized my satellite dish. I am always afraid to leave the house for fear that they will break in. My family who resides in Jabal Joher cannot come and visit me. I haven’t seen my sick mother for two months since I visited her over Eid al Fitr for an hour. I couldn’t attend my brother’s wedding; I feel that I’m living in a cage.”

Area in Hebron city affected by new access restrictions

Pre-existing checkpoints reinforced

The fortification in mid-2016 of the two checkpoints (160 and Abu Reesh) that control access to the area with turnstiles and metal detectors also hampers the entry of commodities into the As Salaymeh and Gheith neighbourhoods, and to other neighbourhoods in the settlement-affected area of the city. Other measures have been imposed at these checkpoints, such as prohibiting men under 40 from entering on Fridays: a measure which was first implemented in 2015 and has become systematic since May 2016.

Previously, Palestinians used to unload trucks at the checkpoint and reload them onto carriages pulled by donkeys. Now Palestinians who need to move goods must coordinate in advance with the Israeli authorities to allow Palestinian-plated vehicles to cross checkpoint 160, enter the restricted area, download outside the gate, then carry the items by hand in small packs across the gate.

According to the Palestinian authorities, the coordination mechanism has allowed the entrance of construction material to renovate some houses in the area in Hebron Rehabilitation Committee projects. Nevertheless, the new arrangement is time-consuming, labor intensive, costlier and unreliable.

The livelihoods of families have been complicated. Na’el al Fakhouri (a father of six) stated that following the installation of the gate, his inability to bring in fodder for his cattle or necessary veterinary services was detrimental to his business.

“Before 2015 my main source of income was animal breeding: mainly sheep and goats. I used to bring in the fodder through checkpoint 160 on carriages pulled by donkeys. Now, after the fortification of the checkpoint and sealing off my house and neighbourhood with the gate, I no longer can bring in fodder or veterinary services. The number of animals has dropped from 120 to just 18. I started working as labourer in a local clay factory and my monthly income has dropped from 3000 NIS to 800 NIS.“

Background on the division of Hebron city

In January 1997, Israel and the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) signed the Protocol Concerning the Redeployment in Hebron. In the agreement, Israel handed over control of 80 per cent of Hebron city (18 km² known as H1) to the Palestinian Authority, while keeping full control over the remaining 20 per cent (H2). H2 includes four Israeli settlement compounds, home to a few hundred Israeli settlers and a population of over 40,000 Palestinians.

About 30 per cent of the Palestinians living in the H2 area (approximately 12,000) reside in neighbourhoods adjacent to the settlement compounds and are affected by strict access restrictions.[10] The Israeli authorities have premised the imposition of these restrictions on the need to protect its Israeli settler population located in these areas from Palestinian violence.

Currently, there are over 100 physical obstacles, including 20 permanently staffed checkpoints and 14 partial checkpoints that separate the settlement area from the rest of the city. Several streets within this area are designated for the exclusive use of settlers and are restricted for Palestinian traffic. In some streets, Palestinian pedestrians are banned. The coercive environment generated by access restrictions, along with systematic harassment by Israeli settlers, has resulted in the forcible transfer of thousands of Palestinians and a deterioration in living conditions of those who remain. A recent survey indicates that a third of Palestinian homes in the restricted area (1,105 housing units) are currently abandoned. Over 500 commercial establishments have been shut down by military order, and at least 1,100 others have been closed by their owners because of closures and restricted access for customers and suppliers.[11]

[10] Figures based on a 2015 survey conducted by the Hebron Rehabilitation Committee

[11] Report of the UN Secretary-General, Human rights situation in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including East Jerusalem, A/HRC/34/38, para. 28, 16 March 2017.