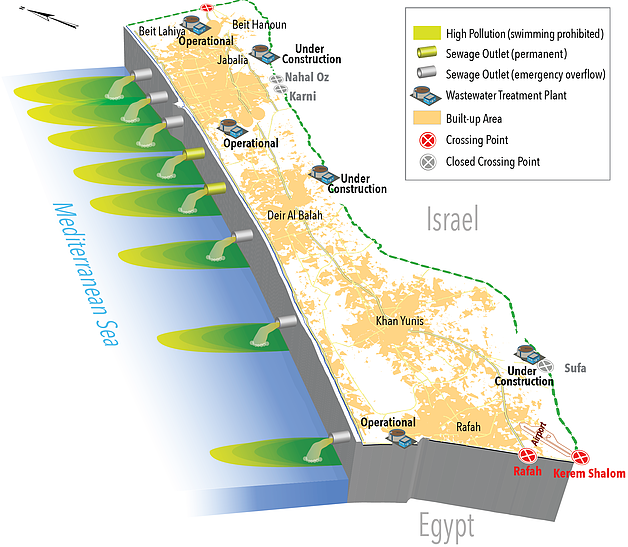

Gaza: shortage of sanitation infrastructure raises health and environmental concerns

In recent years, the longstanding shortage of adequate sanitation infrastructure in the Gaza Strip has resulted in the discharge of around 90 million litres of untreated or partially treated sewage into the sea every day, posing serious health and environmental hazards. Development of water and sanitation infrastructure has been severely impacted by the import restrictions imposed by Israel in its nine-year blockade of the Gaza Strip. At present, as many as 23 WASH items such as pumps, drilling equipment and disinfectant chemicals are on the Israeli “dual use” list, meaning that entry of such items to Gaza is severely restricted.

This situation is compounded whenever there is a reduction in the already limited electricity supply, which further impacts the quality of the sewage being released into the sea. Reductions in the electricity supply occurred extensively during April and May 2016 when the Gaza Power Plant (GPP) was shut down or operating minimally due to a shortage of fuel needed to run the plant, triggering up to 20 hours of blackout a day.[i]

The capacity of the Energy Authority in Gaza to purchase fuel to run the plant has been undermined since the beginning of 2016 following a change in the arrangement with the Ramallah-based Ministry of Finance to provide the GPP with a full exemption on fuel taxes. The scope of this tax exemption has been gradually reduced since January, significantly increasing the cost of fuel.

Seawater contamination and flooding risk

The contamination of seawater poses a serious health risk to those using beaches as recreational sites, particularly during the summer, and to those consuming seafood obtained from the areas most affected. A recent joint assessment by the Environment Quality Authority, the Civil Defence and the Ministry of Health in Gaza indicated that 52 per cent of the Gaza seashore is severely polluted and unsuitable for swimming, including nearly 90 per cent of the shore in Gaza City.

The precarious nature of existing facilities and power shortages also generates a constant threat of sewage flooding in areas adjacent to reservoirs and pumping stations. This threat materialized on 4 May 2016, when one of the retention walls of a sewage lagoon in Gaza City’s treatment plant collapsed following a prolonged power cut, releasing 15,000 cubic meters of raw sewage into a nearby farming area. Some 67 dunums of land planted with fruit trees were damaged as a result, with losses estimated by the Ministry of Agriculture at nearly US$150,000.

In another instance, on 13 November 2013, one of the main wastewater pumping stations in Gaza City (which handled 60 per cent of the city’s sewage) failed due to a lack of both electricity and fuel to operate backup generators. Over 35,000 cubic meters of raw sewage were discharged over a large area in the neighbourhood of Az-Zeitoun, affecting some 3,000 people.

Current and planned wastewater infrastructure

The Gaza Strip currently relies on four wastewater treatment plants that are working beyond their capacity and/or were constructed as temporary installations. The enormous capacity gaps, which are constantly increasing alongside population growth, are expected to be filled by three new treatment plants (in northern Gaza, Gaza City and Khan Yunis). The completion of these plants has been delayed for several years due to a combination of restrictions, including delays in construction permits and the entry of materials, plus shortages in energy capacity.

As a result of the severe electricity shortages, wastewater service providers (including the plants) rely heavily on back-up generators. However, this coping mechanism is constantly challenged by a lack of fuel, overuse, and impediments to the procurement of additional generators and spare parts classified as dual-use items. Part of the fuel needed to run generators is supplied via a multi-donor-funded emergency program coordinated by OCHA.

The effective treatment of wastewater will not only prevent seawater pollution but will also allow for the re-use of treated water for irrigation. This would contribute significantly to the preservation of the groundwater aquifer, which has been depleted to over-extraction, including by the agricultural sector.

[i] In recent years the GPP has operated at about half of its capacity and produces nearly 30 per cent (60 MW) of the electricity supplied to the Gaza Strip; the remaining electricity is purchased from Israel (120 MW) and Egypt (30 MW).