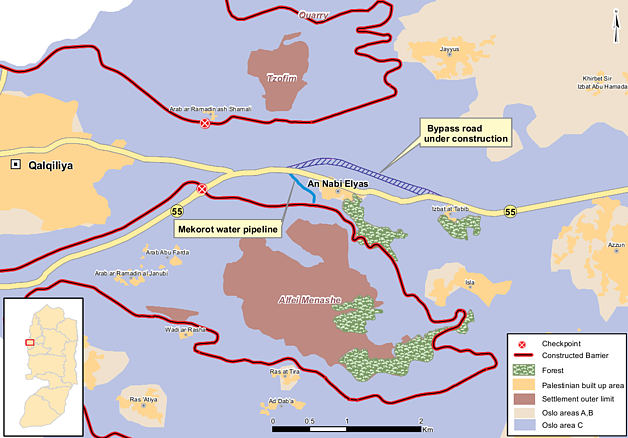

New bypass road in Qalqiliya area raises humanitarian concerns

The construction of a new 2.5 km-long road on Palestinian land is currently underway by the Israeli authorities; it will bypass a section of Road 55 running through An Nabi Elyas village (Qalqiliya). Construction has already had an impact on livelihoods and the property rights of the village residents (approx. 1,500), and the negative impact is expected to increase once the road is complete. At least two additional bypass roads are reportedly planned by the Israeli authorities along Road 60: one road is next to Huwwara village (Nablus) and the other is next to Al Arrub Refugee Camp (Hebron).

Road 55 connects the cities of Nablus and Qaliqiliya, and also connects the settlements of Qedumim, Ma’ale Shomron and Qarnei Shomron with Israel. According to the Israeli authorities, the large volume of traffic on Road 55, which passes through the built-up area of An Nabi Elyas village, generated a range of safety concerns and triggered the need for a bypass. An Israeli media report indicated that although the original plan for this road was approved over 20 years ago, the decision to implement it came in a 2015 agreement between the Israeli Prime Minister and an Israeli settler body (the Yesha Council).7

In December 2015, the Israeli authorities issued a confiscation order targeting 104 dunums of land for the planned road. The landowners joined with An Nabi Eliyas village council in a petition to the Israeli Supreme Court. This petition was rejected in November 2016 after the court found that the decision to build the road was based on “objective and professional safety considerations,” and that those considerations outweighed the damage caused to the petitioners.8 In January 2017 Israeli bulldozers began uprooting trees and leveling land.

Agricultural livelihoods

According to Palestinian sources, the land bulldozed exceeded 150 dunums in size, far above the 104 dunums cited in the confiscation order. This was apparently to secure the sides of the road; these were not included in the order. As a result, over 1,500 olive trees and about 100 fruit trees were uprooted. Farmers with available land were allowed to replant the trees elsewhere, while others used the trees for wood. For some of the farmers, the land expropriated was their sole source of income and the event triggered significant hardship (see case study). The cumulative loss from olive oil production is estimated at $104,000 per year.

Under Israeli military law, the landowners are entitled to compensation. However, Palestinian sources indicated that no farmer has submitted a claim, either as a matter of principle or due to fear of negative repercussions from within Palestinian society.

The road construction also disrupted a 1000-dunum land reclamation project costing $170,000, and which was launched in 2014 by An Nabi Elyas village council in collaboration with the Palestinian Ministry of Agriculture, the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and several NGOs. As part of the work for the bypass road, sections of the 10,000 metres of water pipes and the electricity grid installed for the reclamation project were damaged. The Israeli authorities promised that the damage would be rectified but the precise date remains unknown.

Farmers have expressed concerns that once complete, the road will impede their access to cultivated land located to the north of it, despite the current construction by the Israeli authorities of an underpass which will connect this farming area to An Nabi Elyas village and mitigate the impact of access impediments.

Commercial livelihoods

The location of An Nabi Elyas along a major road serving Palestinians cities and Israeli settlements, and its proximity to Arab localities inside Israel, has led to the development of a dynamic commercial life, which became a major source of livelihood for its residents. There are currently some 100 commercial establishments, including a variety of shops, garages and restaurants. Village council officials have raised concerns that the diversion of traffic from the village will significantly reduce the volume of customers, undermine livelihoods and reduce municipal tax revenues, which support service provision.

Urban development

The core of An Nabi Elyas built-up area is designated as Area B (90 dunums), where the Palestinian Authority holds planning authority, but the margins of the village and the broader surrounding areas are defined as Area C, where the Israeli planning regime applies. Space available in the latter area for urban development has been reduced gradually over the years: in the south, the village is blocked by the Barrier and the Alfie Menashe settlement; to the west there is an Israeli water infrastructure where construction is banned; and to the east there is a “registered forest”, also preventing development. The new bypass road will bisect the space left to the north, between the village’s built-up area and the Barrier surrounding Tzofim settlement.

On 1 April 2017, the Israeli Civil Administration (ICA) invited objections (a step prior to final endorsement) of an outline plan for An Nabi Elyas in Area C that would encompass some 360 dunums. This would protect existing homes and businesses in this area from demolition and would allow for additional development. This would be the sixth plan out of approximately 100 for Area C submitted by the Palestinian Authority to the ICA in the past six years which has been approved.

Farmer loses all his land to the bypass road

Standing on a piece of leveled land, with no trace of olive trees or anything but a wide road under construction, Salah Majjad, a 45-year-old father of six from An Nabi Eliyas, tells the story of his loss:

“The four and half dunums of land I own, where I stand now, has been confiscated for

the construction of the bypass road. The plot of land was my sole source of income. It had about one hundred olive trees, a few almond and fig trees, and vines. The type of olive trees I had was not large and this allowed us to make use of the land between the trees to grow other fodder crops for animals and chickens. We even grew lentils and chickpeas sometimes. My wife and I used to go to the land and tend it almost every day. The money we made from our produce was just about enough for the whole year.

Since the loss of my land, I have been working as a taxi driver. I have heart problems and cannot do hard manual work. I had to use my private car as a taxi, although this is not authorized and puts me at risk of receiving a fine if I am caught by the Palestinian police. To buy a registered taxi is very expensive and there is no way I can afford it,” said Salah.