New legislation impedes challenges to demolitions and seizures in the West Bank

In recent months, the Israeli authorities have passed or advanced new legislation that will significantly limit the ability of individual and human rights organizations to challenge the demolition or seizure of Palestinian properties in Area C and East Jerusalem.

The demolition and seizure of homes and other service and livelihood-related structures is a key component of the coercive environment exerted on Palestinians in parts of the West Bank.[1] These actions are carried out on the grounds of lack of Israeli-issued building permits, which are nearly impossible to obtain. Less than one per cent of Area C and about 13 per cent of East Jerusalem are covered by an approved planning scheme for Palestinians, which is a pre-condition for a permit to be issued, and most of these areas are already built up.[2] At present there are over 13,000 demolition orders pending against Palestinian structures in Area C according to an Israeli Civil Administration (ICA) database. In East Jerusalem, it is estimated that up to a third of the city’s Palestinian population, or some 100,000 people, reside in unlicensed buildings.

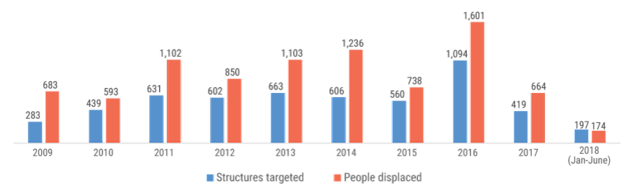

In the first half of 2018, the Israeli authorities demolished or seized 197 Palestinian-owned structures in Area C and East Jerusalem. This is nearly the same monthly average as in 2017. These incidents displaced 174 people and otherwise affected nearly 5,000.

Expediting demolitions and seizures in Area C

On 17 April 2018, the IDF commander in the West Bank issued a military order allowing the demolition of unlicensed structures in Area C deemed as “new” within 96 hours of a removal notice being issued.[3] Following petitions filed with the Israeli High Court of Justice (HCJ) by humanitarian partners providing legal assistance, the Israeli authorities announced in June 2018 that they would freeze implementation pending a decision by the HCJ.

Structures targeted and people displaced-totals

According to the military order, “new structures” are those identified by an ICA inspector as having been built within the previous six months, or inhabited for less than 30 days prior to the removal notice. The only way to prevent the demolition is to produce a valid building permit or provide evidence that the targeted structure is not “new” within the meaning of the order.

The new order severely restricts the right to a hearing or the opportunity of appeal. According to the planning regulations applicable in Area C, the first enforcement measure against an unlicensed structure is a stop-work order, which gives the owner 30 days to object and try to obtain a building permit retroactively. If this fails, the ICA may issue a final demolition order, usually due for implementation within two to four weeks, during which period the owner may petition the HCJ and potentially obtain an injunction freezing the demolition order pending a ruling.

While it may still be possible to petition the HCJ under the new order, additional legislative initiatives (see below) seek to limit this possibility. In any case, the available window of opportunity (96 hours) may make this option unrealistic in practice.

The new military order follows an amendment to an earlier military order of November 2015 which has a similar effect.[4] The amendment allows the ICA to seize, without any formal advance notification, structures determined by an ICA inspector as “mobile” and installed no more than 60 days prior to the seizure. “Mobile structures” are understood as those which can be disassembled or otherwise removed without destroying them. Originally reported as a measure for use against settlement outposts, since mid-2017 it has been implemented in Palestinian communities. For example, in June and August 2017, the Israeli authorities dismantled and seized 96 solar panels and six caravans to be used as classrooms, both provided as humanitarian assistance and funded by international donors, in Jubbet ad Dhib, an Area C community in southern Bethlehem.[5]

Expediting demolitions and impeding legal recourse in East Jerusalem

On 25 October 2017 the Israeli Parliament (the Knesset) approved a range of amendments to the 1965 Planning and Building Law, which applies to both Israel and occupied East Jerusalem. These amendments are expected to expedite demolitions and limit access to legal recourse. The application to old residential buildings has been postponed for two years, circa October 2019, if there are ongoing legal proceedings related to previous demolition orders.[6]

Prior to these amendments, the Jerusalem municipality could issue an administrative demolition order valid for only 60 days. After the expiry of this period, it was possible to indict the builder and, if proved in court that the building had been built illegally, a judicial demolition order would be issued that initiated a relatively lengthy legal process. Under the new law, building inspectors themselves can summarily issue an administrative demolition order, and the period within which an administrative order remains valid was extended to six months (i.e. tripled).[7]

Additionally, if the case reaches court and a judicial demolition order is issued, under the new law the court can postpone its execution only for limited specified reasons and only twice, for a maximum of six months each time, before the court deems the demolition case to be essentially closed.[8]

Under the new law, fines imposed on individuals charged with building without a permit can reach up to NIS 400,000 rather than the previous penalties of tens of thousands of shekels.

Restricting access to the Israeli HCJ

Additional proposed initiatives would restrict access to legal avenues to the HCJ. A bill debated by the Knesset in May 2017 seeks to bar individuals and organizations not directly and personally harmed by a government action from petitioning the court. Later that year, a member of the Knesset Constitution, Law and Justice Committee also proposed to triple the submission fees applicable to HCJ petitions from NIS 1,786 to 5,400 for Palestinians or organizations representing them.[9]

If approved, the first initiative would block NGOs from challenging practices and regulations on the basis of principle, while the second would increase the cost of legal assistance, restricting the ability of organizations to adopt new cases.

On January 2018 the Israeli Ministry of Justice published a draft bill calling for jurisdiction over petitions presented by Palestinians against the Israeli authorities to be transferred from the HCJ to the Administrative Affairs Court. The bill was approved the following month by the Ministerial Committee for Legislation, paving the way for the Knesset to vote on it in the near future. Unlike the HCJ, the mandate of the Administrative Affairs Court is limited to procedural issues and it does not adjudicate on matters of constitutional or international law.

These recent legal initiatives on HCJ access will make it harder for Palestinian petitioners to seek protection from events, such as demolitions or confiscations, increasing their humanitarian vulnerability.

[1] See OCHA, “Palestinians at risk of forcible transfer”, in OPT Humanitarian Facts and Figures, December 2017, p. 18.

[2] In comparison with over eight per cent planned for the construction of settlements, which are illegal under international law.

[3] IDF Order 1797 concerning the removal of new buildings (Judea and Samaria), 2018.

[4] IDF Regulations on the transfer of goods (Judea and Samaria), 1993.

[5] In November 2017, following a petition to the Israeli HCJ and vigorous protests by the donor, the solar panels were returned to the community.

[6] Old residential buildings that do not meet this condition (i.e. ongoing legal proceedings) will be considered as new buildings.

[7] This would in effect reduce the burden on courts of handling demolition cases and give greater weight to building inspectors. Court rulings on cases of judicial demolition orders will now include orders for the municipality to implement a demolition, whereas in the past it was primarily imposed on the party that had committed the building violation.

[8] Following this, a second indictment is issued against the building owner for contempt of court that could take up to 12 months to challenge. The third and final indictment entails sentencing the owner to an obligatory prison sentence. Also see 3.1.

[9] Sue Surkes, “Coalition of MKs seeks to triple costs of High Court petitions for Palestinians”, Times of Israel, 28 November 2017.