Recent trends in Palestinian access from Gaza: Erez and Rafah crossings

Palestinians in Gaza who wish to exit the enclave can only do so through the Israeli-controlled Erez crossing or the Rafah crossing, which is controlled by Egypt. The Erez crossing is vitally important as it controls the movement of people between Gaza and the West Bank via Israel. Since the early 1990s, Palestinian residents of Gaza have required an exit permit to leave through Erez. Under a policy implemented since the beginning of the second Intifada in September 2000 - and tightened after June 2007, citing security concerns, following the takeover of Gaza by Hamas - only people belonging to specific Israeli-defined categories are eligible for an exit permit, subject to a security check.

The vast majority are not eligible to apply for an exit permit. In recent years, those eligible have included patients referred for medical treatment outside Gaza and their companions; traders; staff of international organizations; and exceptional humanitarian cases. This policy has exacerbated the isolation of Gaza from the remainder of the OPT and the outside world, further limiting access to medical treatment unavailable in Gaza, to higher education, to family and social life, and to employment and economic opportunities. The realization of a range of human rights is thus impeded.

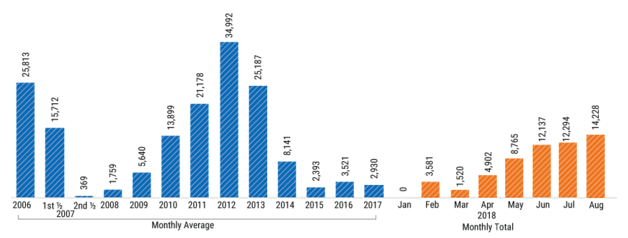

The average number of Palestinians allowed to exit Gaza through Erez per month so far in 2018 (January-August) has risen compared with 2017 (9,376 versus 6,900) but is still below the monthly average for 2016 (13,187) and 2015 (15,027). Prior to the start of the second Intifada in 2000, there were over half a million exits per month from Gaza, primarily for work in Israel; this was totally halted in 2006. Since 19 August, citing continued violent incidents at the perimeter fence, Israel has intermittently imposed additional restrictions on the movement of Palestinians at Erez crossing.

Due to longstanding restrictions associated with the blockade at Erez crossing, Rafah crossing became the primary exit point to the outside world. Political uncertainty and military operations in northern Sinai led Egypt to impose severe restrictions on the crossing from October 2014 through to mid-May 2018. Since then, there has been a significant improvement and Rafah crossing has been open almost continuously.

Gaza patients continue to face barriers to access through Erez

This article was contributed by World Health Organization

On 26 August 2018, the Israeli Supreme Court unanimously accepted a petition from Israeli and Palestinian human rights organizations, submitted on behalf of seven patients needing to use Erez crossing through Israel to access healthcare unavailable in Gaza. The court ruled that the decision by the Israeli Security Cabinet in 2017 to deny Gaza patients access to medical treatment as a means of leverage over Hamas, and solely on the basis of the patients’ relationships to Hamas members, was ineffective, counters the values of the State of Israel and is illegal.

Israeli responses to Gaza patient permit applications

The seven patients were all women who had applied for permits to access healthcare in East Jerusalem. Four of the women needed treatment for cancer, specifically for radiotherapy and chemotherapy not available in Gaza. The other three patients had applied for access to complex neurosurgical treatment with surgical expertise and equipment unavailable in Gaza hospitals.

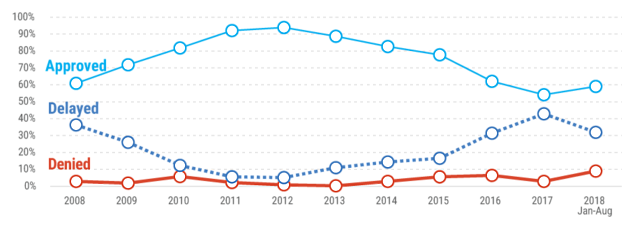

Patients needing medical treatment, surgical procedures or diagnostic procedures outside Gaza have faced significant barriers to accessing healthcare since Israel introduced its patient permit system in 2004. Since 2012 the approval rate for patient permit applications has fallen significantly from 93 per cent in 2012 to 54 per cent in 2017 (see Chart 1). In the first half of 2018, the approval rate improved slightly and 59 per cent of applications were approved. One in 10 applications (nine per cent) were denied and almost a third (32 per cent) were delayed, with patients receiving no definitive response to their applications by the date of their scheduled hospital appointment.

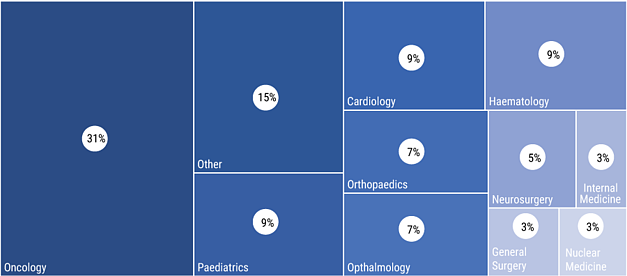

The majority of patient referrals from Gaza are to hospitals in the West Bank, principally to the major referral centres in East Jerusalem that provide specialized health services unavailable elsewhere in the OPT. These include Augusta Victoria Hospital, the main cancer referral centre, and Makassed Hospital, a major destination for surgical and paediatric referrals. In addition to access barriers, recent reductions in funding to the East Jerusalem hospital network risk the sustainability of critical specialist health services for Palestinian patients. Cancer is the single largest reason for referral, accounting for nearly a third (31 per cent), with paediatrics (health treatment for children), haematology (blood disorders) and cardiology each representing a further nine per cent of all referrals.

Men generally face more restrictions than women, with men aged 18 to 60 experiencing the lowest approval rates. The highest approval rate by gender and age is for women aged over 60 at 79 per cent in 2017. Men aged 18 to 40 had the lowest approval rate of only 30 per cent of applications in 2017.

Distribution of referrals by speciality

Patients who require permits to access health treatment outside Gaza must navigate an opaque and often unpredictable application process. The majority of patients who are denied permits or delayed access to treatment and diagnosis are given no specific reason for their refusal. Patients requiring longer courses of treatment can be separated from their friends and family for months, with the costs of travel to access care an additional burden on families. Patients and their companions are called for security interrogation as a prerequisite to the Israeli authorities processing their permit applications. In the first half of 2018, 111 patients (78 male; 33 female) and 35 companions (27 male; 8 female) were summoned for security interrogation.

Rafah: an unpredictable gateway

The Egyptian-controlled Rafah crossing, the only crossing for passengers between the Gaza Strip and Egypt, has been open continuously since May 2018, except for holidays and special occasions. This is the longest period of continuous opening since September 2014 when the crossing was closed. Prior to May 2018, the crossing opened for only a few days a year, reportedly due to concerns about security in the Sinai. Despite the improved access since May 2018, over 23,000 people are still registered on a waiting list (that numbered approximately 30,000 previously) according to the Ministry of Interior (MoI) in Gaza.

Rafah: Crossings in both directions

Registration lists

The procedures regulating the exit of people via Rafah are confusing and obscure. According to an official in the Palestinian Authority Border and Crossings Authority, there are two lists for permitted travelers: the first issued by the Hamas-affiliated MoI as part of the electronic pre-registration process, and the other a list coordinated by the Egyptian authorities. This has raised allegations of the payment of bribes in Gaza and in Egypt to ensure travel and a faster response. This would seem to be the case since May 2018 as some people who have been registered for up to eight months have not yet been approved to travel while others who registered only one month before have already travelled.

During the sporadic openings of the Rafah crossing prior to May 2018, an average of some 650 people per day were allowed to exit, but in recent months the daily average has fallen to 343.

Travelling pathway

According to the Palestinian Border and Crossings Authority, once passengers traveling from Gaza to Egypt finish all the procedures on the Palestinian side of the crossing, they move to the Egyptian side where lists of names are sent to the Egyptian authorities for approval. The approval response takes between one to eight hours. Some passengers do not receive an answer and have to keep waiting or return to Gaza. The waiting period for these procedures applies to all passengers, even patients.

The buses arrive outside the Egyptian side of the terminal, where passengers need to wait for up to three hours for security checks. Under normal conditions the journey to Cairo should take 5-7 hours (around 450 km) but it currently takes over 12 hours due to the many checkpoints deployed on the road to the ferry in Port Said, which links the east and west banks of Egypt. The night curfew imposed by the Egyptian authorities in Sinai prolongs the journey and frequently forces people to spend the night at the Rafah crossing.

The return

At the ferry checkpoint to cross the Suez canal, a long line of vehicles waits but the ferry only moves when it is full. Even when the ferry is full, people may have to wait for security reasons. To get on the ferry, a reservation should be made for a vehicle but some drivers reportedly pay bribes to secure a place in the front line. On the ferry, passengers undergo a very strict search process that lasts several hours.

After crossing to the canal, the passengers need to cross through several checkpoints. At each checkpoint, the luggage is carefully searched. When travellers returning to Gaza arrive at the Egyptian side of the Rafah crossing, the same checks are resumed.

Case study: “I just wanted to be rid of the pain”

Hanan is 42 and lives in Deir-al-Balah refugee camp. She is a mother of seven children and was diagnosed with a pituitary tumour in November 2017 after suffering from headaches and blurred vision. Her doctors in Gaza referred her for neurosurgery outside Gaza because of the lack of adequate equipment and skills to perform this kind of specialized surgery locally.

Hanan is 42 and lives in Deir-al-Balah refugee camp. She is a mother of seven children and was diagnosed with a pituitary tumour in November 2017 after suffering from headaches and blurred vision. Her doctors in Gaza referred her for neurosurgery outside Gaza because of the lack of adequate equipment and skills to perform this kind of specialized surgery locally.

“I applied for a permit to go to Makassed Hospital in East Jerusalem six or seven times but I was denied each time and lost my appointments. I was getting worse during this time and I couldn’t function properly or take care of my children. The last denial came a few days before the Eid feast and I cried because I just wanted to be rid of the pain and the torture. We appealed through al-Mezan Center for Human Rights and they took the case to the Israeli High Court. I can’t describe how I felt when I learned that the petition had succeeded.”

When Hanan reached Makassed Hospital, the doctors discovered that the surgery would be more complicated than expected because the tumour had grown:

“My doctor said there was a high risk that the surgery might damage my vision, but I had no other choice but to go ahead. I was alone at Makassed Hospital for eight days, although people in the same room as me helped me when I needed to eat or drink. I stayed a total of 10 days there and in the last two days my sister-in-law finally received a permit to come and help me.”

Hanan is now back in Gaza recovering from her operation but has not yet seen any marked improvement in her condition.

“I lost the vision completely in my right eye and I can hardly see with my left eye. It’s hard for me to recognize people at the moment, but my children are helping me a lot.”

A four-day journey from Cairo to Gaza

Forty-three-year-old Rana from Rafah travelled to Amman to visit her family whom she had not seen for five years. She spent two months in Amman and returned to the Gaza Strip on 6 September via Rafah crossing.

“The way back was extremely exhausting and involved sleep deprivation and hunger. I was travelling for four days; I slept one night at the ferry and one night in the Egyptian hall at Rafah. The ferry is unsuitable for sleeping; you cannot even find a bathroom and you are constantly mistreated by the Egyptian officers. We were stopped at dozens of checkpoints on the way back and at every one, our luggage was unpacked and searched.

“When we arrived at Rafah, the crossing hall was closed. We begged the Egyptian officers to open so we could sit and go to the bathroom. They only allowed us in after four hours. The hall was full of rubbish. We slept on the ground and on the very hard chairs. Everything is expensive at the crossing but I was lucky that I was not stuck in Egypt as that would have been much more expensive. Overall, we spent 21 hours at the crossing."