Survey identifies 19,700 housing units beyond repair and 24,000 requiring prioritized shelter assistance

This article was contributed by the Shelter Cluster

The number of housing units in substandard conditions across the Gaza Strip increased dramatically since mid-2014 as a direct result of hostilities that took place that year. Nearly four years later, over a third of the homes that sustained some type of damage (some 59,000 out 171,000) are yet to be repaired.[1] This has been compounded by the devastated infrastructure which is the main cause of recurrent flooding during the winter rains.[2] High levels of unemployment and poverty are key reasons preventing families from repairing or maintaining their homes, whether damaged during hostilities or degraded by routine use.[3] Repairs and maintenance, including of infrastructure, have been limited by the Israeli restrictions on the entry of building materials.[4]

During June, the Shelter Cluster released its housing vulnerability survey in the Gaza Strip which assesses the prevalence of substandard housing conditions and the levels of household vulnerability, while examining the correlation between housing vulnerability and poverty.

The survey included a representative sample of 1,170 households. Two dimensions of housing vulnerability were measured: shelter vulnerability (physical/technical) and household vulnerability (social). For the first dimension, housing units were assessed against 30 minimum criteria, including exposure to risks and hazards, the condition of external and internal walls, roofs and windows, safe access, connectivity to the water network and the functioning of sanitation facilities.[5] To examine the level of household vulnerability, the homes were mainly assessed on general information regarding the number of nuclear families in each unit; events affecting the housing units, such as hostilities and natural disasters; the availability and condition of furniture and equipment; and type of employment and income.

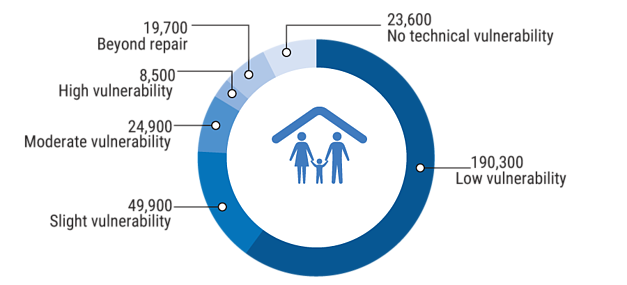

The survey found that 92.5 per cent of the households surveyed were affected by some kind of shelter vulnerability. Of these, 6.2 per cent, or the equivalent of 19,700 housing units, were classified as beyond repair, meaning that full reconstruction is needed. These will be referred to the Ministry of Housing, UN agencies and NGOs involved in reconstruction. Some 10.5 per cent of the homes (equivalent to 33,000 housing units) were classified as either moderately or highly vulnerable. The remainder, 75.8 per cent, fell within the low and slight vulnerability categories. Of the approximately 33,000 housing units that are moderately or highly vulnerable, 24,000 are believed to require a prioritized shelter response.

Projected Number of Vulnerable Households in the Gaza Strip

Of note, around 70 per cent of households included in the sample reported that some form of damage had been sustained during the 2014 conflict, and 51 per cent (partially overlapping with the previous group) reported that their homes had been damaged during previous hostilities or as a result of floods and winter storms.

Furthermore, the substandard housing conditions are a concern in the event of massive displacement due to a new round of hostilities or a natural disaster, as over 20 per cent of the households surveyed (the equivalent to 65,000 housing units) reported that they have hosted IDP’s in the past.

Shelter vulnerability is a source of concern, not only for physical safety, but also for its impact on health and wellbeing, including putting residents at risk of exposure to the elements, increased mental health issues, raised risk of domestic violence, and low educational attainment.

Response to shelter needs

Humanitarian partners are working to provide assistance to the most critically vulnerable families, for whom basic interventions can make a dramatic difference in the safety, health and dignity of housing. Humanitarian support, however, only alleviates the most egregious elements of substandard shelter and is not a replacement for sustainable solutions. For this, humanitarian partners look to their counterparts in development to provide wider-range of support to the moderately and lightly vulnerable categories.

Humanitarian partners responding to these shelter needs support shelter upgrades and provide non-food items and temporary assistance such as plastic sheets, blankets, hygiene and kits, with or without shelter upgrading. Referrals to specialized agencies are also made, where appropriate. The latter includes cases requiring reconstruction or cases where legal barriers are present such as lack of sufficient ownership documentation, living on government property or inheritance-related hurdles.

Between January 2017 and June 2018, the Shelter Cluster carried out projects to upgrade some 1,110 substandard shelters. Available funds are sufficient to cover a shelter response for only an additional 1,100 housing units of the some 24,000 in need, placing lack of funding at the forefront of challenges hampering responses by the Shelter Cluster.

Case Study: Family lives in an unfinished house for over a decade

Forty-six-year-old Mahmoud Abu Shallouf lives together with his 45-year-old wife, Um Hasan, and their 10-year-old daughter and two sons (ages 6 and 17) in a 120 square metre un-finished concrete-built home constructed on governmental land in Ezbet Beit Hanoun, one of the most marginalized localities in the northern Gaza Strip.

The family are registered Palestine refugees, and receive UNRWA food parcels on a quarterly basis. The father is the only current bread winner. During the week, he works transporting building materials and other items such as food, animal feed and gas cylinders, occasionally selling vegetables from his donkey cart. At weekends Mahmoud used to work as a security guard. His wife runs the household and their 17-year-old son is searching for a job as a plumber following training at an UNRWA vocational training centre.

The family started the construction of their house some 10 years ago but their limited income is consumed mainly by spending on food and drinking water, leaving hardly anything for the house. This has resulted in their inability to plaster the walls and some rooms have no ceiling. There is almost no furniture, blankets, mattresses, a floor mat. There is no door to the entrance or to any of the rooms, and no electrical equipment such as a refrigerator, gas stove or washing machine.

“I’m always afraid that somebody will sneak in through the windows” said Um Hasan.

The house was only recently connected to the sewage network but is still unconnected to the water or electricity network. To cope, Mahmoud fills a 500-litere tank with water he takes from his father’s water line and uses the neighbour’s electricity line.

Over the past decade, the family managed to cover the roofs of three bedrooms with a metal corrugated sheet; the bathroom is covered with only a thin concrete slab, and the living area, kitchen and corridors with a mixture of cloth, nylon, and palm fronds. The floor coverings are equally inadequate and most of the windows lack protection or screens. The bathroom has no shower and the kitchen is in adequate for preparing food hygienically.

“I’m always worried about my family” said Mahmoud. “In the winter the house is very cold and the kids cannot study properly. We made a tent outside the house and build a fire to create a warmer place to study in”

These conditions have had negative physical and psychological impacts on the family. Reptiles and insects pose a threat, and the family are constantly exposed to the elements. Last winter, the family could not use most of the house because the sand floor became too wet and cold to be used as a living space.

[1] For a full breakdown of houses destroyed and damaged and their status see: Shelter Cluster Factsheet of May 2018, accessed here.

[2] For more details, see the Humanitarian Bulletin of November 2017, titled, Poor infrastructure and lack of funding put over 560,000 people at risk of flooding in the Gaza Strip. Available here.

[3] See UN OCHA Humanitarian Bulletin, May 2018 edition, pages 8-11. Accessed here.

[4] These limitations mainly relate to items the Israeli government classifies as ‘dual use’ meaning that they have both civil and military usages. The entry of such items is contingent on Israeli approval, which is required separately for each type of restricted item, in addition to approval for the project in principle. Since the beginning of 2017 approvals for the entry of dual use construction materials (primarily cement and metal bars) via the Gaza Reconstruction Mechanism (GRM) have increased significantly in comparison with previous years. However, applications for other restricted items have either been rejected completely or faced long delays. See here more information on the GRM.

[5] For full list kindly refer to Inter-Agency Shelter Survey on Substandard housing conditions in Gaza, June 2018, accessed here.