Three years on from the 2014 conflict, 29,000 people remain displaced

The hostilities between Israel and Palestinian armed groups from 8 July to 26 August 2014 were the most devastating in the Gaza Strip since the start of the Israeli occupation in 1967. They resulted in the deaths of 2,251 Palestinians, including at least 1,462 civilians, and 71 Israelis, of whom five were civilians. Over 11,000 Palestinians were injured, including hundreds of people left with a long-term disability, and huge numbers of the population, particularly children, were traumatized. The destruction or severe damage of some 17,800 housing units left approximately 100,000 people displaced. Gaza’s infrastructure, businesses and agricultural land also sustained significant damage. Three years on, most of Gaza’s population is still struggling with the aftermath of the conflict to varying extents.

Serious violations of international humanitarian law by both sides occurred during the hostilities but accountability has remained elusive. Israeli criminal investigations into alleged violations of the laws of war led to the prosecution of soldiers in one case of looting.[2] No meaningful investigations have been carried out by the Palestinian authorities.

Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs)

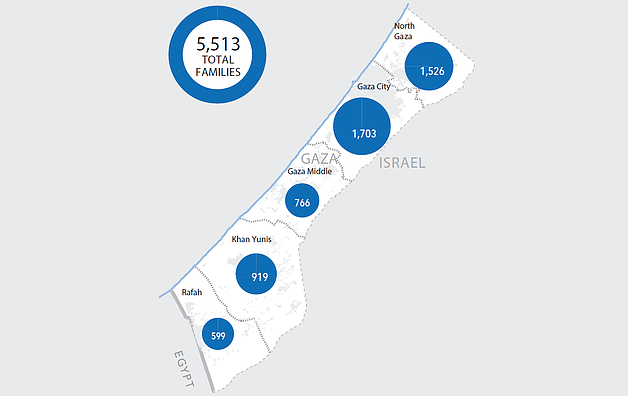

Based on the cases registered by the IDP Working Group (see background box), some 29,000 (over 5,500 families) of the 100,000 people displaced at the end of the conflict were still displaced at the end of August 2017. The homes of approximately one third of those still displaced (9,800 people) are currently being reconstructed, while the other 19,200 IDPs have not been allocated any funding for reconstruction and see no end in sight to their displacement.

Lack of funding is the primary reason for ongoing delays in reconstruction. According to the Palestinian Authority’s National Office for Gaza Reconstruction, only two thirds of the approximately $500 million needed for the reconstruction of totally destroyed homes have been disbursed, as of July 2017.[3]

To a lesser extent, reconstruction has been also slowed down due to restrictions on imports of basic construction materials into Gaza, imposed by Israel citing security concerns. However, restricted materials have been entering regularly via the temporary Gaza Reconstruction Mechanism (GRM) agreed in 2014 by the UN, the Palestinian Authority and Israel. [4]

According to the IDP Working Group, the majority of IDPs (88 per cent) reported that they were residing in rented accommodation, with the others remaining in or next to their damaged homes (7 per cent), with relatives (3 per cent), or in makeshift shelters/ caravans (2 per cent). Given the limited housing stock, it is believed that some of the families in the first category are in fact renting space in the homes of their extended families or in units not intended for residential use.

The housing shortage in Gaza continues to be an issue of concern. An OPT UN Country Team report highlighted that the housing shortage has increased from 71,000 housing units in 2012 to 120,000 today, mainly due to natural population growth alongside the conflict-related reconstruction efforts [5]

Temporary shelter cash assistance (TSCA) of $200 to $250 per month per family has been the primary form of assistance provided by the humanitarian community to eligible families, enabling families to rent accommodation until their homes are reconstructed or rehabilitated. The distribution of TSCA has been disrupted due to significant funding shortages: UNDP, which is expected to cover some 500 IDP non-refugee families, has not distributed any TSCA since the beginning of 2017, while UNRWA, which is responsible for some 4,500 displaced refugee households, exhausted its cash reserves for this response in June 2017.

Another 450 non-refugee families from the Ash Shujaiyeh area of Gaza city have been receiving payments from the Palestinian Red Crescent Society (PCRS) as part of a one- year-project funded by Turkey, due to end in December 2017. Currently UNDP needs $1.5m and UNRWA needs $4m to cover their caseload through 2017.

Uncertainty about interruptions to TSCA has generated fears of eviction and further relocation by families unable to afford rental payments. Anecdotal evidence collected by humanitarian partners supporting IDPs indicates that the interruption of TSCA has resulted in debt accumulation and the adoption of negative coping mechanisms such as withdrawing children from school to cut expenses and/or engaging children in income generation. Such cases are referred to the Education or relevant cluster for assistance.

200,000 children still in need of psychosocial support

* This section was contributed by UNICEF

The trauma experienced during successive hostilities, combined with ten years of Israeli blockade and internal Palestinian divisions, have taken their toll on the resilience of the two million people who live in the coastal enclave, half of whom are children.

An assessment conducted by UNRWA in May 2017 as part of its Community Mental Health Programme on the well-being of Palestinian adult and child refugees, concluded that 30 per cent of young children are experiencing serious issues, such as hyperactivity (restlessness, fidgeting or easily distracted) and emotional symptoms (being unhappy, scared or worried). Around 48 per cent of adults attending UNRWA clinics experience “poor wellbeing”.7 Both children and parents reported emotional problems, many of which they attributed to conflict, the blockade and Palestinian divisions with ramifications on electricity supplies.

In 2016, the Humanitarian Needs overview (HNO) identified 235,633 children in need of child protection services including psychosocial support. This number has decreased only marginally (3 per cent) in 2017. Those in need include vulnerable children living in the Access Restricted Area (ARA) near the fence with Israel, internally displaced persons (IDPs), and children from the most marginalized, socio-economically vulnerable and underserved communities across the Gaza Strip.

In 2016, child protection and psychosocial support services provided by 29 organizations reached about 195,400 children (83 per cent of the target for 2016). In the first half of 2017, 42,500 children (19 per cent of the target) were reached. Services include individual case management, structured group and individual psychosocial support, life skills education, child-parent interaction programmes, expressive arts, Explosive Remnants of War (ERW) risk education, and sports and recreational activities.

One of the significant challenges is the political division between the administrative authorities in Gaza and the West Bank. This contributes to the humanitarian crisis and falling levels of humanitarian funding that undermine response capabilities.

Protection Cluster services provided and funding levels for 2016 and 2017

Source: HRP 2016 and 2017, FTS OCHA

The IDP working group (IDPWG)

Hardships faced by displaced Palestinians in long-term residence in caravans

During the 2014 hostilities in Gaza, Khader al-Masri and his wife and children moved out of their home in Beit-Hanoun and sought refuge for one night at an UNRWA school in the same area. They then moved to Jabalia, as shelling intensified, where they stayed in another UNRWA school until the ceasefire, 51 days after the beginning of the hostilities. The family returned to their home in Beit-Hanoun but found it completely destroyed, as a result,they reverted to a new UNRWA school “collective center” in Beit-Hanoun. After making five moves between UNRWA and public schools, the family was provided with two caravans by the Palestinian ministry of Works in mid-October.

Khader is currently unemployed and completely dependent on UNRWA assistance for food provided to those classified by UNRWA as suffering from abject poverty. He described living in the caravan as a “deadly solution. The place is suffocating, reptiles get into the caravan and dig holes, and the temperature is very high in summer and very low in winter”. Khader’s nephew who resided in a caravan was killed when the caravan door fell on him, his sister-in-law miscarried and his brother suffered burns to his hand as a result of electricity short circuits. In another incident, part of the caravan’s roof collapsed onto Khader’s children, no one was injured.

Khader’s seven children (aged between 1 and 12 years of age) suffer from skin problems caused by mosquitos and other insects. Water piped from the municipality comes once every three days so drinking water has to be purchased and the electricity is switched off for fear of deadly short- circuits.

Khader’s children suffer from psychosocial stress and their academic achievement has fallen significantly: several of them are failing classes in subjects in which they were previously performing well.

In fact, Khader explained that his daughters have refused to return to school after the summer because they did not have school uniforms or backpacks. He said that he had been desperately seeking someone to loan him money for the school equipment.

“We hope that winter never comes and we don’t like the summer”, Khader said. One of his daughters added,“Winter is very cold and we cannot move, and in summer it is burning hot and we cannot breathe”.

With support from UNRWA, and after the delay of reconstruction due to ownership issue, Khader may get his house rebuilt in the near future. Although the house will be smaller in size, conditions for the family will improve drastically. Khader’s case was also referred to organizations who are attempting to provide the necessary support for his daughters to be able to attend school

[2] Latest figures from Military Advocate General 24 August 2016 (in Hebrew only).

[3] Information provided by the Shelter cluster in August 2017.

[4] The GRM has facilitated imports of 2.3 million tons of construction materials (cement, aggregate and rebar). Nearly 120,000 people whose homes were damaged or destroyed have purchased cement through the GRM. Almost 380 large-scale construction projects have been completed through the GRM and another 330 are underway.

[5] UNCT, Gaza Ten Years Later, July 2017.

[6] See OCHA, Gaza: Internally displaced persons, April 2016.