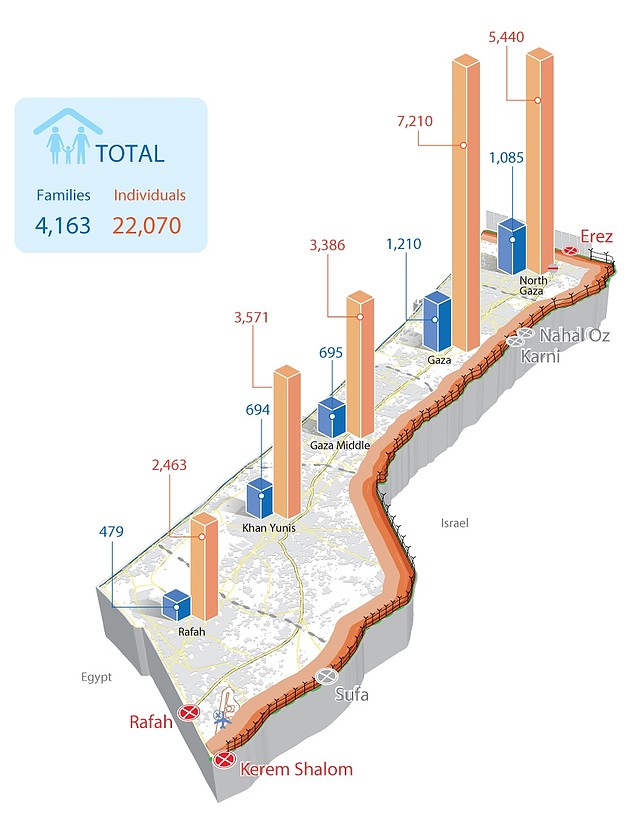

22,000 people in the Gaza Strip still internally displaced from the 2014 hostilities

The hostilities between Israel and Palestinian armed groups from 7 July to 26 August 2014 were the most devastating in the Gaza Strip since the start of the Israeli occupation in 1967. In addition to the 1,460 Palestinian civilians killed, including 556 children,[1] some 17,800 housing units were destroyed or severely damaged, causing approximately 100,000 internally displaced persons (IDPs). Three and a half years after the ceasefire, more than 22,000 people (4,162 families) are still displaced (as of the end of February 2018).[2] As highlighted below, many of them continue to live in precarious conditions with uncertainty regarding their immediate future.

Lack of funding is the primary reason for the slow pace of reconstruction: approximately two-thirds of remaining IDPs have not received any housing support and see no end in sight to their displacement. The homes of the other third are either still under construction or waiting for work to start. Reconstruction has also been hampered, to a lesser extent, by Israeli restrictions on imports of essential construction materials into Gaza. Despite these delays, restricted construction materials have been entering regularly via the Gaza Reconstruction Mechanism (GRM) agreed in 2014 by the UN, the Palestinian Authority and Israel.

New vulnerability survey

During November and December 2017, the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) carried out a vulnerability survey to inform humanitarian interventions to support IDPs.[3] A total of 1,179 IDP households were surveyed, of which nearly 30 per cent were pre-identified as vulnerable, while the remaining 70 per cent were selected at random.[4]

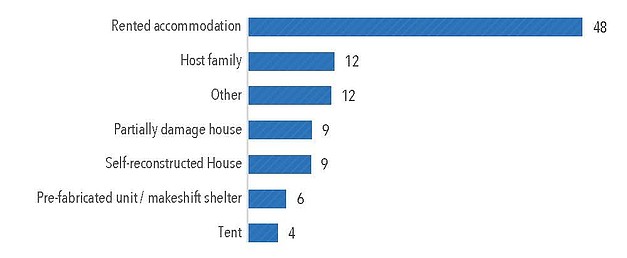

Nearly half of the households surveyed reported living in rented accommodation, followed by 18 per cent living in damaged or partially reconstructed (without funding) homes, and 12 per cent were staying with extended or host families.

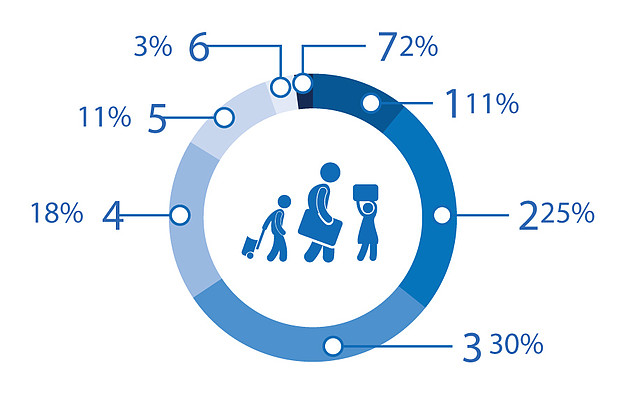

The level of overcrowding is particularly high: almost 30 per cent of surveyed families reside in a one-bedroom shelter and another 36 per cent in a two-bedroom shelter. Overcrowding is likely to be a significant factor behind the high levels of gender-based violence (GBV) reported: 49 per cent of surveyed households indicated that displacement had led to an increase in the level of GBV in their families, and 42 per cent reported an increase in violence against children at home.

Temporary shelter cash assistance (TSCA) of US$200-$250 per month per family has been the primary form of assistance provided by the humanitarian community to eligible families, enabling them to rent accommodation until their homes are reconstructed or rehabilitated. However, the distribution of TSCA has been constantly disrupted due to funding shortages.

This is reflected in the survey’s findings, in which only 41 per cent of surveyed families reported receiving TSCA on regular basis; 13 per cent were uncertain about their current eligibility; and the rest had had their payment stopped or had never received any. Of concern, most families reporting that their TSCA had been discontinued indicated that they did not know the reason.

Current IDPs by governorate

Inability to pay rent is one of the main drivers of the constant relocation of IDP families. Among the households surveyed, 65 per cent reported that they had relocated between three and ten times since their initial displacement in 2014. Additionally, 35 per cent reported that they are currently not living in their original neighbourhood or area. Many of these families indicated that displacement has had a negative impact on their access to livelihood opportunities, schools and health services.

Current accommodation (percentages)

In addition, 64 per cent of heads of households were not working at the time of the survey, well above the unemployment rate of 43.6 percent for the Gaza Strip as a whole during the fourth quarter of 2017.[5] Coping mechanisms include selling assets, purchasing food on credit and reducing dietary diversity. This is of a particular concern for pregnant and lactating women, of whom nearly 20 per cent indicated that they were consuming food that was inappropriate for their needs.

Number of relocations since 2014

The disbursement of funds pledged by donors for the reconstruction of Gaza following the 2014 hostilities is the main step required to move towards ending prolonged displacement and reducing the vulnerability of IDPs. In the meantime, it is essential that UNRWA and other agencies are adequately funded to maintain the TSCA programme and provide IDPs with the minimal means necessary to maintain their current accommodation. Keeping IDP households better informed about their entitlements and the ongoing challenges to provision of assistance is also essential to reduce vulnerability.

“All I wish is to have iftar with all my children at one table.”

The house of Marwan Kishko, a 62-year-old with hearing difficulties, in the Az Zeitun area of Gaza city, was almost totally destroyed during the 2014 hostilities. “I have lived with my wife and children in this house for 32 years. After the war we settled in a tent near the rubble of my house for two months, and after receiving cash assistance we moved to a rented apartment. However, the rental cash assistance was cut almost a year ago, I believe because lack of funds.”

Marwan’s wife, Umm Wael, added: “I prepared all the documents in the hopes that we would receive financial assistance to rebuild our home quickly. We submitted the request in March of 2016 and so far have received no answer. We keep waiting but could not afford the rent for the apartment and moved back to our damaged house. But you cannot call this a house. The walls cannot be repaired. The roof is made of corrugated steel sheets supported by iron bars. One evening, a wild dog entered the house and threatened me. I was terrified. All I wish is to have a house before the holy month of Ramadan so I can have iftar with all my children at one table.”

[1] Five Israeli civilians, including a child, were also killed over the course of the 2014 hostilities.

[2] Estimate from the IDPs Working Group led by OCHA and the Shelter Cluster.

[3] This survey was intended to update a re-registration and vulnerability profiling survey carried out in the second half of 2015 by the IDP Working Group under OCHA’s coordination and which targeted 16,000 IDP households. For the main findings see here.

[4] Households were considered particularly vulnerable if they were headed by a female, an elderly person or a child; if they had one or more member with a disability; or if they were residing in caravans or makeshift shelters.

[5] Although these two figures are indicative of the high prevalence of unemployment among IDPs, they are not fully comparable: to be considered unemployed in labour statistics, a person must be actively seeking a job during the reporting period, which is not necessarily the case for all heads of household covered in the IDP survey.