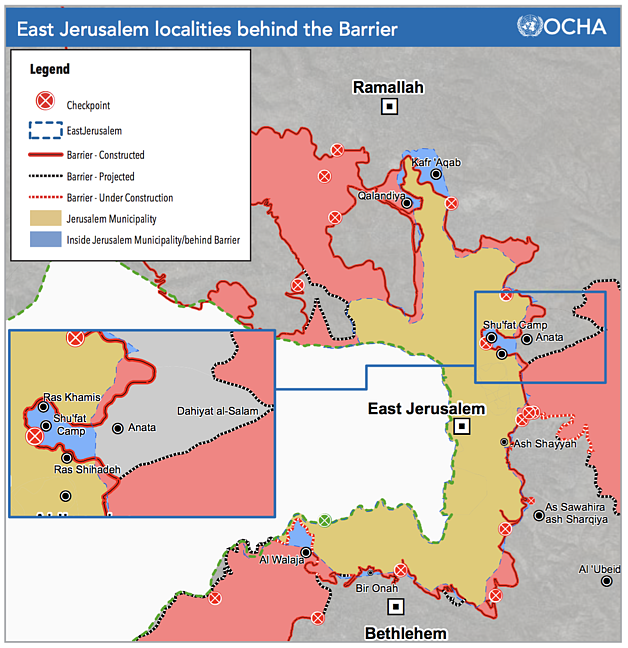

East Jerusalem Palestinian localities behind the Barrier

The Barrier physically separates some East Jerusalem Palestinian localities from the urban centre, despite these areas remaining inside the Israeli-declared municipal boundary and residents retaining their permanent resident status in the city. Palestinians living in these areas now need to cross checkpoints to reach workplaces and the health, education and other services to which they are entitled as residents of Jerusalem.

The two localities primarily affected are Kafr ‘Aqab and the Shu’fat Camp area, (the latter comprising Shu’fat Camp, Ras Khamis, Ras Shihadeh and the Dahiyat al-Salaam area of Anata). Smaller enclaves include Ash Shayyah, Qalandiya village and part of As Sawahira Ash Sharqiya. Also affected are Bir Onah and part of Al Walaja in the Bethlehem governorate, which were incorporated by Israel within the municipal boundary of Jerusalem in 1967 (See map).

The population of these areas is estimated to total 160,000, although the ratio of East Jerusalem residents to West Bank ID holders is also unknown. Kafr ‘Aqab, in particular, is the location of choice for couples with ‘mixed residency’ status; spouses who hold Jerusalem residency can maintain their ‘centre of life’ and live with their West Bank partners without obtaining a permit for the partner to live in these areas, which have effectively been abandoned by the Israel authorities.

Lack of services, facilities and security

Although residents of these areas continue to pay municipal taxes, the public infrastructure, resources and services are significantly degraded or lacking entirely. Road are unpaved and lack sidewalks, street lighting or pedestrian crossings.[1] On some occasions, as in Ras Khamis, residents have paid for the upkeep of their own roads.[2] Water and sewage systems are stretched and fail to keep pace with the growing population.[3] Basic services, including garbage collection, are contracted out by the municipality to private companies based on an underestimate of the actual number of residents, creating significant gaps. In Shu’fat Camp this has led to the regular burning of garbage and other environmental hazards.[4]

The Israeli police seldom enter municipal areas beyond the Barrier except for “security reasons”. However, under the Oslo Accords, the Palestinian Authority is formally prohibited from operating in these areas, thereby creating a security vacuum manifested in an increase in lawlessness, crime and drug trafficking.[7] Israeli ambulances do not enter these areas, requiring Palestinian ambulances to coordinate the transfer of patients at checkpoints. [8]

Jerusalem Envelope Community Authority

In 2005, Israel established a ‘Jerusalem Envelope Community Authority’ to provide an optimal response to essential needs and ensure that the Palestinian localities separated from the city by the Barrier continue to receive state and municipal services. “The State also promised to fund special transportation for all students living outside the Barrier, to establish a community administration, to build new schools and rent classrooms, to allocate municipal hotlines, and to arrange alternative traffic routes for residents of the neighbourhoods and for rescue teams in the event of an emergency.” [5] However, according to the Association for Civil Rights in Israel, “in spite of a government decision that was made a decade ago, and in spite of commitments the government made following legal petitions to the High Court of Justice, as of today, none of the multitude of assurances made to the residents of these neighbourhoods have been fulfilled.”[6]

Wildcat construction

Due to the restrictive planning regime in East Jerusalem, there is a serious housing shortage; those who build ‘illegally’ face the threat of demolition, displacement and other penalties. A notable aspect of the Palestinian localities behind the Barrier is the rapid and informal increase in residential construction, particularly high-rise buildings. This construction is driven by the lack of municipal enforcement and an absence of the penalties and demolitions meted out to Palestinians in the rest of the city.[9] The phenomenon is most evident in the two large enclaves of Kfar ‘Aqab[10] and the Shu’fat Camp area, but smaller areas such as Ash Shayya and Bir Onah are currently experiencing a similar boom in construction.

The massive demand for housing has led to unauthorized construction and dangerous practices: buildings constructed within metres of each other without adequate infrastructure for water, drainage, sewage, electricity and roads. In Shu’fat Camp, makeshift overhead electricity cables and water lines have been installed by residents, increasing security hazards. The lack of municipal oversight to ensure basic engineering and safety standards is particularly evident in the lack of contingency planning for earthquakes and other hazards.[11]

[1] “In Kafr ‘Aqab, only four kilometres out of the total 25 kilometres of roads are paved and in reasonable condition”, Ir Amim, “Displaced in their own city”, p.35.

[2] “Palestinian neighbourhood, abandoned by Jerusalem, paves Its own road”, Ha’aretz, 12 April, 2016

[3] In March 2014, the water supply to Shu’fat camp and neighbouring areas was disconnected for weeks. The authorities explained that the infrastructure had not been expanded to keep pace with the sharp rise in population and that the majority of homes had been constructed without a permit. In January 2015, the Supreme Court ruled that the authorities must upgrade the existing water lines in order to increase the water pressure and that meetings should be held with residents to arrange payments for water. Ir Amim, “Displaced in their own city” pp. 33-34.

[4] Ibid. In Shu’fat camp, UNRWA is responsible for sanitation collection, but residents of neighbouring communities dump their garbage in the camp for UNRWA to collect, overburdening the Agency’s capacities. In Ash Shayya, Al ‘Eizariya Municipality collects the garbage although it is formally prohibited from operating in the area, which falls under the jurisdiction of the Jerusalem Municipality.

[5] Ir Amim, “Displaced in their own city”, p.37.

[7] “Refugee Camp near Jerusalem becomes a haven for drug dealers”, Ha’aretz, 21 November 2011

[8] According to Al Eizariya Municipality, if a Jerusalem resident dies in the Ash Shayya enclave, the body must be transported to Ma’ale Adumim checkpoint where an Israeli health official in an ambulance confirms the death and issues a certificate before the death is officially recognized by the Israeli authorities.

[9] In recent months, the Israeli authorities have started to demolish some structures in these communities, most recently 15 low-rise structures in Qalandiya village on 27 July.

[10] As of 2012, the number of new building start-ups in Kafr ‘Aqab accounted for 83 per cent of all new building in the entire city of Jerusalem. As of the beginning of 2013, some 1,282 new apartments were nearing completion, all in high-rise buildings. Ir Amim, “Displaced in their own city”, p. 44.

[11] Employees from the Building Inspection Division have not entered Kafr ‘Aqab since 2005. Ibid, p.46.