Gaza’s health sector struggles to cope with massive influx of casualties amid pervasive shortages

This article was contributed by The World Health Organization

In the wake of the ‘Great March of Return’ demonstrations since 30 March, Gaza’s already overstretched health sector has been struggling to cope with the mass influx of casualties. This burden has exacerbated the long-term shortage of medicines and limited capacities of health facilities, driven by the huge electricity deficit and the ongoing salary crisis affecting government employees, among other reasons.

Health cluster partners have responded to meet the increased health needs arising from injuries during the demonstrations. On each Friday since 30 March, the MoH, along with the Palestinian Red Crescent Society (PRCS), have established ten medical trauma stabilization points (TSP) next to the five tent camps, to stabilize injuries before referring them to nearby hospitals. Also, more than 260 ambulances and 650 paramedics[1] and first responders have been on standby, in addition to the deployment of further trauma and surgical teams, with at least 20 international health staff deployed since the onset of the demonstrations, and the provision of essential and much needed medicines and medical equipment.

Health cluster partners have responded to meet the increased health needs arising from injuries during the demonstrations. On each Friday since 30 March, the MoH, along with the Palestinian Red Crescent Society (PRCS), have established ten medical trauma stabilization points (TSP) next to the five tent camps, to stabilize injuries before referring them to nearby hospitals. Also, more than 260 ambulances and 650 paramedics[1] and first responders have been on standby, in addition to the deployment of further trauma and surgical teams, with at least 20 international health staff deployed since the onset of the demonstrations, and the provision of essential and much needed medicines and medical equipment.

Many of the injured suffered extensive bone and tissue damage from gunshot wounds, requiring very complex surgeries. Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) reports: “apart from regular nursing care, patients will often need additional surgery, and a very long treatment program of physiotherapy and rehabilitation. Many patients will have functional deficiencies for the rest of their life. Some patients may yet need amputation if not provided with sufficient care in Gaza, or if they are unable to obtain the necessary authorization to be treated outside of the strip.”[2] According to data from the Palestinian Ministry of Health (MoH) and the Salama Society in Gaza, between 30 March and 23 May there have been 34 amputation cases, including 27 lower limbs and six upper limbs amputations.[3]

Due to the number and gravity of the injuries, the stocks of medical supplies have significantly depleted and access to healthcare for non-trauma patients is being compromised. The occupancy rate for surgical wards at the European Gaza Hospital, for example, was approximately two and half times the number of surgical patients it ordinarily has the capacity to accommodate,as of 16 May.

This situation is replicated across Gaza, where non-surgical wards have been converted to surgical wards to cope with the influx of trauma patients. In Ministry of Health (MoH) hospitals, all appointments at outpatient clinics (over 2,000 patients per day), as well as all elective surgical procedures (over 100 patients per day), have been cancelled. The average waiting time for an ear-nose-throat surgery at Shifa, Gaza’s largest hospital, for example, is currently estimated at more than a year.

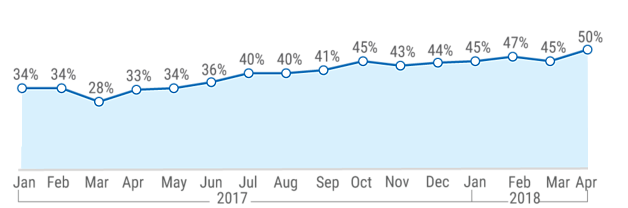

Percentage of drugs at Zero Stock level

(less than a month of stock)

Furthermore, according to Gaza’s Central Drug Store, 40 per cent of essential medicines were totally depleted by end of April and another 10 per cent of medicines and 29 per cent of disposables had less than a month’s supply remaining.[4]

Since the start of the current events, as of 27 May, 71 truckloads carrying medical supplies have entered Gaza, including three through the Egyptian-controlled crossing of Rafah, donated by the Egyptian Red Crescent, and 68 through the Israeli-controlled crossing of Kerem Shalom, supplied by ICRC, UNICEF, MoH, UNRWA and the private sector. In addition, Israel contributed two truckloads of medicines and medical supplies, which were turned back by the Hamas authorities.

Funding

At the start of the demonstrations, the Health Cluster appealed for $4.5 million to cover the immediate needs for drugs and disposables, of which $1.8 million were provided by the OPT Humanitarian Fund, and $1.26 million by the UN Central Emergency Relief Fund (CERF), leaving a $1.44 million gap. Subsequently, and following the continuation of the demonstrations beyond the initially expected period, as well as the volume and gravity of injuries, the Health Cluster indicated that an additional $19.2 million is urgently needed to cover the needs of the MoH and NGOs in managing trauma and providing essential healthcare until end September 2018. As of end May, $6.3 million have been provided or pledged by various donors, leaving a gap of $12.9 million.

Impact on health staff and facilities

Between 30 March and 31 May, Israeli forces shot and killed one health worker (by a live bullet wound to the upper body), and injured another 245; 40 ambulances sustained damage. Of the total injured health workers, 16 were hit by bullets. In a single day on 14 May, 15 health personnel working with the Palestinian Civil Defence and PRCS field medical teams were injured by bullets or shrapnel. Health workers deployed near the fence in Gaza are normally wearing vests identifying them as such.

Following the killing of the health worker, WHO reiterated its calls for the protection of all health workers and health facilities, and stated that “in the immediate aftermath of a health attack, patients are deprived of potentially life-saving care at the frontline. In the longer term, the cumulative effect of attacks can lead to reduced availability of health care for the population, as well as affecting the longer-term health, including the mental health, of staff”.[5]

In a statement released on 13 May, the Humanitarian Coordinator, Mr. Jamie MacGoldrick, said that “It is inconceivable that first responders lack protective gear and must risk their own lives in order to provide first aid to the injured. Health workers must be protected at all times and the right to health respected.”

Latest development: On 1 June, during the Gaza demonstrations at the perimeter fence, Israeli forces shot with live ammunition and killed a 21-year-old Palestinian female, volunteering with the Palestinian Medical Relief Society (PMRS), while on duty

Access for the injured to healthcare outside Gaza

Patients referred for medical treatment outside Gaza, especially those injured in the latest demonstrations, face major access constraints. To reach hospitals in the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, Israel or Jordan, patients must leave Gaza through the Erez Crossing with Israel, which requires them to obtain an exit permit from the Israeli authorities. As of 20 May, 40 patients injured in the demonstrations have applied for such permits, of whom one-third (13 patients) had their applications approved, over half (21 patients) were rejected, and the rest were still pending, compared to a 60 per cent approval rate for the first quarter of 2018. One of the patients denied exit subsequently died of his wounds at the Gaza European hospital.

Access to hospitals in Egypt has been also highly constrained due to the limited and erratic opening of the Rafah crossing for the past three years. However, the Egyptian authorities announced the continuous opening of the crossing for the whole month of Ramadan, which started on 17 May, the longest such opening since 2014. From 30 March to 26 May, a total of nine Palestinians injured during demonstrations exited via Rafah to Egypt, and ten injured during the demonstrations were turned back at the border crossing. Jordan coordinated the direct evacuation of an additional 30 injured patients through Israel to Jordan, as of 23 May: Seven were evacuated on 20 May and the rest on 23 May.

Uniformed Paramedic shot while trying to assist injured

Thirty-three-year-old paramedic and father of two, Yousef Abu Muamer, has been working with the PRCS since he was 23 years old. On 5 May, he was shot by Israeli forces, while in his PRCS uniform, during an attempt to assist an injured person. It is now unclear if he will fully recover, and how he will support his family in the meantime.

Abu Muamer was tasked with responding to medical needs in the middle area near the perimeter fence with Israel. At midday on 5 May, he received a call from the PRCS operations room requesting him to respond to an injury reported east of Deir El-Balah.

“With a colleague, I went to the location 300 meters from the perimeter fence. No one was there except us and the man who was shot in his foot with live ammunition. We provided him with first aid and lifted him onto the stretcher. As we picked up the stretcher and were about to move, I was shot by an Israeli sniper in my right knee.

The shots at us continued as I dragged myself towards the ambulance. All I could think about was what my two kids’ lives would be like if I died. When we got behind the ambulance, my colleague gave me first aid, and then called in for support.

My knee nerve is badly torn. The bullet did not exit and I still have shrapnel in my leg. Now I can’t bend my leg or walk without crutches.

I really don’t know how this all happened. It was midday, the PRCS logo on the ambulance is clear, and both my colleague and I were wearing the highly visible PRCS uniform. It was clear that we are medics, yet this didn’t save us from being targeted.”

No safe space: impact of repeated and significant exposure to tear gas

Tear gas inhalation requiring medical intervention has been the most frequent type of injury in clashes between Palestinians and Israeli forces in recent years. Since the start of the mass demonstrations in Gaza and up to 19 May, a total of 5,572 people were treated for tear gas inhalation, of whom over 1,300 were hospitalized. Although the least lethal of all crowd control means used by Israeli forces, prolonged repeated exposure to tear gas could result in significant health and psychosocial impact.

Concerned over repeated and large amounts of tear gas used by Israeli forces in several West Bank refugee camps, UNRWA commissioned medical experts from the University of California, Berkeley, to carry out a preliminary assessment of the health impact of such exposure in Aida and Dheisheh camps in Bethlehem. The report that followed was entitled “No Safe Space” and was published in December 2017.

In a household survey of Aida camp, 100 per cent of refugees reported that they had been exposed to tear gas in the past year; 84 per cent had been exposed in their homes in the camp; 55 per cent had been exposed between three and 10 times in the month preceding the survey, both indoors and outdoors (homes, schools, offices). Overall, camp residents described their inability to prevent and/or mitigate their exposure to tear gas or its health effects. For them there were no safe places in the camps.

Significant acute health impacts linked to tear gas exposure were reported: Over 75 per cent of respondents had symptoms lasting longer than 24 hours, including eye-related complaints, respiratory problems, skin irritation and pain. More than 20 per cent of the respondents had ongoing symptoms: headaches, eye irritation, sweating and difficulty breathing.

The repeated and continuous exposure to tear gas was also linked to very high levels of psychological distress in the camps. The frequency, unpredictability, and seemingly random nature of the raids created a perpetual state of hyper-arousal, fear and worry. This “learned-helplessness” can result in the development of chronic health conditions and overall poor health.

[1] Agencies with ambulances/paramedics and first responders – PRCS; MOH; Civil Defence; Military Medical Services; Palestinian Medical Relief Society (PMRS); Union of Health Work Committees.

[2] MSF, Press release, 19 April 2018.

[3] MoH, “Detailed Casualty Statistics”, Press release, 20 May 2018; data provided by Salama Society to WHO, 23.5.2018.

[4] The Central Drug Store in Gaza is responsible for supplies to all MoH hospitals, which account for approximately two-thirds of hospital capacity in Gaza

[5] WHO, Press statement, 14 May 2018.