Humanitarian Impact of settlements in palestinian neighbourhoods of East Jerusalem: the coercive environment

In recent decades, Israeli settler organizations, with the support of the Israeli authorities, have taken control of properties within Palestinian neighbourhoods in East Jerusalem and established settlement compounds.[1] These settlements are concentrated in the so-called ‘Holy Basin’ area: the Muslim and Christian quarters of the Old City, Silwan, Sheikh Jarrah, At-Tur (Mount of Olives), Wadi Joz, Ras al-Amud and Jabal Mukabbir. Most of these cases were challenged unsuccessfully in Israeli courts. Settlements are illegal under international law.

The establishment of many of these settlement compounds has involved the forcible eviction and displacement of Palestinian residents, with negative humanitarian impact.[2] It has also generated a coercive environment on the daily lives of Palestinians residing in the vicinity of these compounds by creating pressure on them to leave. The main elements of this environment include increased tension, violence and arrests; restrictions on movement and access, particularly during Jewish holidays; and a reduction on privacy due to the presence of private security guards and surveillance cameras.

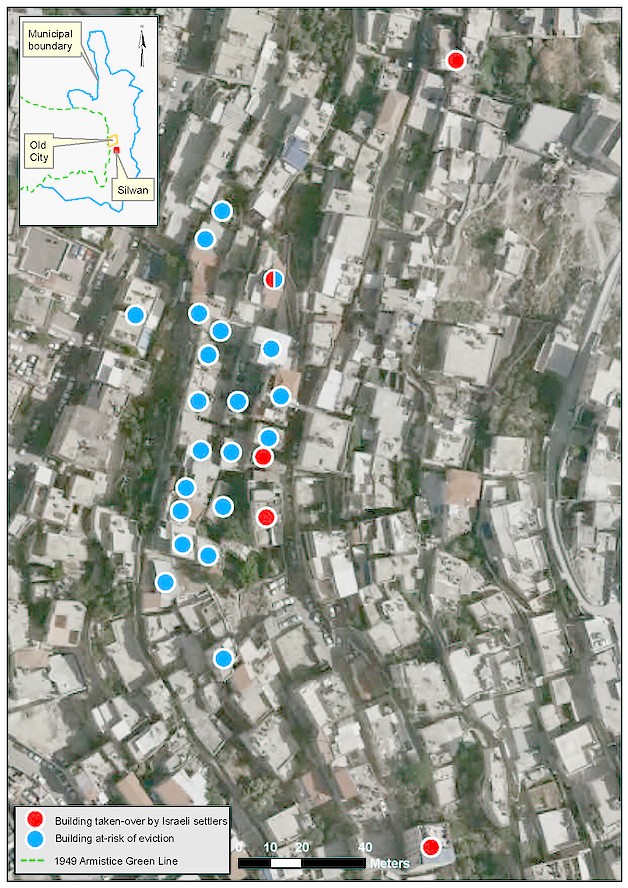

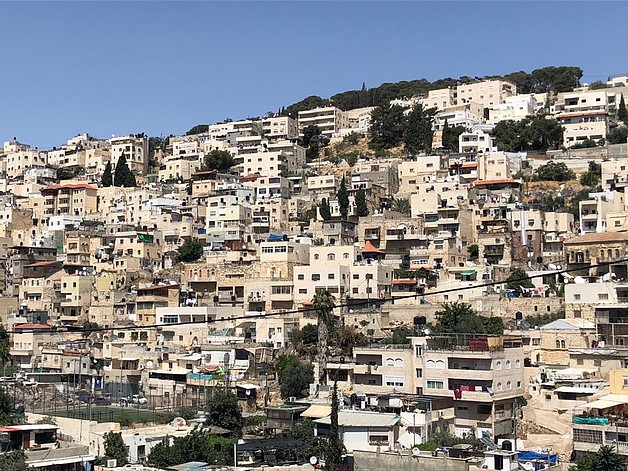

One of the neighbourhoods most under pressure is the densely-populated Batan al Hawa area of Silwan.[3] In 2002, the Israeli Ministry of Justice (the General Custodian office) transferred approximately five dunums of land in Batan al Hawa to the Benvenisti Trust, whose trustees included members of the Ateret Cohanim settler organization. A petition against the transfer of the land was filed in 2017 at the Israeli HCJ by a number of Palestinian families from Batan al Hawa and the ruling is still pending.[4] Since 2002 Ateret Cohanim has filed eviction cases against 21 buildings housing approximately 85 Palestinian families, placing close to 400 people at risk of displacement. Ateret Cohanim now controls a total of six buildings in the area, where 200 Israeli settlers live in close proximity to 700 Palestinians.

Settlement Expansion in Batan Al Hawa neighbouhood, East Jerusalem

House arrests, child detention and restraining orders

According to local residents of Batan al Hawa, the presence of settlers, and their private security guards and Israeli border police, magnifies the potential for tension and violence. On a daily level, this is expressed in movement restrictions, search operations and the detention of local Palestinian residents. Members of the community estimate that there is at least one search operation of local Palestinian homes by Israeli forces each week on the grounds of removing Palestinian flags, confiscating cameras or carrying out arrests, often causing damage to furniture and personal belongings.[5]

Incidents typically involve Palestinian children, often in minor incidents.[6] On at least seven occasions during the recent month of Ramadan, border police and settlers confronted young Palestinians engaged in the traditional custom of drumming to awaken those fasting for their pre-dawn meal. The border police also informed children that toy guns given during the Eid al Fitr holiday were forbidden. In general, there is a strong correlation between high rates of child detention and areas with a strong Israeli settler presence in Palestinian residential areas of East Jerusalem, particularly Silwan and the Old City. Since 2012 UNOCHA has documented more than 560 cases of child detention in Silwan, including Batan al Hawa. This figure makes up close to a quarter of the approximately 2,400 documented cases of children detained during this period.

There are also allegations of double standards whereby settlers park illegally or block roads for extended periods, while Palestinians are fined for minor traffic or parking violations, reportedly at the instigation of settlers. Settlers are also accused by local residents of acting as self-appointed police or municipal inspectors and demanding, for example, that the tax records of local shops be investigated, or photographing unlicensed construction and filing demolition cases against structures by local Palestinians.

According to the Batan al Hawa local committee, since the beginning of 2018 there have been around 40 cases of police orders placing local Palestinians under house arrest or banning them from the locality for varying periods: all but three cases involved boys under 18 years of age. During the same period, one Israeli settler was ordered to stay away from Batan al Hawa for 25 days.[7] The local committee also reported that prior to 2014, tear gas canisters were regularly fired by Israeli forces in clashes with Palestinians, but sound grenades are now used instead following complaints by Israeli settler families in the area.

Coercive environment and population movement

The coercive environment generated by settlement-related violence and restrictions, and concern over the safety of children, has pushed some residents to move to other areas of East Jerusalem. The local committee estimates that at least 30 households moved from Batan al Hawa in 2017 and another seven have left since the beginning of 2018. Many of the families at risk of eviction are Palestine refugees who fear that they may be forcibly displaced once again. In the words of one local Palestinian resident: “Batan al Hawa is a volcano waiting to explode … Settlers are people who move in by force, not to become good neighbours but to take over our homes. Our home for generations has become a battleground with high levels of hostility and stress.”

[1] For further background on the methods used for taking control of properties, see OCHA Humanitarian Bulletin, May 2018, p. 12.

[2] For further information on this impact see OCHA, Ibid. The total number of cases since 1967 is unknown. A survey carried out by OCHA in 2016 indicated that 180 Palestinian households in East Jerusalem had eviction cases filed against them, the majority initiated by settler organizations. As a result, 818 Palestinians, including 372 children, were at risk of displacement. Since then, four of these households, comprising 30 people, have been evicted from their homes.

[3] See ‘Rising tensions following settlement expansion expansion in Palestinian neighbourhoods of East Jerusalem’, OCHA Humanitarian Bulletin, September 2015. ‘Continued settlement activity in East Jerusalem’, OCHA Humanitarian Bulletin, September 2014.

[4] On 14 June 2018, the HCJ ordered the General Custodian to submit a written clarification within 30 days regarding whether they had informed the families of their intention to transfer the land ownership to Ateret Cohanim in 2002; and the community’s lawyers to inform the court about whether the families they represented had received proper notices from the General Custodian prior to the trust deed being issued to Ateret Cohanim. See Nir Hasson, “Israel Must Explain How East Jerusalem Land Was Transferred to Right-wing NGO, Top Court Rules,” Haaretz, 19 June 2018.

[5] OCHA interview with local residents, 21 June 2018.

[6] On 14 February 2018, a settler summoned the border police, alleging that local Palestinian children had tried to run over his children with their bicycle. When the police investigated, obtaining video footage from local cameras, it transpired that the son of the settler had actually jumped in front of the bicycle.

[7] According to area residents, the settler did not comply with the police order and was caught on camera walking in Silwan on 12 March, two days following the order.