Increase in settler violence during the first half of 2017

Despite preventive measures by the Israeli authorities concerns remain about lack of accountability

Settler violence and poor law enforcement by the Israeli authorities have been longstanding concerns. They have undermined the physical security and agricultural livelihoods of tens of thousands of Palestinians in some areas of the West Bank and generated the need for assistance and protection by humanitarian actors, especially for vulnerable groups such as children and women. Humanitarian interventions coordinated by the Protection Cluster include the deployment of a protective presence in high-risk areas; psychosocial support to victims; the installation of protective infrastructure (see case study); the documentation of cases and advocacy; and legal counselling.

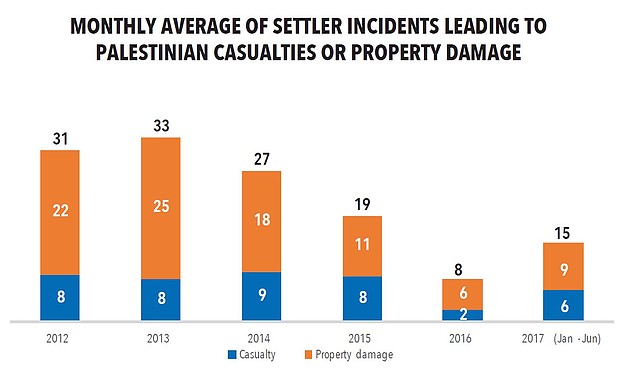

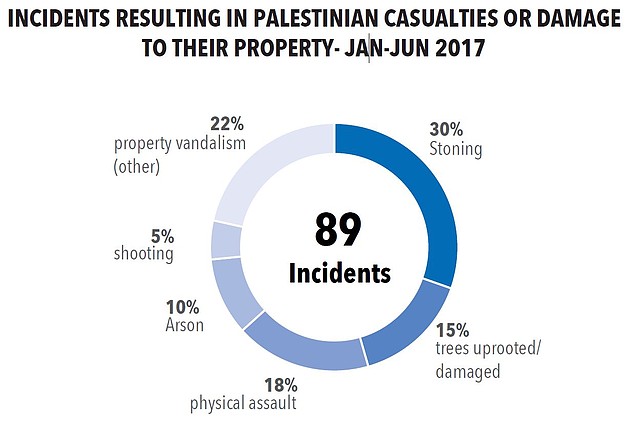

After a three-year decline, settler violence has been on the rise during the first half of 2017. During this period, OCHA documented 89 incidents attributed to Israeli settlers resulting in Palestinian casualties (33 incidents) or in damage to Palestinian property (56 incidents).[2] On a monthly average, this represents an increase of 88 per cent compared with 2016. These incidents led to three Palestinian fatalities[3] and 48 Palestinian injuries, including seven children, as well as damage to over 2,700 trees and 52 vehicles, amongst other consequences.

These figures exclude incidents involving threat and intimidation, trespass on private property or access restrictions imposed by Israeli settlers which did not result in casualties or damage. Although such incidents are more frequent, they are difficult to monitor systematically.

This trend has also been noted by the Israeli Security Agency (ISA or Shabak), which, according to Israeli media reports, has been calling on the government to adopt urgent measures to prevent further deterioration.[4]

The increase in settler violence against Palestinians occurred alongside a major rise in Palestinian attacks against Israelis. During the first half of 2017, OCHA recorded 172 incidents resulting in injuries or damage to property of Israeli settlers. On a monthly average, this constitutes a more than three-fold increase compared with 2016 (112 incidents).[5] Some 95 per cent of these incidents consisted of stone-throwing at vehicles travelling in the West Bank, and the remainder involved the throwing of Molotov cocktails and shootings (four incidents each). As a result, 49 Israeli settlers were injured and dozens of cars were damaged.

Some of the attacks by settlers during this period were reportedly carried out “in response” to the Israeli authorities’ forcible evacuation of the Amona settlement in February 2017.[6] This followed a protracted legal battle that ended in an Israeli High Court ruling ordering removal of the settlement as it had been established on privately owned Palestinian land.

The main types of incident against Palestinians recorded during the first half of 2017 included stone-throwing at Palestinian homes and travelling vehicles; physical assault; uprooting or damaging trees; setting fire to agricultural property; and other acts of vandalism against property. As in previous years, Nablus governorate accounted for the largest number of incidents (34 per cent), followed by Hebron, Jerusalem and Ramallah. The majority of incidents in the Nablus area took place in the six villages,[7] home to some 20,000 Palestinians, surrounding the settlement of Yitzhar and its adjacent outposts.

For example, on 22 April 2017, groups of armed Israeli settlers from Yitzhar settlement approached the villages of Huwwara and Urif (Nablus) and threw stones at a number of homes and vehicles: in Huwwara, three Palestinians were injured, including a 72-year-old woman who was hospitalized as a result. In Urif, the attack triggered clashes with local residents, following which Israeli soldiers intervened by firing rubber bullets and tear gas canisters at Palestinians. Five Palestinians were injured, one by settlers and four by soldiers, and a house and several vehicles incurred damage.

In the same area, on 18 May, an Israeli settler shot and killed a 21-year-old Palestinian after his vehicle was blocked and stoned by Palestinians holding a demonstration in solidarity with Palestinian prisoners. The incident was followed by a series of settler attacks, including the setting on fire of Palestinian crops and stoning of vehicles.

Prevention and accountability

As the occupying power, Israel has the obligation to protect Palestinian civilians from all acts or threats of violence, including by Israeli settlers, and ensure that attacks are investigated effectively and perpetrators held accountable. The existence of gaps in this regard has been a longstanding concern of the humanitarian community in the OPT.

In a report issued in June 2017, the Israeli Ministry of Justice (MoJ) outlined a series of measures adopted by the Israeli authorities in recent years that have contributed to a reduction in settler violence and higher levels of accountability.[8] These measures include the establishment of the Nationalistic Motivated Crimes Unit (NMCU) within the Judea and Samaria police district in 2013; the use of “restraining orders” against settlers suspected of planning attacks that prohibit entry to the West Bank or detention under administrative orders; and the implementation of special security arrangements in “areas of friction” during the olive harvest period. Recently, the Israeli police arrested a leader of a radical settler group and indicted him for incitement to violence.[9]

In addition to the decline in settler attacks since 2013, according to the MoJ, there has been a gradual increase in the percentage of cases of settler violence leading to the prosecution of suspected perpetrators: from 19 per cent of cases investigated in 2013 to nearly 30 per cent in 2015.[10] However, the MoJ’s figures appear to merge settler attacks against Palestinians and those against Israeli forces, thereby hindering analysis of trends regarding accountability in cases of Palestinian victims.

A recent report by Yesh Din, an Israeli human rights organization that has documented complaints about settler violence filed by Palestinians with the Israeli police since 2005, suggests that there has been no progress in accountability.[11] Only 8 per cent of the investigation files monitored by the organization between 2013 and 2016, which reached a final decision (20 out of 245), led to the prosecution of offenders. The other 92 per cent of investigations were closed, the majority on the grounds of ‘offender unknown’. The rate of indictment during this period is nearly the same as that in 2005 when Yesh Din began tracking this indicator.

“After installing the generator and lights, settlers stopped coming at night”

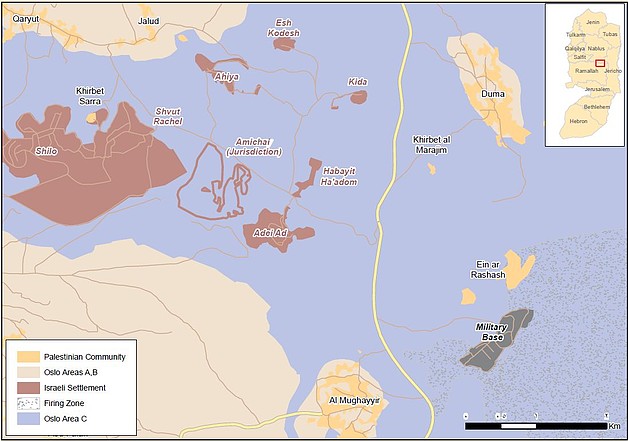

The Ras at Tawil valley (referred to by Israeli settlers as the Shilo valley) between Ramallah and Nablus governorates is a hot spot for settler violence. Since the mid-1990s, this area has been the focus of intensive settlement activities, including the establishment of six unauthorized settlements (outposts), some on privately owned Palestinian land with the informal support of the Israeli authorities.[12] While the number of settler attacks resulting in casualties or property damage has declined in recent years (see above), Palestinians still face settler harassment that undermines their security and livelihoods. In May 2017, the Israeli military approved the boundaries of an additional settlement (Amichai) to be established in this area, allegedly to relocate settlers removed from Amona settlement. See map.

Ein ar Rashash (population ~90) is located entirely in Area C, partially within an area designated as a “firing zone” for military training to the south-east of the Ras at Tawil valley. It is one of the 46 Bedouin communities in the central West Bank at risk of forcible transfer due to a coercive environment that includes the denial of infrastructure for basic services; the demolition of homes and livelihood structures on the grounds of lack of building permits;[13] military training in the vicinity; and systematic intimidation by Israeli settlers.

Sami,[14] 40 years old, lives in the western hamlet of Ein ar Rashash (also known as Khirbet Jib’it), which is the most exposed to settler violence. “Settlers want to force us to leave”, said Sami. “We are in a continuous struggle with them. They prevent us from reaching our land, steal our sheep, follow our children on their way to school and direct spotlights onto our tents at night while singing and dancing […] Last year I went into debt and had to sell some of my sheep to buy around 120 tons of fodder because settlers prevented us from reaching our water wells or planting barley.”

In August 2016, after conducting an assessment, PUI and other international NGOs working in the West Bank provided the residents of this hamlet with a generator and a lighting system; two water tanks; and a fencing unit for the livestock for each family.

In a follow-up visit in April 2017, Sami’s wife, Fatmeh, highlighted the improvement: “Life is easier with the water tanks at steps away from my tent. Previously, we had to get water from the wells in the field and were subject to settler harassment. Settlers also came at night to our front yard, wandered around, made noise, threw things and intimidated us. We used to hide in our tents to guard our young children until the settlers would leave. Since we got the generator and the lights, the settlers stopped coming at night. The generator also enables us to charge our mobile phones, be connected with others and ask for help if needed.”

* This case study was contributed by PUI

[2] Incidents resulting in both casualties (deaths or injuries) and property damage are classified as “casualty incidents”.

[3] Two of these fatalities were persons shot by settlers during two alleged stabbing and ramming attacks.

[4] Alex Fishman, “Jewish terrorism is rearing its head again”, Ynet news, 14 June 2017.

[5] The source for incidents targeting Israeli settlers is primarily the Israeli media.

[6] Settler attacks against Palestinians and Israeli forces in this context have also been termed “price tag” attacks.

[7] Burin, Urif, Huwwara, Madama, Asira al Qibliye and Ein Abus.

[8] Israeli Ministry of Justice, Israel’s Investigation and Prosecution of Ideologically Motivated Offences against Palestinians in the West Bank, June 2017.

[9] Yotam Berger, “West Bank Rabbi to Stand Trial for Incitement to Violence against Arabs”, Ha’aretz, 14 June 2017.

[10] Israeli Ministry of Justice, Ibid, p. 8.

[11] Yesh Din, Law enforcement on Israeli civilians in the West Bank, Data Sheet, February 2017.

[12] Government support for the establishment of unauthorized settlement outposts was carefully documented by a fact-finding committee appointed by the Government of Israel (also known as the Sasson Committee after its chair Talia Sasson), which published its conclusions in 2005.

[13] On 15 February 2016, the Israeli authorities demolished 43 structures, including ten residences, 25 animal shelters and eight external kitchens.

[14] Names in this case study were changed to protect individuals.