The isolation of Palestinians in the Israeli-controlled area of Hebron city continues

1997-2017: Twenty years since the division of Hebron

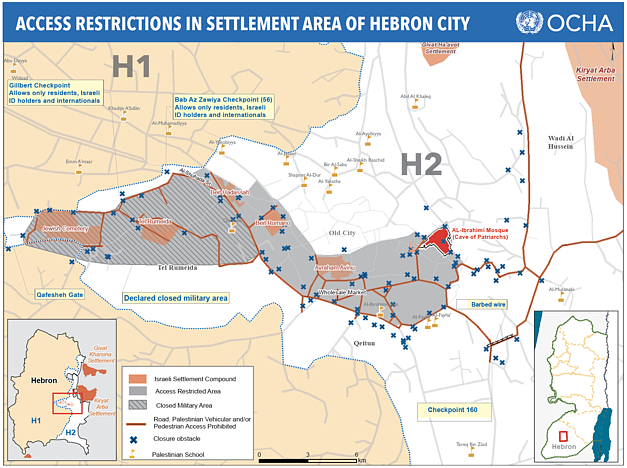

In January 1997, Israel and the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) signed the Protocol Concerning the Redeployment in Hebron. In the agreement, Israel handed over control of 80 per cent of Hebron city (18 km² known as H1) to the Palestinian Authority, while keeping full control over the remaining 20 per cent (known as H2). H2 includes four Israeli settlement compounds, home to a few hundred Israeli settlers and a population of over 40,000 Palestinians.[1]

About 30 per cent of the Palestinians living in the H2 area (approximately 12,000)[2] reside in neighbourhoods adjacent to the settlement compounds and are affected by strict access restrictions. These restrictions have been imposed by the Israeli authorities to protect the settlers, who are exposed to Palestinian violence, and allow them to lead a normal life.

About 30 per cent of the Palestinians living in the H2 area (approximately 12,000)[2] reside in neighbourhoods adjacent to the settlement compounds and are affected by strict access restrictions. These restrictions have been imposed by the Israeli authorities to protect the settlers, who are exposed to Palestinian violence, and allow them to lead a normal life.

Currently, there are over 100 physical obstacles, including 18 permanently-staffed checkpoints and 14 partial checkpoints that separate the settlement area from the rest of the city. Several streets within this area are designated for the exclusive use of settlers, and are access restricted for Palestinian traffic and, in some streets, Palestinian pedestrians are banned.

The coercive environment generated by access restrictions, along with systematic harassment by Israeli settlers, has resulted in the forcible transfer of thousands of Palestinians and the deterioration of the living conditions of those who remain.[3] A recent survey indicates that a third of Palestinian homes in the restricted area (1,105 housing units) are currently abandoned.[4] Over 500 commercial establishments have been shut down by military order and at least 1,100 others have been closed by their owners because of closures and restricted access for customers and suppliers.

Palestinians in Tel Rumeida neighbourhood and Al Shuhada Street at risk of forcible transfer

Since October 2015, the Israeli authorities have further tightened the access restriction regime in the settlement area of Hebron city. The additional restrictions on the movement of Palestinians were imposed in the context of a rise in Palestinian attacks and alleged attacks (mostly stabbing) against Israeli forces and settlers in the city, which resulted in the killing of one Israeli and 25 Palestinian suspected perpetrators.

Since November 2015, Tel Rumeida neighborhood and Al Shuhada Street, where approximately 2,000 Palestinians live, have been declared a closed military area. Only Palestinian residents of the two areas who were registered with the army and allocated a number hand written on the cover of their IDs[5] are allowed through the two checkpoints (Bab Az Zawiya and Gilbert) which control access to their homes.[6] One of these checkpoints (checkpoint 56 or Bab Az Zawiya), located on the main access point to this area from H1, was turned into a multilayered “fortress” with high metal fences and doors, automated metal turnstiles, metal detectors and a military lookout point. During religious celebrations by Israeli settlers and their visitors, the area is hermetically sealed off to Palestinians, leaving some locked in their homes and others unable to return home on time.[7]

The numbering system and the entrenchment of the checkpoint infrastructure have had a severe impact on the living conditions of Palestinians, further isolating residents and separating families. People who had moved out of the area before the numbering system was introduced, can no longer visit their families, neither can relatives or friends who live outside the two areas. Children’s friendship circles and marriage opportunities have become limited. Over the past year, some families left the area so that their daughters could marry and so did young men whose future parents-in-law refused to allow their daughters to move to an isolated area: in Palestinian society, the bride traditionally follows her husband.

The provision of emergency services such as ambulances remains the same as before October 2015. However, delays are inevitable due to the coordination system in place, which requires the Palestinian Red Crescent Society (PRCS) to coordinate with the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), which in turn coordinates with the Israeli District Coordination Liaison office (DCL).[8] To reduce the risk of delayed arrival of fire brigades, an international organization has supplied residents with fire extinguishers.[9]

Access to other services has also been affected. “The sewage cesspit in my house has been overflowing for three years, but I have not been able to bring in pumping machines, and the municipality has been unable to connect us to the sewage network,” a Tel Rumeida resident reported. There are at least 15 households in the area which are also not connected to the sewage network. According to the Hebron Municipality, the Israeli authorities have agreed in principle to connect households to the sewage network but are still restricting the entry of workers and machinery, citing logistical reasons.

As was the case prior to the imposition of the numbering regime, children from Tel Rumeida and Al Shuhada Street are forced to use detours to reach their schools, which are also in the H2 area. “Twice a day I have to go through Bab Az Zawiya checkpoint to reach my school and return home again. It takes me longer than it would if Al Shuhada Street was open to us. During Jewish holidays and when the security situation is tense, I also get searched at the checkpoint. Soldiers ask me to empty my bag and show them the books I have,” a 13-year-old girl from Tel Rumeida explained.

Due to the revolving doors and metal detectors installed at Bab Az Zawiya and Gilbert checkpoints,[10] large items such as electric appliances or furniture are only permitted through a normally-closed gate (Qafesheh), about two kilometres away from the Bab Az Zawiya-end of Al Shuhada Street. The entry of such items requires prior coordination with the DCL. As Palestinians are not allowed to drive their cars inside the area, the items have to be transferred on small carts.

Access restrictions to the Ibrahimi Mosque/Cave of the Patriarchs area have also been tightened since October 2015. Although the sweeping ban on the entry of all Palestinians aged 16-30 was lifted during the second half of 2016, those in this age group are still frequently denied access, especially on Fridays, Saturdays and during Jewish holidays.

A family torn apart: the case of Jamila al Shalaldih

The house of Jamila al Shalaldih in Al Shuhada Street is sandwiched between two checkpoints: Bab Az Zawiya and 55. Its once open-aired and naturally-lit patio is covered with a metal safety net ceiling, installed in 2005 to protect Jamila and her family from settlers throwing stones and rubbish at them. The southern side of the patio borders the Tel Rumeida Palestinian kindergarten, inaugurated in 2015, and a site of regular settler harassment. Before the kindergarten was opened, Jamila said settlers used to come and sit on the wall to harass her and her family, forcing the family to extend the wall vertically to stop this activity.

Jamila, aged 55, has been living in Al Shuhada Street for thirty years and has been detained in Israeli jails 25 times for confronting settlers and soldiers. She spoke of her experience of settler harassment and violence, and military closures.

Jamila, aged 55, has been living in Al Shuhada Street for thirty years and has been detained in Israeli jails 25 times for confronting settlers and soldiers. She spoke of her experience of settler harassment and violence, and military closures.

“I have not left the house for over a month now. I am a sick woman with asthma and can no longer take the humiliation of soldiers or checkpoints: the scanning, the searches and the delays.[11] I’ve even stopped going to see the doctor. I’ve stopped taking medication and only use the inhaler which my son bought for me. Since October 2015, none of my family members, who all live outside the old city, can visit me. During the Eid (Muslim holiday) we made cookies and prepared ourselves, but no one was allowed in. I only get to see my neighbour and recently some internationals came to show their solidarity. I often stay at home for days without seeing anyone but walls. I cannot even look upwards to see the sky without being reminded of settler harassment.

The neighbourhood is almost empty of people. About 80 families left during the second intifada. I was among the very few, one or two households, who remained. I paid a high price for that. My husband divorced me in 2006 because I refused to move out after soldiers unleashed their dogs to attack him. His tailoring business, which is just outside the house, was also shut down. He had four shops, now all closed. I stayed here with my son and two daughters, who are married now. One of my daughters just got married two months ago. A few months earlier when she was coming home from college, I received a phone call from her telling me that the soldier at Bab Az Zawiya checkpoint was asking her to take off her jilbab (a long and loose-fit clothing) as it kept buzzing every time she passed through the metal detection barrier. I dashed to the checkpoint. I blocked the road and did not let settlers pass. I demanded that the army officer get there and reprimand the soldier. After the incident, my daughter became ill and depressed. Life in Al Shuhada Street is a nightmare. There is no humanity. There is no accountability. We’re at the whim of the settlers and soldiers,” said Jamila.

Imad Abu Shamsiyyi: Living in a cage and feeling like a prisoner

Imad is a resident of Tel Rumeida and an activist with Human Rights Defenders, documenting human rights violations with his video camera. He is married and has five children. Imad’s house located between Bab Az Zawiya and Gilbert checkpoints, each a two minute walk from his house. On 24 March 2016, Imad filmed the killing by an Israeli soldier of Abed al-Fatah Al Shareef, an incapacitated Palestinian assailant who had already been shot and injured after stabbing a soldier at Gilbert checkpoint. On 21 February

2017, the soldier was convicted of manslaughter for shooting dead Al Shareef and was sentenced to one and a half years’ imprisonment.[12]

Reaching Imad’s house was like entering a cage. The main entrance to the house is blocked by a concrete wall made of slabs, erected during the second intifada and running for about 50 metres with only one opening that is about a metre wide. The Gilbert-checkpoint end of the wall has a military watch tower which was put in place after the filming of the Al Shareef incident. Across the road, a CCTV camera faces Imad’s house; this camera was also introduced after the March 2016 incident. The house itself is surrounded by metal net fences and the outdoor patio has a net ceiling that was introduced following intense settler attacks, including the throwing of firebombs and large stones. Imad spoke of the ordeal of life under closures.

“Since filming the extra-judicial killing of Al Shareef, life has been unsafe and the family has been torn apart. We’ve been subject to settler violence and threats, as well as harassment from the army. For four months, the army, citing safety reasons, prevented us from using the main entrance to enter or exit the house. Molotov firebombs were thrown at my house and we had to sleep outside of the city for a few nights. Fearing for my older sons’ lives, I had to send them to Al ‘Ezarriyih. They’re only 15 and 17 years old.

My daughter got engaged and married recently. Contrary to the local tradition of having the future in-laws come to ask for the daughter’s hand in her parents’ house, we had to do it at a relative’s house in H1. Her wedding also took place outside of our house as relatives and friends, including the groom and his family, do not have the special numbered IDs and cannot pass the checkpoint. Her husband is still unable to visit us for the same reason. “The numbering system” is the same as the Israeli prison system. We’re prisoners with no release date. Closures have put an end to any normal life,” said Imad.

[1] Another settlement compound, an extension of Kiryat Arba settlement, lies on the border of H2 where Palestinian movement is also restricted, especially on Saturdays and during Jewish holidays. Within H2, scattered Palestinian houses have been taken over by settlers.

[2] Figures based on a 2015 survey conducted by the Hebron Rehabilitation Committee.

[3] Report of the UN Secretary-General, Human rights situation in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including East Jerusalem, A/HRC/34/38, para. 28, 16 March 2017.

[4] Hebron Rehabilitation Committee.

[5] Residents below the age of 16 were not registered as they have no IDs, but are allowed to pass through the checkpoints.

[6] Since May 2016, Israeli ID holders and internationals have been allowed access.

[7] On 13 March 2017, OCHA staff tried to visit Al Shuhada Street and Tel Rumeida. Taking the route of the Ibrahimi Mosque, the staff passed through two staffed checkpoints before being stopped and refused entry by Israeli soldiers at a third one, Tnuva checkpoint, all within a two-minute walk. Staff were informed by the soldiers that Al Shuhada Street and Tel Rumeida were declared a closed military zone for the festive Purim celebrations and only Israelis [settlers] and their invitees were allowed to pass.

[8] Since 2012, after three years of negotiations with the Israeli authorities, the PRCS has been allowed to operate an ambulance sub-station in the old city of Hebron.

[9] Fire extinguishers were distributed after setting on fire the house of Dawabsheh family in Duma on 31 July 2015 by settlers which resulted in the death of the mother, the father and their infant son.

[10] Gilbert checkpoint has no metal turnstiles, just a metal detector door.

[11] Checkpoints can be closed at any time without any prior warning to local residents. When OCHA staff visited Hebron on 13 March, they met about eight Palestinians at the checkpoint stationed between the old market and the Ibrahimi Mosque/Cave of the Patriarchs. The men had already been waiting for about one hour and a half for the soldiers to allow them in to go home and they had no idea when the checkpoint would open.

[12] See Gili Cohen, “Hebron Shooter Elor Azaria Sentenced to 1.5 Years for Shooting Wounded Palestinian Attacker,” 21 February 2017 Haretz : http://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/1.767137