Palestinian access from Gaza Strip declined sharply in 2017

The number of Palestinians allowed to move in and out of Gaza declined significantly in 2017 compared with 2016. At the Erez crossing, movement via Israel has been in decline since mid-2016. Palestinian access via Rafah, the Egyptian-controlled crossing, also declined during the year from an already extremely low level. As the internal Palestinian divide escalated, access for medical purposes was also restricted during most of 2017 by the PA Ministry of Health, which delayed or suspended payments for patients referred for medical treatment outside Gaza.

These developments have exacerbated the isolation of Gaza from the remainder of the OPT and the outside world, further limiting access to medical treatment unavailable in Gaza, to higher education, to family and social life, and to employment and economic opportunities as well as impeding the realization of a range of human rights. The movement of national staff employed by the UN and international NGOs was also restricted in 2017 and impeded the running of humanitarian operations.

Following the Palestinian reconciliation agreement signed on 12 October, the Hamas authorities handed over control of the Gaza side of the Erez, Kerem Shalom and Rafah crossings to the Palestinian Authority (PA) on November 1, and dismantled the Hamas-run Arba’ Arba’ checkpoint that controlled access to the Erez crossing. To date, this development has had no apparent impact on the passage of Palestinians from Gaza through the Israeli- and Egyptian-controlled crossings.

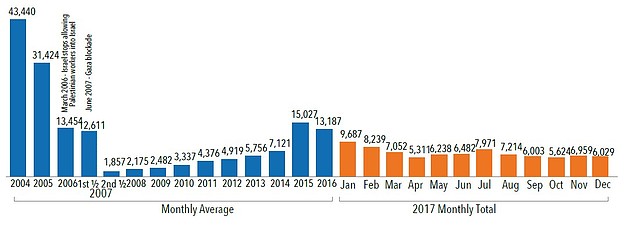

Significant decline in movement through Erez checkpoint

The exit of Palestinians from Gaza through the Israeli-controlled Erez crossing declined by almost 50 per cent in 2017 compared with 2016: on average, there were about 7,000 exits per month (as of 30 November), down from 13,200 exits per month in 2016. Prior to the start of the second Intifada in 2000, there were over half a million exits per month from Gaza, primarily for work in Israel. Work permits for Palestinians from Gaza have since been dramatically reduced and were totally suspended from 2006.

Erez: crossings into Israel

Other restrictions introduced by the Israel authorities in 2017 included additional prohibitions on items carried by Palestinians leaving Gaza via Erez, primarily electronic devices (other than mobile phones), toiletries and food items. In May 2017, the processing time for ‘non-urgent’ permit applications to leave Gaza was extended from 23 to 50-70 working days, not including Fridays, Saturdays or other holidays.

The Erez crossing is vitally important for Palestinian access as it controls the movement of people between Gaza and the West Bank. Under a policy implemented since the beginning of the second Intifada in September 2000, and tightened after June 2007 following the takeover of Gaza by Hamas, only people belonging to specific Israeli-defined categories are eligible for an exit permit, subject to a security check. In recent years, these categories have included patients referred for medical treatment outside Gaza and their companions; traders; staff of international organizations; and exceptional humanitarian cases.

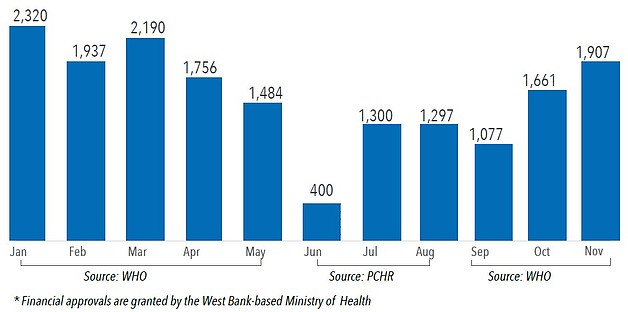

Referral of patients remains highly restricted

By the end of November 2017, the approval rate for permit applications by Palestinian patients to travel via Erez was 54 per cent, down from 62 per cent in 2016. This is the lowest approval rate since 2006 when the World Health Organization (WHO) began monitoring patient access from Gaza. The decline is occurring alongside a gradual increase in the absolute number of referrals and related permit applications to West Bank hospitals in the wake of stricter constraints via the Rafah crossing.

Most unsuccessful applications in 2017 were delayed, meaning that they were not processed in time rather than rejected on security grounds, i.e. no response was received by the date of the hospital appointment, requiring patients to re-schedule the missed appointment and submit another permit application. In situations such as cancer treatment, delays can have life-threatening implications for patient health. According to new Israeli guidelines effective from May 2017, patients are required to submit non-urgent applications at least 20 working days prior to the date of their hospital appointment, doubling the time required previously.

Financial approvals of medical referrals (# of patients)*

Slow processing of requests for financial approval by the Palestinian Ministry of Health in Ramallah also impeded patient referral from Gaza, in the context of a worsening of the internal Palestinian divide. In recent months the number of financial coverage documents issued to patients has increased but has still not reached pre-April 2017 levels.[1]

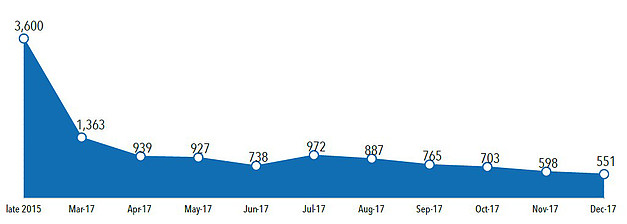

No. of valid permits (businesspeople)

Sharp decrease in permits for businesspeople

This year’s downward trend was particularly pronounced for businesspeople, for whom permit rejections have increased dramatically since mid-2016. According to the Palestinian Civil Affairs Committee, as of December 2017, there were only 551 valid trader permits, a decline of 85 per cent compared with an average of 3,600 permits in late 2015 (see chart).

Many of those now refused entry to Israel are prominent businesspeople in the furniture, garment, food processing, agriculture, tile manufacturing and other industries. These sectors once employed a significant number of workers in the depressed Gaza economy and enjoyed long-standing ties with their counterparts in Israel, the West Bank and internationally. The decade-long blockade, compounded by three devastating escalations of hostilities and the internal Palestinian divide, has eroded coping capacities and this latest setback may force many businesses to shut down entirely.

Deterioration in access by humanitarian staff

Like all Palestinians, national staff employed by the UN or international NGOs must obtain a permit to exit Gaza via Erez. The movement of humanitarian personnel to and from Gaza has been subjected to increased constraints that hamper the ability of staff to properly supervise and coordinate operations and training. In September 2017, the Israeli authorities informed agencies that the processing time for long-term permits will be 55 working days, and 70 for travel abroad. This is a change from the 14 days required at the beginning of 2017, subsequently extended to 26 days before this latest announcement. According to the Israeli authorities, this is part of a stricter vetting process by Israel’s security services. On the other hand, the maximum validity of the security clearance has been extended from six to nine months.

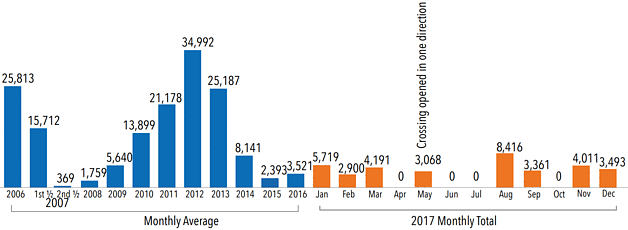

Further decrease in the opening of the Rafah crossing

Until 2013, the Rafah crossing with Egypt was the main crossing point used by Palestinians in Gaza, given the broad restrictions on the Israeli-controlled crossings. Rafah has been largely closed, including for humanitarian assistance, since October 2014, following attacks against Egyptian forces in the Sinai. As with Erez, only specific categories, including patients, students and foreign visa holders, can register on a waiting list held by the authorities in Gaza pending reopening of the crossing. At present, over 20,000 people are registered.

In 2017, the Egyptian-controlled Rafah crossing opened only on exceptional occasions for a total of 36 days compared with 44 days in 2016: 17,000 exits were recorded compared with 26,000 in 2016 and 151,000 in 2013.

In 2017, only 1,222 patients exited via Rafah for medical treatment. Prior to the closure of the crossing in 2014, a monthly average of 4,000 people crossed Rafah for health-related reasons.

Rafah: crossings in both directions

Permit to Israel revoked after 45 years

“My business was one of the best in Gaza but now we barely have enough work to stay open”, explained Ghazi Musht’ha, a pharmacist and the owner of an ice-cream factory. Musht’ha has been working in this industry for more than 45 years. He used to own two ice-cream factories in Gaza City and the former Erez Industrial Zone, which was dismantled by Israel in the 2005 ‘disengagement’.

“For more than 45 years I had almost undisrupted access to Israel and West Bank, and my Israeli exit permit was never denied. I developed very good business relations with my Israeli counterparts and was the Gaza agent for an Israeli medical company for 28 years. Our ice-cream products were very competitive and were even kosher to penetrate the Israeli market, where I used to sell up to 95 per cent of our production.

“In 2016, my permit was denied for security reasons and since then I haven’t been able to travel outside Gaza, although I only used to travel for business and not for personal purposes. In the past, I used to employ up to 120 staff but now I only have 50 to 60 people. They don’t work on a daily basis as our production capacity has been reduced from 20 tons in 2005 to only one. I’ve lost a lot since 2005 and still have debts I am unable to collect from the Israeli agents.

“Electricity is also a huge challenge: this summer we couldn’t produce ice-cream at all. Also, we don’t have adequate access to spare parts, which we used to import from the US. Now we cannot afford spare parts. I tried to import an electricity generator but was not allowed to bring it into Gaza. We consume about eight to 10 thousand litres of diesel per month to compensate for the long power cuts; we don’t have this money but we’re still trying to survive.”

Still waiting at the Rafah crossing

M.N., a 40-year-old mother-of-four, was participating in a sit-in organized at the gate of the Rafah crossing by students, patients, separated spouses and other humanitarian cases to protest against the denial of their right to travel.

In the 2014 hostilities M.N. lost 24 members of her extended family, including her three-year-old child. Her daughter Yasmeen, now 13, was injured and has since developed diabetes with serious complications, including heart dysfunction. “As Yasmeen is regularly admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) and cannot get proper treatment in Gaza, we decided to find her treatment outside the Strip”, M.N. explained.

“Two years ago, we tried to have Yasmeen treated in a West Bank hospital but our permit applications were denied for reasons never explained to us. We then decided to treat Yasmeen aboard and luckily found someone who agreed to help us cover some of the expenses, but the Rafah crossing was always closed.

“We registered at the travellers’ registration office and our names were approved. Unfortunately Yasmeen was admitted to the ICU during this period and we couldn’t leave Gaza. In February 2016 we registered again but our names weren’t approved on the travellers’ list until the last opening of the crossing in November 2017. We were informed that our bus was scheduled to be the first to pass on a specific day, but the evening before, a new list of travellers was approved, although their names weren’t registered at the registration office.

“These people had paid a large amount of money to certain bodies and busloads of them crossed, but our bus didn’t. My husband tried to facilitate our travel through Rafah but he was asked to pay around $3000 for each of us. That’s a large amount of money that we can’t afford. Anyway, I’m not willing to spend the travel expenses we saved on bribes.

It’s such a difficult situation we are facing. It took us up to two years to find a sponsor for Yasmeen and we are so afraid of losing her now.”

[1] WHO monthly reports on referral of patients from the Gaza Strip, October 2017. Link